Jerusalem Film Festival is paying tribute to Chantal Akerman with a retrospective of her work. Screen looks back on the pioneering Belgian filmmaker’s career

Some 18 months before her death in the autumn of 2015, pioneering filmmaker Chantal Akerman set down one last time at Jerusalem Film Festival (JFF) in July 2014 with an installation called De La Mer(e) Au Desert.

Filmed during a road trip to the Israeli town of Arad, the immersive experience revolved around tracking shots of desert landscapes projected onto the Jerusalem stone walls of the Mamuta Art and Media Center situated in Hansen House, the former leprosy hospital turned cultural space. A play on the words for ‘mother’ and ‘sea’ in French, its title translated as ‘from the sea (mother) to the desert’.

Footage from the installation would makes its way into Akerman’s final film No Home Movie, capturing her relationship with her mother and muse Natalia Akerman who died in April 2014, as well as the immersive video installation Now, which she exhibited at the 2015 Venice Biennale a few months later.

“At the same time as editing the footage for the installation, we were also watching material Chantal had shot of her mother,” says Akerman’s longtime editor Claire Atherton. “It was a beautiful and emotional time but also sad and difficult.

“Slowly the two sets of images started to intermingle. That is how the film was born.”

Collected works

No Home Movie is one of a dozen films by Akerman screening at JFF this year as part of a retrospective devoted to her work. It has been put together by festival programmer Vivian Ostrovsky with the help of Cinematek, the Royal Belgian Film Archive.

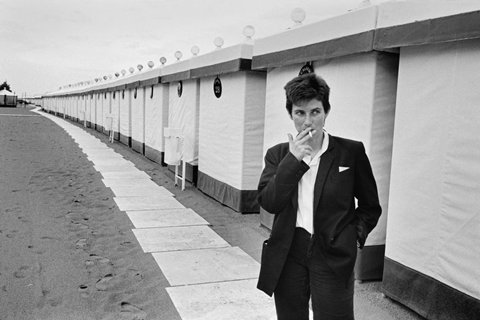

Akerman — who was born and raised in Brussels to Holocaust survivors from Poland but mainly based between Paris and New York — was a regular visitor to Israel and JFF. She first screened here in 1975 with her breakthrough film Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.

The 2014 installation kicked off with an opening night reading by Akerman from her work My Mother Laughs (Ma Mere Rit), devoted to her mother, attended by fans and friends including late festival founder Lia van Leer.

“Chantal came up to me during the event and said, ‘So, when are you going to have my retrospective?’,” recalls Ostrovsky. Her suggestion sowed a seed. “Of course, we were up for it. Many of Chantal’s films had shown at the festival over the years and I had been following her work since the very beginning, even before Jeanne Dielman.”

Ostrovsky first met Akerman when she invited her 1974 feature Je Tu Il Elle to a women’s film festival she organised under the auspices of the Ciné-Femmes International banner in the mid-1970s in Paris.

Akerman directed and starred in the picture as a solitary young woman who embarks on a series of intimate encounters, first with a truck driver, played by a young Niels Arestrup in one of his first big-screen roles, and then an ex-girlfriend. It was regarded as a daring exploration of female sexuality when it hit the festival circuit in the 1970s.

“It was very courageous and a ground-breaker at the time,” Ostrovsky recalls. “After the screening, we got chatting. She asked if I would like to see her very first film Saute Ma Ville (Blow Up My Town).”

Also starring Akerman, this time as a young woman engaged in a series of nonsensical domestic tasks in a sterile apartment that she then blows up, this 1968 debut short remains one of the director’s best-known works.

“I organised a screening in the venue that we used for the festival. We both sat in this huge, empty movie theatre. I loved the film. When we came out, she said, ‘I have quite a presence, don’t I?’” Ostrovsky remembers.

Akerman, she continues, was someone who constantly broke with convention. “She didn’t play by the rules,” says Ostrovsky. “When she was teaching in New York, she would have the students come over to where she was staying because she couldn’t stop smoking and wasn’t allowed to smoke in the classroom. Her students would be lined up in the hall waiting for their tutorials. When she died, lots of these former students turned up to pay tribute at a special memorial event at the Lincoln Center.”

Blow Up My Town will open the retrospective on Friday (July 27) at the heart of a concert event called ‘Chantal?’ created and performed by Akerman’s long-term partner, the cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton, out of her musical response to the film and memories of the filmmaker. The line-up also includes Jeanne Dielman, which put Akerman on the map after it screened to critical acclaim in Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in 1975.

Starring late French actress Delphine Seyrig as a bored housewife going through the motions of a repetitive cooking and cleaning routine, it broke new ground for the way it captured female reality in a domestic setting as well as its observational style and full-frontal framing. It was later cited as an influence by numerous directors including Gus Van Sant on his films Elephant and Last Days.

Rare cuts

Ostrovsky wants to take Jerusalem’s audiences on a journey beyond these well-known Akerman classics. “A lot of people are curious about her work but beyond Jeanne Dielman and Saute Ma Ville, as I’ve discovered myself programming this retrospective, it can be hard to get hold of her other films,” she says.

Further titles in the line-up include Autour De Jeanne Dielman, a making of-style documentary shot alongside the original film. “It’s quite fascinating, especially if you like Jeanne Dielman, and works as a good companion piece to the film,” says Ostrovsky, who has also tracked down a rarely screened TV interview called Chantal Akerman By Chantal Akerman in which the director talks about her work.

The 2006 documentary Down There (La-Bas) — in which Akerman reflects on her Jewish identity and relationship with Israel while holed up in a Tel Aviv apartment — will screen together with the 1972 short self-portrait La Chambre.

“They are both chamber pieces in which she is closed up in a very intimate space but quite different,” says Ostrovsky. “La-Bas is an essay in a documentary style while La Chambre is more experimental and heavily influenced by the structural film scene in the US and artists like Michael Snow.”

Atherton suggests that watching Down There is the best way to understand Akerman’s complicated relationship with Israel. “It is a relationship based on a search for a sense of belonging. Although she was passionate about Israel, she never really felt like she belonged, it was an ‘ailleurs’ [an elsewhere] for her.”

The programme also includes works shot during Akerman’s early years in New York such as the 1977 documentary News From Home, in which images of the city are overlaid with readings from letters sent by her mother back in Brussels. A further joint screening will combine the 1999 documentary South (Sud) — capturing the aftermath of the murder of a black man in the small Texas town of Jasper in 1998 by three white men who dragged him along the road behind their truck — and the short 2007 observational film Nightfall In Shanghai.

“This is the nomadic side of her cinema,” says Ostrovsky. “The way Sud came about was wholly unexpected. Chantal had gone down south to look for locations [for a film inspired by the work of US writer William Faulkner], and came across the story of the murder and set about filming its wake.”

Further titles in the selection include the documentary From The East, a snap-shot of life in Eastern Europe following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1993.

Looking over Akerman’s filmography some two-and-a-half years after her death, one striking aspect of her work is how timely it remains as the world debates issues such as gender equality, immigration, race, belonging and identity.

Atherton attributes this to Akerman’s filmmaking process, which was “hyper-conscious” in terms of how she captured the moment on camera, paying close attention to how it was framed and shot, but never trying to impose meanings, answer questions or fill in gaps in the final work.

“The spectator has to become an active participant in the film, which keeps the material alive,” says Atherton. “You don’t need to come to a Chantal Akerman film with any prior knowledge. You just need to come with an open spirit. Her films take on a different meaning on the basis of who is watching them and when. This is why they remain so relevant today and will still be relevant 50, 100 years from now… they are true classics.”

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

No comments yet