Four decades ago, film-making technology embarked on a journey that took it far, far away from the rudimentary techniques of previous eras. John Hazelton tracks the progress of the tech revolution

The Birth of CGI

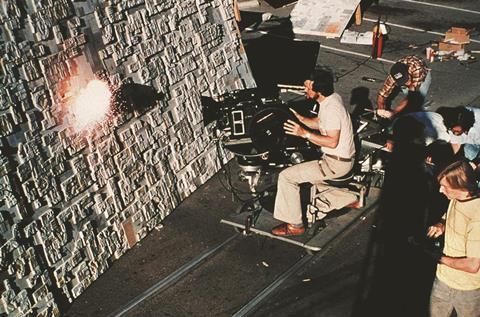

For the visual effects sector, the journey began in 1975 in a warehouse in Van Nuys. It was in that unprepossessing Los Angeles suburb that George Lucas assembled the VFX team which, as Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), would design and implement the effects for 1977’s ground-breaking Star Wars.

Led by John Dykstra, the team used off-the-shelf computer memory and a computer-controlled motion camera system dubbed Dykstraflex to shoot miniature models and create the film’s thrilling space combat sequences.

The success of Star Wars — and, in the same year, of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters Of The Third Kind — started a sci-fi boom which created a huge fresh demand for VFX work. And the development of new computing hardware, as well as software tools such as Alias, AutoDesk and Side Effects, soon led to a rapid advance in VFX capabilities.

The first extensive use of 3D computer-generated imagery (CGI) came in Disney’s 1982 live-action outing Tron. Seven years later, James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989) became — with ILM’s help — the first film to seamlessly integrate photo-realistic CGI into live-action scenes and, just two years after that, Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) gave the world its first partially CG main character.

Employing stop-motion animators working with computer input devices, Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) combined photo-realistic CG dinosaurs — again created by ILM — with life-sized animatronic counterparts. And, in turn, that breakthrough led to the enhanced effects inserted into the original Star Wars trilogy by Lucas when the films were re-released in 1997.

‘The success of Star Wars started a sci-fi boom which created a huge fresh demand for VFX work’

For 1999’s Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace, Lucas and ILM created a ‘digital backlot’ of fantasy backgrounds, sets and vehicles, using digital work in 95% of the frames in the film. They also created a menagerie of all-CG characters, among them the controversial Jar Jar Binks.

Another effects house, New Zealand’s Weta Digital, also made substantial breakthroughs with Peter Jackson’s Lord Of The Rings trilogy — the second instalment of which, 2002’s The Two Towers, employed a real-time motion capture system to turn the performance of actor Andy Serkis into 3D CGI character Gollum.

Weta’s Joe Letteri and his team designed special software for the animation of Gollum’s translucent skin.

CGI reached a milestone with Cameron’s 2009 epic Avatar, the first feature to combine photo-realistic 3D CG characters with a fully CG 3D photo-realistic world.

Working with Weta, Cameron developed an ‘image-based facial performance capture’ system to transform actors’ expressions into those of the blue-skinned Na’vi people, and a ‘virtual camera’ that allowed him to shoot scenes within the film’s CG world.

Over the past half-decade, film-makers have begun to combine advanced VFX technology with more traditional effects techniques.

On 2013’s Gravity, for example, sets, backgrounds and even some costumes were rendered digitally, while actors were also filmed inside a physical ‘light box’ constructed in the studio. And on this year’s Furious 7, motion-capture technology was used to insert co-star Paul Walker’s image into the middle of the physical action after the actor’s untimely death during production.

The VFX evolution may have reached the end of a cycle, however, with this winter’s Star Wars: Episode VII — The Force Awakens. During production, director JJ Abrams reportedly strove to avoid the overuse of CGI and replicate some of the techniques used by Lucas on the original seventies space operas.

Wired for sound

As well as VFX, the original Star Wars also played a role in the development of film sound. With its whooshing spaceships and distinctive lightsaber hum, it helped popularise the then-novel Dolby Stereo format, which ushered in a new generation of film and cinema sound systems.

Two years after Star Wars, film sound took an even more significant step forward with Apocalypse Now (1979), the first film to make extensive use of stereo surround sound.

Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam War epic was mixed and released in a specially developed Dolby Stereo 70mm six-track sound system and, though the system itself was not used extensively thereafter (because use of the 70mm film format waned), it was the precursor of the Dolby 5.1 sound format that soon became an industry standard.

‘Film-makers have begun to combine advanced VFX technology with more traditional effects techniques’

The film also marked the first use, by editor Walter Murch, of the ‘sound designer’ credit.

