The story behind the rebirth of The Other Side Of The Wind, Orson Welles ‘lost’ film, is enough for a film itself. Producer Filip Jan Rymsza and others take Screen through an extraordinary journey.

It’s almost a decade now since producer Filip Jan Rymsza became aware of Orson Welles’ famous uncompleted film, The Other Side Of The Wind, and realised that the rights were available to it.

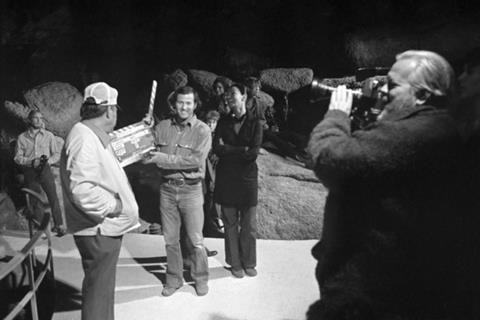

This was the movie starring John Huston as Jake Hannaford, a macho, Hemingway-like movie director trying to revive his career in the “New Hollywood” where he seemed an anachronistic figure. Welles started shooting it in 1970. Rymsza read about in a magazine article about “troubled film productions”.

Rymsza was introduced to Oja Kodar, Welles’ partner and collaborator late in life. This began a long, drawn-out process that has finally led to Welles’ film receiving its world premiere in Venice this week, 48 years after he started shooting it and 33 years after his death in 1985.

Rymsza likens the process of completing the film to “a chess game”: “That was what interested me. Once I started digging, I tried to figure out why nobody was able to finish it. I was slowly introduced to various parties who had undertaken the challenge and had given it up for various reasons. It seemed like in this camp, if you made an enemy, you made an enemy for life. It was tricky to manoeuvre.”

Rymsza decided that whoever controlled the negative would control the film. He was determined to work out the chain of title and to untangle the rights issues, whatever backlash he might face.

The first step was to head to France, where the negative had been locked away under court order. Welles had fallen out with one of his financiers, Mehdi Boushehri, brother-in-law of the shah of Iran. Boushehri wouldn’t allow the material to be distributed until he got his investment back and was keeping the material in Paris.

At the very moment Rymsza finally acquired the rights, the vault where the material was stored went bankrupt and the materials were shipped out to warehouses outside Paris. “Those materials I couldn’t even claim because the company that had taken custody of them was no longer in business,” he says.

Game-changing deal

Serge Toubiana, director of the Cinémathèque Française, helped Rymsza track down the footage and get it out of Paris. There were over 1000 elements, including multiple cans of film and reels of quarter-inch sound.

The producer was well aware of the controversy that had dogged other attempts to complete or reconstruct Welles’ films, including Touch Of Evil (pulled from the Cannes Festival at the last minute), Jess Franco’s ill-starred attempt at finishing Welles’ Don Quixote or the 1992 restoration of Welles’ Othello.

Rymsza, who produced the film alongside Hollywood heavyweight Frank Marshall, started a crowdfunding campaign to pay for the completion of the film before, in September 2016, closing a game-changing deal with Netflix. There are still rights issues to be resolved but this provided the resources to finish the film in the way that Welles intended.

Why did Netflix want to come on board? “Multiple reasons, one being a personal passion for Orson Welles which I share with Ted Sarandos among others. Seeing an opportunity to play some small part in helping this film get finished was personally very satisfying,” says Netflix’s director of content acquisition Ian Bricke.

“Also, looking at it from the broader Netflix perspective, it was something we were certainly capable of doing. We had the scale and reach to help a film like The Other Side Of The Wind to reach its biggest possible audience. There was also something very appealing about a company like ours, somewhat maverick in the broader film business, which feels philosophically in line with Orson Welles.

To use a 21st-century digital distribution platform to help complete and distribute a film from the 1970s that remained unfinished was pretty compelling.”

“[Netflix] were an amazing partner and continue to be. The tricky part of this film was that we needed a distributor to commit to it sight unseen,” Rymsza remembers. “It was a leap of faith for them.”

The filmmakers went to exhaustive efforts to do Welles’ vision justice, bringing in Danny Huston (John Huston’s son) to “lend syllables, just little bits and pieces to support John Huston’s performance” and also working with cutting-edge visual-effects company Industrial Light & Magic.

