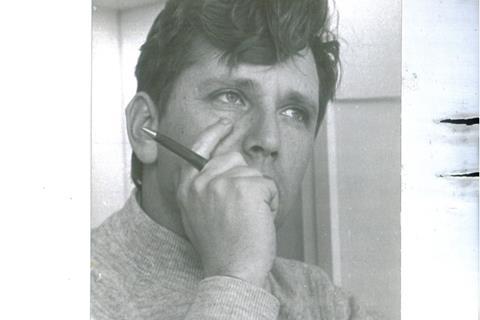

Sober and engaging portrait of seminal Israeli novelist Amos Oz

Dir. Yair Qedar. Israel. 2021. 88mins

It’s easy to feel that everything has been said about the dangers that befall artists who become public property. But there’s a whole new dimension to the pitfalls of fame when an artist comes to be seen as embodying their country; especially when that country is as much conflicted as Israel. That’s the case with novelist Amos Oz (1939-2018), the subject of Yair Qedar’s documentary The Fourth Window. Offering a no-nonsense but comprehensive and involving account of Oz’s life and career, the film uses archive footage, voice-over extracts from Oz’s work, and interviews – including with Natalie Portman and literary heavyweights David Grossman and Etgar Keret– to sketch out its subject’s life and achievement.

A sober, engaging and thorough film that illuminates an unusually fraught life

The film will capture attention, coming soon after the publication of a controversial book by the writer’s daughter Galia Oz that questions his public image; that Qedar eschews the scandalous potential of this topic may lessen its impact. Yet The Fourth Window comes across as an even-handed work that offers significant insight into Oz’s work, character and close proximity to the turmoil of modern Israeli history. Premiering in Thessaloniki before heading to Israel’s Docaviv, the film should have considerable traction in international arts TV and other culturally-focused platforms.

Qedar, whose other literary-themed documentaries include The Awakener and Zelda: A Simple Woman, builds his film around recordings of conversations between Oz and his friend, literary scholar Nurith Gertz, whom, late in life, asked to write a warts-and-all biography of him. The discussions, heard over shots of Israeli city street life from an upstairs window, punctuate an account of a life that, while illustrious, was so tragic that, says Gertz, “the whole story should have been written by Sophocles.”

A determining factor in the life and work of the Jerusalem-born Oz is the fact that his mother killed herself when he was 12. Rebelling against his father, Oz – changing his surname from Klausner – moved to Kibbutz Hulda in central Israel, where he lived and worked for much of his life. When he became successful, he would plough his income from his books into the kibbutz’s finances, but still had to request time off from kibbutz work to write. The film paints a portrait of young Oz as a shy outsider who, although strikingly handsome – so testifies his wife Nili, whom he met when they were in their early teens – didn’t fit into athletic kibbutz culture.

Oz’s key books include memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness – which Portman adapted for the screen in 2015 – and 1968’s My Michael, acclaimed as ‘the Israeli Madame Bovary’ and seen as a breakthrough in its depiction of an Israeli woman whose private life and fantasies subversively flouted Zionist ideals. Oz increasingly become a public figure and a tireless political commentator after the Six-Day War, when his writing against the national mood of euphoria established him as a voice of political conscience. His commitment to a two-state solution to conflict made him a bugbear of Israeli conservatives – although there were contradictions to his position, as he could be seen as an advocate of Zionism while being bitterly opposed to the policies of the Netanyahu regime.

Oz was increasingly criticised, even mocked, as his career went on – Qedar shows an amusing TV sketch about prolific output – with attacks made on what some saw as his excessively refined writing style, and on his 1987 novel Black Book, which proved controversial for putting a North African Jew in centre stage.

While Oz emerges as a charismatic figure, a shadow was cast by his daughter Galia Oz in her recent book Something Disguised as Love, in which she accused him of violence and ‘sadistic abuse’. While other members of the family have contested her account, her father admits that he slapped her and threw coffee at her, and is heard speaking remorsefully of his failed attempts to reconcile with her. Some viewers may feel short-changed that Qedar does not take a more hard-line investigative approach to the accusations, but he pays them due regard while eschewing a tabloid approach that might have made the film more obviously commercial.

Oz is certainly lionised by some of his admirers, including a visibly awe-struck Portman, but Qedar’s interviews offer a range of voices, some dissenting, that all point to his importance both in literature and national politics and culture. (Other interviewees include novelist Nicole Krauss, Israeli eminence A.B. Yehoshua, Guardian journalist Jonathan Freedland — oddly misidentified in a caption as a ‘publicist’ — and historian Simon Schama.) A closing drone shot, taking off from that recurrent street scene into the firmament, brings a faintly kitsch note of overstatement. Otherwise, this is a sober, engaging and thorough film that illuminates an unusually fraught life, and should gain Oz many curious new readers.

Production company: Yair Qedar

International sales: Yair Qedar qedary@gmail.com

Producers: Yair Qedar, Karin Etedgi

Cinematography: Itay Marom, Avner Shachaf, Talia (Tulik) Gal’On, Uriel Sinai, Helge Gerull, Tim Sutton, Nadav Neuhaus, Kesten Migdal

Editor: Nili Feller

Music: Ophir Leibovitch