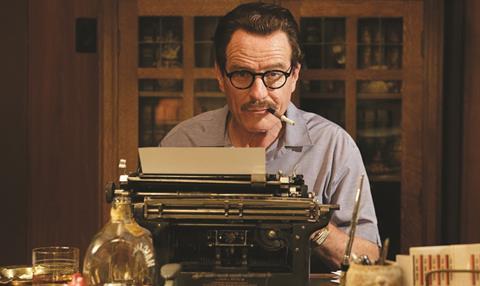

Bryan Cranston, the Oscar and Bafta-nominated star of Trumbo, talks to Jeremy Kay about digging deep to find the truth behind one of Hollywood’s screenwriting greats.

Bryan Cranston did not know much about Dalton Trumbo when he signed on to play the Oscar-winning blacklisted screenwriter. It’s one of the things he loves about acting.

“You say, ‘I need to crack open that guy and see what he was feeling and his sensibility,’” says Cranston, whose performance has earned him both Bafta and Oscar nominations for best actor. “Once you do that, that character speaks inside. As you work on the script, you’re now seeing things through that filter.

“You have to be willing to make a fool of yourself in order to be foolproof.”

“Dalton Trumbo was, like most characters in the non-fictional world, outside me and there’s that trepidation… that possibility that you take on a character and you never crack him and it stays outside you and you’re suddenly chasing that character and never quite comfortable. I felt comfortable.”

It is a morning in early January and Cranston is warming to his subject as he speaks down the phone, despite being up until 1:30am the night before shooting Wakefield, in which he plays a man who experiences a breakdown.

Trumbo went through his own trauma. As one of the so-called ‘Hollywood Ten’, the writers and directors persecuted for their perceived links to the Communist Party in postwar America — Trumbo was a card-carrying member for several years — he was shunned by the studios and hounded by gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (played in the film by Helen Mirren). Trumbo refused to testify in front of the House of

Un-American Activities Committee and was jailed for 11 months on charges of contempt of Congress.

On his release, Trumbo orchestrated a brilliant comeback: he ghost-wrote Roman Holiday (1953) and used a pseudonym for The Brave One (1957). Both won Oscars for Trumbo’s alter-egos and were eventually reinstated to their rightful creator in 1975 for The Brave One, shortly before his death, and posthumously for Roman Holiday in 1993.

He also wrote both Exodus (1960) and Spartacus (1960). On the latter, Kirk Douglas lobbied to have him recognised as the writer and the blacklist era began to fade. Indeed in 1970 he was presented with the lifetime achievement award by the Writers Guild of America (WGA). His acceptance speech was a graceful cheek-turner of Biblical proportions. Trumbo died in 1976.

Inner power

Cranston imbues Trumbo with a formidable inner drive that means he was seldom bowed despite the slings and arrows. Yet Cranston says the pain was visible.

“He was angry and upset that he was being put through this and forced to put his family through it and the uncertainty of it,” he suggests. “When you think of all those kids who are family members of all those blacklisted writers and going to school and being tortured psychologically… a tender mind [would ask], ‘Did I do something wrong?’ It was a brutal time and had a ripple effect that deeply damaged many of the people who were involved.”

“It was a brutal time and had a ripple effect that deeply damaged many of the people who were involved.”

Much of a sequence in Trumbo set at the 1970 WGA ceremony was taken directly from transcripts of the actual event. “He was kind of criticised for that [speech] by his friends and even his wife [Cleo, played by Diane Lane],” says Cranston. “They thought he let his enemies off too easily.

“He had a chance to deliver a death blow with his sabre, which in this case were his words, and he didn’t do it. Trumbo felt everyone had suffered so much he didn’t feel victorious… there was nothing to celebrate here. He didn’t want to make it a celebration.”

Cranston had plenty of access to the facts of Trumbo’s life. But he discovered he had to dig deep for the riches.

“There’s plenty of source material and with someone like Dalton Trumbo there are audio tapes and video tapes and people still alive who knew him — those are very available,” he says. “The question I was getting is, ‘What is it you’re looking for?’ And the answer was, ‘I didn’t know.’ But I do know when something resonates and you have to keep looking. You have to go through a mound of information and it gets distilled to a core of something that’s useable for you.”

Discovering the character

Working with director Jay Roach helped Cranston find the character.

“When you go into a collaboration with a director who you haven’t worked with before, you get a sense of them by your conversations. What I loved about Jay — and we have since made All The Way together, which is coming out in May [Cranston plays Lyndon B Johnson in the HBO drama] — is that in Trumbo we had to trust each other. You open up to the other person to allow them to come in and I am getting a sense of this character [that] he is very theatrical and dynamic. I had to find him.

“From take to take on the same scene, he would experiment and I would do one subtly and one normally or go for it and make a splash because you never know what kind of experience it’s going to be. It could explode the scene and propel it nicely or it could be too big. You have to be willing to make a fool of yourself in order to be foolproof.”

The risks were worth it. Cranston — who has collected a Golden Globe and multiple Emmys for his role as meth cook Walter White in Breaking Bad, and won awards for playing Hal in Malcolm In The Middle — has earned some of the most glowing reviews of his career.

Family secrets

Trumbo’s daughters, Melissa and Nikola, offered insights as Cranston spoke with them to pick up on the small things; the small things that became big things to those who knew the writer, and would either complement the portrayal or stick out like a sore thumb.

“He was addicted to [writing] and maybe was what we could consider someone who was bipolar or had ADHD, perhaps. His daughters were very helpful in finding those nuances,” Cranston reveals.

“There was an earlier iteration of the screenplay that had Dalton take his kids to get ice cream, and his daughters when they read that laughed and said he would never do that. He was irascible, he was dictatorial. He held these meetings [with the family] and said, ‘This is what’s going to happen,’ and the mores of society allowed that to take place.

“His daughters told me they never went on holiday. He was working and would work doggedly, hour after hour after hour.”

It is a character trait that is mirrored by Hopper, the hard-charging Hollywood commentator who would stop at nothing to expose the writer and others for their political affiliations.

“I believe she truly believed that what she was doing was productive in following her ideologies,” suggests Cranston. “But she ended up on the wrong side of history. Hollywood wasn’t the liberal bastion then that it is today. Back then it was split nearly in half so it was very much a bit of a level playing field, where there were conservatives and liberals… there were many members of the community who were conservative. I think it’s a good thing, not a bad thing. In order to be truly engaged in a meaningful conversation and move society forward in a productive way, all voices need to be heard, even someone as bombastic as Hedda Hopper, who could and did break careers.”

No matter what his opponents threw at him, Trumbo persevered and is seen performing his favourite ritual: writing in the bath, typewriter propped up in front of him as he clatters away, pipe in mouth.

“Because of his poor eating habits and drinking and sleeping habits, he would write for hours on end and as a result had chronic back problems,” Cranston explains. “His doctors told him he needed to soak his back in salts in a bath for hours a day. He created an office in a bathtub. His form of exercise was circumnavigating the pool, muttering to himself with the cards and talking as characters, working out scenes.”

No comments yet