One of the biggest changes of the past four decades has been the supersonic growth of the film franchise, fuelled by international audiences’ insatiable demand for characters rather than actors. Screen examines this billion-dollar business

Bankruptcy, they say, comes gradually and then suddenly. The same dynamic may be observed at the dawning of the era of the franchise picture.

A glance at the films that have reached the number one slot over the past few years reveals a shift that seems both gradual and sudden, from the 1980s, when original stories including Raiders Of The Lost Ark, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Beverly Hills Cop, Back To The Future, Top Gun and Rain Man dominated, to the more pivotal 1990s, when original winners such as Toy Story, Home Alone, Independence Day and Saving Private Ryan were balanced by successful exploitations of existing source material such as Jurassic Park and sequels Terminator 2 and Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace.

Après, le déluge. The first Harry Potter film in 2001 heralded a period in which literary and comic-book exploitations, together with sequels, have dominated the box office, both domestically and globally, to an unprecedented degree.

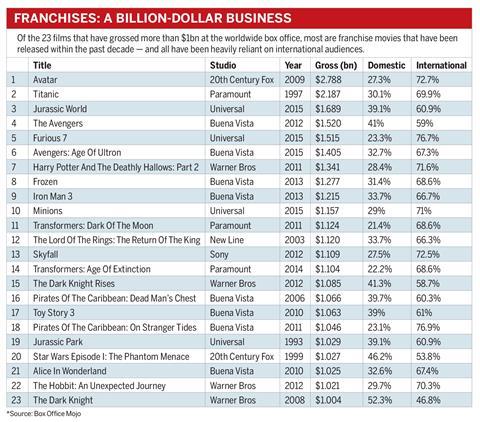

James Cameron’s Avatar — the top US hit of 2009 — has proved a very rare exception indeed. And among the 23 films that have so far earned more than $1bn at the global box office (see table below), only Avatar, Titanic — which certainly had the benefit of high audience familiarity with its eponymous boat — and Frozen might be termed original non-sequel stories, and the latter, inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen, is up for debate.

Warners’ Harry Potter proved a tipping point in more than one way. The Philosopher’s Stone’s arrival in cinemas five weeks before the first episode in New Line’s The Lord Of The Rings trilogy signalled a fresh approach to literary source material, with studios seeking richer recoupment opportunities to reward the investment of bringing characters to life from the page.

“The turning point was 1994. Because that was the first year that international box-office receipts surpassed domestic receipts” - Tim Richards, Vue

Multiple episodes, in other words, became the new goal, although not every attempt — Lemony Snicket, His Dark Materials — was brought to successful sequel fruition. Twilight, in 2008, rebranded the teen flick as Young Adult and unleashed the power of female protagonists, sending hit-hungry producers to the bookshelves.

Viewed through a different lens, the modern era of franchise films began a year earlier than Potter, with Fox and Marvel Enterprises’ X-Men film heralding the rebirth of comic-book exploitations that had distinctly fallen from favour since Joel Schumacher’s creative misfire Batman & Robin in 1997.

Superheroes now occupy such a dominant position in the commercial landscape that it’s easy to forget how gutsy the X-Men greenlight decision was at the time, and ditto Sony’s expensive role of the dice with Sam Raimi and Spider-Man two years later.

In the dawn of the mega-franchise era, Tim Richards, chief executive of 10-territory cinema chain Vue, points to an earlier tipping point that influenced events.

“The turning point was 1994,” he says. “Because that was the first year that international box-office receipts surpassed domestic receipts. That was a wake-up call for everyone that the future really was going to be international and offshore of North America. We’ve seen straight-line growth ever since, and now it’s not uncommon for 70, 80 per cent of receipts for a film to be from international.”

Richards’ early years in exhibition were with companies owned or co-owned by Hollywood studios. “I had met a number of executives with ‘international’ on their business cards that didn’t have passports. International in those days was where executives were parked who didn’t have a future.”

Today, priorities have flipped. Dutch-born Niels Swinkels, executive vice-president of distribution for Universal Pictures International, says: “It’s important to listen and monitor and see what global audiences want rather than be dictated to by American audiences. Most films used to be first and foremost made for the US market. Now, of course, international executives do strongly weigh in on the greenlighting process and influence which films rise to the top of the list.”

Richards adds: “The studios have done a great job in really internationalising their movies, extending their appeal to a broader audience. A good story is something that will be shared in common in different markets in different countries.”

Defining what gives a film international appeal is not so easy. It’s obvious that Transformers, based on the globally popular toy, is a franchise that lends itself to foreign markets, since warring robots are neither dialogue-driven nor culturally specific.

But Harry Potter — filmed in the UK with British actors and set at a British boarding school — owes its appeal not just to broadly relatable themes of teenage self-actualisation, but also the rich specificity of the setting.

The question remains, with Marvel’s ever-expanding universe of characters now facing serious competition from a newly ambitious Warners/DC, whether the superhero-powered Hollywood franchise machine can continue on its current path. Richards sees more good times ahead: “I’m more excited by the business now than I ever have been.”

And he takes encouragement from the tentpole-crowded dating calendar that now runs all the way to 2021, and is also more broadly spaced throughout the year than has historically been the case. “These are films that are, for the most part, named, financed and greenlit. And so I think that really speaks for itself in terms of studios’ commitment to continue to produce great movies, and the fact that they are actually doing that six years out,” he says.

While Universal has mined source material including Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park and Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity to launch hit global properties, one of its biggest ever hits, Furious 7, which earned $1.5bn, is the latest in a film franchise that essentially began with an original screenplay — taking only the broadest inspiration from a 1998 Vibe magazine article. Its reach looks set to expand even further, with Universal recently reporting that it is planning prequels and spin-offs for key characters.

“Luckily,” says Swinkels, “there’s still a lot of room for original films, and original films can also turn into franchises, and that’s what Universal has been particularly successful at over the past couple of years. Roughly, of the 12 franchises that we have live at the moment, six are original. They are not based on a book or a TV show or a comic strip. I think that’s an encouragement but also a testament that we should still endeavour to find original stories.”

For Swinkels, the key is not to do with source material or existing elements or brand-name recognition, but the characters that populate the screen. “Whether it’s a superhero or a character from a comedy, it’s the character people relate to, and want to continue to hang out with,” he says.

Indeed, you only have to look at recent covers of Empire magazine to see that it is characters, not the actors who play them, that are engaging film fans these days; the last time it featured a cover with a star in civilian dress, rather than a character in costume, was in May 2014.

No comments yet