Dir/scr: Mimi Chakarova. US. 2011. 73mins

After leaving her native Bulgaria as a young woman in 1990, Chakarova became an investigative photojournalist in the U.S. She had her work cut out for her nearly a decade ago when she began researching this documentary about the sex trafficking of Eastern European women.

Chakarova does shows promise as a filmmaker, and she is nothing if not tenacious.

Not only did she face countless obstacles in her subjects’ countries of origin (Moldova, Ukraine, Russia, Bulgaria, Romania) as well as the foreign climes (Turkey, Dubai, Greece, Israel) where they were flown under false pretences, had their passports confiscated, and shoved into involuntary servitude, she had the adjustment problems of any first-time filmmaker, especially one having to work clandestinely and mostly on her own.

The combination makes The Price of Sex both revelatory and flawed, a well-intended but sometimes frustrating project that does take an important step toward exposing one of the most egregious effects of the free market after 1989 in many of the Communist nations of the former Soviet bloc.

The nearly unbelievable subject matter is of such interest, though, especially because it is set in a netherworld most survivors refuse to talk about—they feel shame and/or accept hush money for their silence—that viewers have already been, and will continue to be, engaged. Chakarova’s access to these victims on camera is nearly unprecedented. Television is the right place for such fare, especially because she stretches the material, even though the final running time is only 73 minutes. Some of the sequences, especially those showing the process of pulling the film together, feel like filler.

The Price of Sex is two films in one: reportage about a highly organized network with tentacles stretching into government and the police; and a sometimes self-congratulatory “making-of” movie that occasionally threatens to overshadow the ostensible topic. Chakarova goes undercover as a prostitute with a hidden camera for one evening in Istanbul, and ventures there again on a last-minute search for pimps and clients to talk to, but there is little payoff in both cases. She wants us to know everything she tried, successful or not.

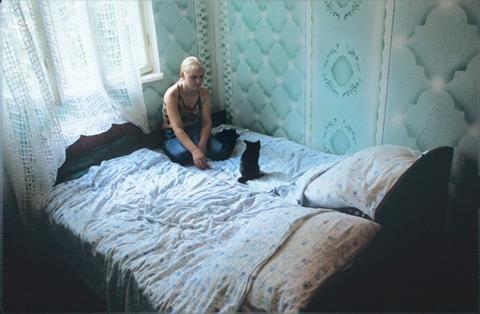

Having grown up in Bulgaria under Communism (“we shared poverty equally”) provides a useful perspective from which she can comment with authority on the harmful effects of the abrupt social and economic transition. She shows recent footage of her birth village, no young people in sight (they have all left seeking better opportunity), in fact, depressingly empty except for the elderly, and juxtaposes it with old home movies from her youth depicting a vibrant milieu. (An excellent soundtrack comprised of harmonious Eastern European chorale music cleverly highlights the rupture in tradition.) Her background also helps her establish rapport with the interviewees.

The UN estimates that one-and-a-half million women have been trafficked from Eastern Europe since the Berlin Wall came down. Most are in the age group 18-24 and from poor, rural, no-hope areas with few jobs. Many have children back home, and a high percentage have alcoholic parents (one advocate for the women says these are more vulnerable). Much of the recruitment is by people they know, most of them, sadly enough, other women.

They are told they will be working as waitresses or cleaners for what is to them a bundle of money, lied to about their destinations, and, upon arrival, immediately forced into prostitution, their “breaking-in” period commencing with their pimps or building labourers as a $3 treat (especially in Dubai). The women are sold frequently and in such perpetual debt to their pimps, it is nearly impossible for them to work it off. To keep them from escaping, most are kept locked up, almost never going outdoors. Some say they had as many as 50 clients a day.

Experts she speaks to say that as long as corruption, economic disparity, and unequal access to justice are the norm, the practice will persist. (Only one government official, in Greece, agreed to talk to her. The others who cooperated are from NGOs and advocacy groups.) The traffickers have developed specialized “cells,” similar to those in terrorist organizations, so that if a member of one cell is arrested, he or she would have no knowledge of the rest of the outfit. How can sincere but token bandages like hotlines compete with such a sophisticated web of criminals?

The most affecting of the interviewees is a Moldavian woman who lives with her mother and son in the country. Unlike others from her village who took money from their pimps in exchange for keeping their mouths shut, she bravely opens up to expose the perpetrators publicly, no matter the familial and societal stigma.

Although the visuals are fine, much of the material in the urban areas necessarily handheld (flashy lights in the red-light and club districts at night threaten to mask the existence of seedy, mostly unshot, interiors), Chakarova’s voiceover is dull and, as far as information goes, banal. (Oddly. AIDS is barely mentioned, even though the women say that most of their clients refused to wear condoms.)

Whether from what she tells us or what she gleans from those she talks to, not a lot of insight on sex trafficking emerges that an informed reader or news watcher would not already be at least superficially familiar with. (As nightmarish as their hell has been, the women recount for the most part versions of the same, horrid, unembellished story.)

Chakarova does shows promise as a filmmaker, and she is nothing if not tenacious. Continued awareness of this contemporary scourge has to be maintained. Perhaps a sequel with more teeth and less solipsism might do the trick.

Production companies: Violeu Films, A Moment in Time Productions

International sales: CAT&docs, www.catndocs.com

Executive producer: Stephen Talbot

Producer: Mimi Chakarova

Cinematography: Adam Keker

Editor: Stephanie Challberg

Music: Christopher Hedge

www.thepriceofsex.org