Dir/scr: Antonino D’Ambrosio. US. 2017. 96mins

In 1971, disillusioned New York City cop Frank Serpico took on the systemic corruption he saw in the force and beyond; an action which then saw him labelled as a hero by some, and a traitor by most. With unprecedented access to Serpico, who has lived a largely reclusive life for the past 40-plus years, Antonino D’Ambrosio’s compelling documentary offers an intimate portrait of a man whose personal crusade proved both a calling and a curse.

This is a suitably theatrical precis of a story which has lost none of its impact in the course of time

That Serpico is already globally known, thanks largely to Sidney Lumet’s seminal 1973 feature Serpico (which nabbed Al Pacino his first leading actor Oscar nomination), will ensure there is an eager audience keen to hear the story from the man himself. D’Ambrosio’s filmmaking craft, and the film’s resonant message of injustice and grassroots activism, should also garner plenty of interest following its premiere run at Tribeca.

The film sets out its intensely personal tone from the outset, opening with a brief monologue from the charming Serpico, now in his early 80s. Reflected in a mirror — a nod to the theme of duplicity which is the backbone of his story — he recalls how he used to equate his difficult daily beat as an undercover cop in 1970s New York to the role of an actor. “How well I played those roles, my life depended on it.”

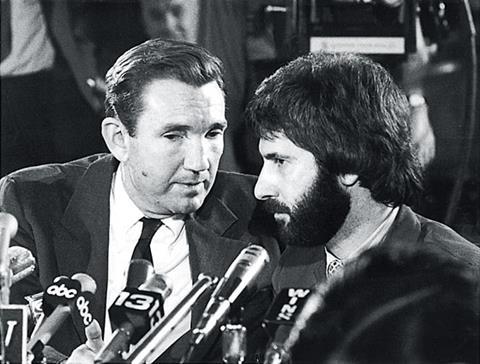

From there, to the strains of Jack White’s frenetic ‘High Ball Stepper’, a fast-paced montage of archive footage recalls how, in the early 1970s, Serpico blew the whistle to the New York Times on the huge number of city cops who were taking substantial bribes from the drug dealers they were supposed to be arresting. Despite hostility, death threats and a near-fatal shooting, Serpico publicly testified against his colleagues at the resulting, and damning, Knapp Commission.

It’s a suitably theatrical precis of a story which has lost none of its impact in the course of time. Indeed, the strength of D’Ambrosio’s approach is not just to reflect on what occurred, but to explore the seismic effect it had on the man at the centre of the maelstrom. Crucial to this is the trust the filmmaker has built with his subject, which goes beyond their shared Italian-American heritage and which enables D’Ambrosio to turn the majority of his film over to Serpico’s own narration.

It’s immediately clear that this is a man driven by the sense of righteousness instilled in him by his immigrant father. “My father said never run when you are right,” Serpico recalls in an emotional walk through the Brooklyn neighbourhood of his childhood which, he also remembers, was overseen by cops who seemed to care little about their community.

Bolstering Serpico’s own reminiscences is the usual array of well-researched archive material and on-camera interviews with those who knew him personally — fellow officers (some sympathetic to his actions, some not) friends, neighbours, literary agents etc — historians and commentators who put his actions into cultural context and those who have been inspired by him, including actor John Turturro and writer Luc Sante.

The real narrative masterstroke, however, is Serpico’s one-man dramatic reconstructions of key events in his life; most notably the early 1971 drugs bust which led to him being shot in the face. Serpico is convinced it was an internal set-up, a theory that seems bolstered by evidence that it was a civilian, rather than either of the two officers he was with that day, who made the emergency call which saved his life. A stilted coffee shop meeting with his former NYPD partner, during which the two share their opposing views of the incident, does nothing to dispel Serpico’s suspicions.

While there’s no avoiding the shadow of Lumet’s Serpico, the film is touched upon relatively briefly. D’Ambrosio effectively layers scenes from the movie over corresponding moments, there’s a short archive interview with producer Dino De Laurentiis and Pacino is heard in a couple of soundbites. What’s more important here is how Serpico himself feels about the work, and there’s fascinating insight into his difficult relationship with the filmmakers and his offense at the dramatic license being taken with his own life. (Yelling ‘cut’ during a particularly disagreeable scene saw him banned from the set.)

Production company: Gigantic Pictures, La Lutta NMC

Iternational sales: Film Sales Company graham.fine@filmsalescorp.com

Producers: Brooke Devine, Brian Devine, Jason Orans, Antonino D’Ambrosio

Executive producers: Brian Devine Sr., Silvija Devine

Cinematography: Karim Lopez

Editor: Karim Lopez

Music: Brendan Canty, Jack White

Features: Frank Serpico, Luc Sante, John Turturro, Janet Panetta, Donna Murch, Stanislao Pugliese

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)