Film sound went digital in the early nineties and by the middle of the decade several multi-channel digital systems — Dolby’s 5.1-channel Digital Surround, Digital Theater Systems’ 5.1-channel format and Sony Dynamic Digital Sound’s eight-channel system — were in use.

Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace marked the introduction of Dolby Digital Surround EX, a 6.1-channel format that was followed into the marketplace by DTS-ES, another 6.1 system.

More recently, two immersive sound systems — Dolby Atmos (first used on The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012)) and Barco Auro 11.1 (Rise Of The Guardians (2012) was among its early adopters) — have been introduced, both employing additional speakers and software to create sound effects around and above a cinema audience, thus providing film-makers with even more sound design possibilities.

Computer animation

Animated film technology also took a big leap forward in the eighties and has since been converging with VFX technology to the point where, in some instances, the two have become indistinguishable thanks to the increasing use of CGI in both fields.

Though animated features were using limited CGI effects as early as 1985’s The Black Cauldron, computers only began to find a regular place in the animation world in the late eighties, with the development by Disney and Pixar of the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS).

Designed to computerise the ink-and-paint and post-production processes of traditionally animated films, CAPS was employed on projects including Beauty And The Beast (1991), where it allowed hand-drawn material to be combined with CGI footage.

Alongside CAPS, Pixar (formed as part of George Lucas’s empire before being spun off with funding from Apple) was also perfecting its RenderMan rendering software and using it to create acclaimed shorts such as Tin Toy (1988) and Knick Knack (1989). The former eventually formed the basis for 1995’s Toy Story, Pixar’s first full-length film and the first fully CG-animated feature.

Critically acclaimed and a huge box office success (with an eventual worldwide gross of $362m), Toy Story became a model for CG animated features of the next 20 years, from those produced by Pixar itself (among them Finding Nemo (2003), Cars (2006), WALL-E (2008), Up (2009) and last year’s Inside Out), to the outputs of other producers such as DreamWorks Animation, Blue Sky Studios and Illumination Entertainment. Additionally, Pixar’s RenderMan became one of the most widely used software tools in the animation and VFX industries.

The third dimension

Over the past decade Pixar, other animation studios and producers of effects-heavy live-action films have been among the beneficiaries of the revival of interest in 3D film-making.

Originally popularised in the fifties, 3D was revived in the mid-eighties by giant screen cinema company IMAX. With the introduction of digital 3D in the 2000s, the format spread to mainstream films aimed at standard cinemas.

IMAX’s first full-length animated 3D feature was Robert Zemeckis’s 2004 motion-capture project The Polar Express. And in conventional cinemas, digital 3D helped boost the grosses of films including Avatar (2009), Monsters vs Aliens (2009) — on which DreamWorks Animation used a new Intel-developed rendering process called InTru3D — and How To Train Your Dragon (2010).

Though US audiences appear to have tired of 3D recently, the format’s revival is still going strong in the international marketplace, suggesting that it may still have a place in the next 40 years of film technology evolution.

Digital domination

Given his track record as a pioneer in VFX and film sound technology, it’s hardly surprising that George Lucas also had a hand in film-makers’ adoption of digital cinematography.

Though shooting features on video rather than film was promoted by Sony in the late eighties — and first employed in the 1987 feature Julia and Julia — it was Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace that, in 1999, first alerted many film-makers to the new medium. In re-launching his best-known franchise, Lucas achieved a seamless blend of footage produced with high-definition digital video cameras and footage shot on film. And he announced that the upcoming second and third episodes of the franchise would be shot entirely on digital video.

Lucas introduced the medium to fellow director Robert Rodriguez and, in 2001, Rodriguez’s action thriller Once Upon A Time In Mexico became the first widely seen feature to be shot entirely in high-definition digital video. By 2009, Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire had become the first film shot mainly in digital to win the Oscar for best cinematography (as well as best film).

The artistic capabilities of digital video were also amply illustrated in 2002 by director Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark, set in Saint Petersburg’s famous Hermitage museum. To shoot the historical drama in one continuous take, Sokurov and his crew used compact high-definition Sony video cameras mounted on a Steadicam rig (though the digital image was later transferred to a 35mm film negative). Because the camera could only record 46 minutes of footage before requiring a tape change, a prototype hard disk recording system with a special ultra-stable battery was developed for the project, allowing the capture of up to 100 minutes of uncompressed image.

With equipment companies including Alexa, Arri, Canon, Panavision, RED and Sony now producing a wide range of cameras, digital cinematography has allowed film-makers to become more mobile and shoot in locations and styles that would have been impossible with film cameras.

And though some film-makers — notably Christopher Nolan and Quentin Tarantino — still advocate the use of film and film prints, most features made today are both captured and distributed digitally.

No comments yet