Oscar-winning editor

Editor Bob Murawski, winner of the new Passion for Film award in Venice this year and an Oscar winner for The Hurt Locker, originally became involved in the project in the early 2000s through his friendship with Welles’ cinematographer, Gary Graver.

“I found out Gary had the work print for The Other Side Of The Wind. He had shot the movie and was trying to get it completed,” Murawski remembers.

Graver died in 2006 and Murawski thought his opportunity to work on the completion of the film was gone. Then, he heard that Rymsza was trying to finish it and offered his services.

“A lot of what we were doing was just trying to find things. We didn’t really have a road map,” Murawski observes of the painstaking editing process. “There were various versions of the script but whenever Orson would shoot, he would deviate from the script pages.

“Much of the job was just figuring out where things would go – finding material that was incredible and trying to figure out where in the context of the movie it went and whether it was even complete.”

The editor was working with filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich (whom Welles had asked to complete the film if anything happened to him) and Frank Marshall, who was a production manager on The Other Side Of The Wind way back when it was shooting. He was also able to draw on the expertise of the critics and historians, Joseph McBride and Jonathan Rosenbaum, two of the pre-eminent experts on Welles’ life and career.

An army of volunteers

Marshall dubbed the small army of critics, filmmakers and cinephiles who’ve worked on the film over the years as “VISTOW: volunteers in the service or Orson Welles.” They didn’t get paid much and often worked very long hours but they all persevered.

Murawski lobbied hard for Michel Legrand, the legendary composer who had scored Welles’ F For Fake, to write the music.

“Even though Michel was 90, he had more energy than any of us,” the editor recalls. “He [Legrand] had a jazz background and we knew Orson wanted to have a jazz-based score.”

Murawski’s job was made marginally easier by the knowledge that Welles wasn’t precious and liked concision. The film’s running time is just over two hours. (Welles once famously said he wouldn’t watch 2001: A Space Odyssey until Kubrick cut it down to two hours.)

Welles shot the movie on every format imaginable – 8mm, 16mm, 35mm, colour, black and white and many different types of film stock, and in several different aspect ratios. Editing on film in the pre-digital era was hugely complex for the director but far easier for Murawski and his team, who were able to cut the material electronically on an AVID.

“Everybody brought so much passion to it, as if taking direction from Orson,” says Rymsza.

There is a sense of Chinese boxes about the project. The Other Side of The Wind has a film within the film – the movie that the fictional Hannaford directs. The attempts to complete the project has also generated two further films, Morgan Neville’s archive-based They’ll Love Me When I’m Gone (also screening in Venice and about its making) and short doc A Final Cut For Orson, about its post-production. Both are also backed by Netflix.

No-go for Cannes

The producers believe the film has a new resonance and topicality in the era of #MeToo and Time’s Up. It is exposing the machismo and sexism of the old Hollywood.

The Other Side Of The Wind was initially supposed to premiere in Cannes.

“Cannes would have been beautiful. Thierry [Fremaux, artistic director] had a beautiful festival planned for us but you move on. It is unfortunate it didn’t work out,” Rymsza says of the dispute between Cannes and Netflix which prevented the film premiering then. He is heartened, though, to have the film in Venice, Telluride, New York and elsewhere before its release on November 2 in theatres and on Netflix.

For Joseph McBride, seeing the film completed is a revelation. After all, he was there on the very first day of production. As a young man, he played the film critic, Charles Pister. “We started filming on August 23, 1970 – so it has been a long time!” the author and historian says. ”I have been involved in this film for most of my life.” He was a producer on the film in the 1990s, trying with Gary Graver to get it finished himself and even securing a deal with Showtime to finance its completion. (This eventually fell through.)

Many were sceptical that The Other Side Of The Wind would ever be finished. There have been suggestions that it was a cursed project and that the material simply wasn’t there.

“I think the film is even better than I expected,” McBride says. “Bob Murawski did a fantastic job of editing the film in the style that Welles would have been very happy with. Welles edited about 40 minutes of the film – the party scenes and the film within a film – and Bob followed that very faithfully. It was a tremendous job technically.”

Now, some are touting The Other Side Of The Wind as an awards contender. If this happens, it would be ironic in the extreme. It seems that Welles, the maverick shunned by Hollywood for so long, is now at last being embraced with open arms.

No comments yet