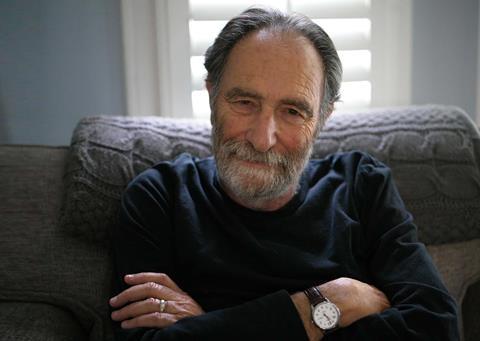

Oscar-winning screenwriter Eric Roth served twin roles on Mank — punching up Jack Fincher’s screenplay and as producer. Mark Salisbury talks to him about his 50-year career, including upcoming films for Denis Villeneuve and Martin Scorsese

Back in the early 1990s, when David Fincher was still best known for his Madonna videos and had yet to direct a feature, he challenged his father Jack, who had recently retired as a Life magazine journalist, to write a screenplay. He even suggested a subject matter: Herman J Mankiewicz, who penned Citizen Kane for Orson Welles, but whose authorship had been controversially overlooked, not least by Welles, until an extended essay in 1971 by the late New Yorker critic Pauline Kael reclaimed it.

Fincher tried in vain to set Mank up for the best part of a decade, but his desire to shoot in black and white proved a sticking point with financiers. Until, that was, Netflix, for whom Fincher had produced House Of Cards and Mindhunters, asked what he wanted to do next. Did he, they wondered, have a passion project he had always wanted to direct? Fincher took down his father’s script from the shelf, and Netflix agreed.

Jack died in 2003 so Fincher called on Eric Roth, with whom he had collaborated on The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button and House Of Cards, to help him finesse the script. “David and I are very close,” says Roth, “and I’ve lent my eye, a point of view, on a few of his other movies. He has a group of us, including Bob Towne, Steven Soderbergh and Spike Jonze, that looks at all of his movies at some point in a cut and you’re allowed to tell him whatever you feel about it. So I’ve been involved in a number of those. He came to me a couple of years ago and asked if I would like to get involved with this.”

Fincher did not want Roth to rewrite his father. Rather, he was interested in his insights into “what it feels like to be a screenwriter, the good and bad things about it. I don’t think Jack knew that world.” What did Roth think of the script? “David didn’t just let me read it, he told me what he thought about it. So I already had a patina of what he thought was working and wasn’t, and I didn’t always agree with him. I thought the script was 85% there. Structurally, it was pretty great. I thought it maybe needed a little more humanity.”

At first, Roth was not even sure he was the best writer to tackle Mank’s period patter and rat-a-tat dialogue which, he admits, is not his forte. “Aaron Sorkin happens to be great at it. He can give you one-line responses that are amazing.” But Fincher was insistent and so Roth signed on. “We would Zoom together every day at 5:30 in the morning and go scene by scene by scene. We might take one line of Jack’s dialogue and make it a little more precise. Even though most of the language was there, we needed to find a way to emphasise certain things or be smart with double-entendres. Jack had provided most of it. We just would enhance it where we could.”

Fincher also drafted Roth in as a producer. “I was a producer on House Of Cards, but I had never produced a movie. I embraced that. I said, ‘Fuck it. I’ll really be a producer.’ And I went every day [to set],” recounts Roth. “David said, ‘What are you doing here?’ And I said, ‘I’m going to sit behind you and bug you.’ I think it was of value. I thought my eyes and ears were good. We fight like cats and dogs. I think he’s worth fighting for, and worth fighting over. That’s how I feel about him.”

Stellar career

Roth has earned his living as a screenwriter for more than 50 years — his first credit being 1970’s To Catch A Pebble — working with everyone from Akira Kurosawa (Rhapsody In August) to Steven Spielberg (Munich) to Michael Mann (The Insider). He won an Oscar in 1995 for Forrest Gump, and has been nominated for his writing another four times (plus once more as a producer of Mank).

“I always wanted to do things with value and to be part of things of value,” he says. “David does, too. We both are interested in our legacies.” But even the most successful screenwriters get rewritten, as Roth did on Munich. The process can be “hurtful” and leave you “heartbroken”, he admits. “You think this is all mine and someone else shares credit with you, or someone comes in and rewrites and you share credit with them.”

A former journalist, drama critic and member of the famous Algonquin Round Table of New York City writers and wits, Mankiewicz believed he was slumming it in Hollywood and didn’t give “a shit” about on-screen credit. Until Citizen Kane, that is. “He wrote on his contract, ‘I don’t want credit.’ Then this [Kane] came along and all of a sudden something mattered. And Welles wanted all the credit. I got that. He knew this was something special and would last longer than he would,” says Roth.

That said, Roth firmly believes directors deserve their “A film by” credit. “A director’s job is not only to put it up on the screen, and help pick out what it looks like and smells like. It requires a good deal of editing and oversight. I’ve turned in 214-page scripts. I have one with Marty [Scorsese] right now, and he’s going to have to cut and reshape some of it. And it will be with me and without me.

“That’s what Orson Welles did,” Roth continues. “I have the full screenplay of Citizen Kane at home, the first draft, which is 332 pages. And there’s not a thing in the movie that’s not in it. Welles had to cut that down to 180 pages and then, finally, 120. That’s a big job. Welles provided the freedom for him to write it, they then did as best they could together. And eventually Welles put his own hands to it, but it was what he’s supposed to do.”

Roth’s next credit will be his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune, directed by Denis Villeneuve for whom he had done some rewriting on Arrival. “I had done a lot of hallucinogenics in my life, and 2001 is probably my favourite movie, and I felt I could do it in a goofy, crazy, maybe not quite Tarkovsky, but interesting way,” says Roth.

But it was too expensive. “Somebody said, ‘What are we going to use to shoot the rest of the movie?’ Denis needed to bring it down and he did.” Eventually, Roth stepped away. “I said, ‘You need to make this a little more grounded because I think people will find it fascinating, but may not be able to relate to a lot of the psychedelic quality.’ So they brought in a very good writer named Jon Spaihts. I have not seen the final movie but I hear it’s incredible.”

Meanwhile, Roth has Killers Of The Flower Moon, based on David Grann’s non-fiction book Killers Of The Flower Moon: The Osage Murders And The Birth Of The FBI, about to start shooting, with Scorsese directing Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro and Jesse Plemons. It is a project that has taken five years and numerous drafts, the most recent being when DiCaprio decided he would rather play the villain than the lead. “Marty called me very late at night and said, ‘Are you laying down or sitting down? Leonardo has a big idea.’ I think Leonardo was right. I’m not sure he can play Gary Cooper, which is what the main character kind of is. It’s a spectacular book. I think it’s going to be the most profound movie about Native Americans that’s ever been made.”

No comments yet