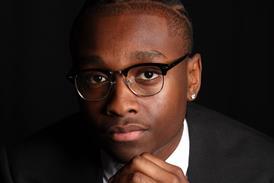

Bikas Ranjan Mishra talks Liz Shackleton through the five-year development and production journey behind his debut feature, Four Colours (Chauranga).

Set in a village in rural India, Bikas Ranjan Mishra’s Four Colours (Chauranga) tells the story of a young boy from the Dalit (untouchable) caste who dreams of going to school and persuades his older brother to write a love letter to a girl from a higher caste. Tannishtha Chatterjee plays the mother of the two boys, a lowly servant who deals with daily harassment and has a clandestine relationship with a local landowner, played by Sanjay Suri.

Produced by Sanjay Suri and Onir’s Anticlock Films, in association with Mohan Mulani’s Surya Ventures and India’s National Film Development Corp (NFDC), the film received its world premiere at this year’s Mumbai Film Festival, where it won the top prize in the India Gold competition. It is screening at Dubai International Film Festival in the Cinema of the World section.

What was the genesis of the project?

The screenplay was prompted by a news headline about a boy who gets killed for writing a love letter. I didn’t want to do a reconstruction of the real incident – I wanted to use the incident as a pretext to examine our society and its contradictions.

I grew up in a village and still have close ties with the place. While writing, I relied a lot on my childhood memory. People whom I knew as a child made their way into the script as characters. I imagined the incident happening in my village. Though something like this never really happened there, the forces that could lead to such a gruesome incident – caste-based discrimination and a huge economic divide – were always present.

How did you develop the script?

The first draft of the script was selected for NFDC Screenwriters’ Lab in 2010, which was held at Locarno. I met my mentor, Marten Rabarts, there, who then headed Binger Filmlab. Marten took a keen interest in my script and spent a lot of time understanding where it was coming from.

What I had submitted for the lab was approximately 60 pages. After the first session of the lab, it became a 120-page draft. The second and final session of the Screenwriters’ Lab happened in Goa and I met Marten again.

What I realised after going through the script with my mentor was that I’d written a bit too much. After the final session of the lab, I was ready to work on the draft further but I wished there was a third session to have a discussion with Marten again.

Around this time I was selected for Berlinale Talents Script Station. I wrote an e-mail to Marten and he was quick to write back and become my mentor for a third time. I spent the four days of Script Station in Berlin giving final touches to the screenplay and going through it with Marten. I kept doing minor improvisations but essentially the draft I achieved in Berlin remained my final draft.

And how did you and the producers approach the financing of the film?

We took the script to Film Bazaar Co-production Market [in 2011] and we received our first cheque [a cash prize for best project in the market].

We also met people from Goteborg International Film Festival at the market, who selected our project for their Script and Project Development Fund. So by the end of 2011, we were sure that we were going to find all the money needed for the film. We planned our shoot for mid-2012.

I spent 2012 finding locations and casting kids for the film. By mid 2013 we were ready with preparations and that’s when Mohan Mulani, our third producer, came on board. NFDC also joined the project as a co-producer. While waiting for funding, we ran a crowdfunding campaign and raised funds to keep the preparations on.

Shooting in Bengal turned out to be much more expensive than we anticipated. The local guild kept surprising us by telling us about new rules. So the production went over budget and we reached out to people all over again for funding. By then we also had some footage from the first schedule to show. This is when Sujoy Ghosh (director of Kahaani), Mind Blowing Films (organiser of Melbourne Indian Film Festival), Raj Suri and others came on board as co-producers.

Onir has worked with Merle Kröger. I had met her during Script Station in Berlin as she was the co-ordinator of the programme. She, along with Philip Scheffner, on behalf of their company, Pong, were one of the first ones to support Chauranga. For us, funding remained an ongoing process. We kept working while money was trickling in. At times, it felt like we had hit a dead end but my producers never gave up. They kept trying and when the traditional means failed they kept trying new things.

Chauranga has in its credit list three producers from two companies, 10 co-producers from six companies and 25 co-owners who contributed during our crowdfunding campaign. Funding is not over yet; we’re now looking for funds to release the film.

What were the major challenges during production and how did you overcome them?

There were challenges of all kinds. First, we were shooting the film in 20 days although it ideally needed a minimum of 45 days. So we were shooting 18-20 hours a day without any breaks to be able to complete the film within budget. Then there were rains, which threw our schedule haywire.

While we had planned to wrap up the shoot in a single schedule of 20 days, persistent rains and a cyclone warning made us pack up on the 13th day. That wasn’t all. We shot the film in Bolpur in West Bengal. The Bengali film industry has these archaic rules imposed by their workers’ guild, which weren’t known to us in advance. They made us hire and pay for local crew members whom we didn¹t require at all. We were forced to hire track and trolley operators despite the fact we were shooting the film handheld. We were made to pay for 20-25 absolutely redundant people every day that burned a hole in the producers’ pockets.

What lessons did you learn from this to pass on to other film-makers?

Though a lot of factors went against us, two things really worked in our favour while making Chauranga. We had a great crew. People who really cared about the film and wanted to make the best film they could make. The crew matters the most. Always find the right people to work with. People who like the project and believe in it. The

‘best’ people in the industry might not always be the right ones to work with. If people really like the project, only then could they go to any length to make it happen. Never rush with the script. A good script needs time. A good script is the one that has all the answers. On the set you will be tempted, at times forced, to improvise, but if you don’t understand the essence of your script you might end up shooting something you never intended to make.

No comments yet