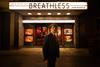

Inspiring primary school principal anchors heartrending documentary set in Northern Ireland

Dirs: Neasa Ni Chianain, Declan McGrath. Ireland, UK, France, Belgium. 2021. 102 mins.

Every schoolboy deserves a Mr. McArevey in their lives. Neasa Ni Chianain and Declan McGrath’s captivating documentary charts the impact of an inspirational school principal and his staff on a generation of boys living in the shadows of Northern Ireland’s long history of sectarian conflict. The bright sparks and troubled souls of the classroom make for lively, sometimes heartrending company in a film that successfully links individual stories to a broader perspective. A Festival journey that began at Doc NYC continues at Dublin and beyond in the run up to a UK and Ireland theatrical release on March 11th.

Observant without feeling exploitative

Young Plato could gain some extra traction from the current success of Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast as it provides a contrasting reflection of life in contemporary Northern Ireland for children around the same age as that film’s scene-stealing Buddy.

The film marks a return to the classroom for Neasa Ni Chianain who co-directed School Life (2016) with David Rane. He now serves as producer of Young Plato. School Life told the story of two teachers at the end of their careers at a rural boarding school. Young Plato is set in an urban working-class community. Holy Cross Boy’s Primary School is situated in Catholic-majority, historically troubled Ardoyne in north Belfast. We know from the opening sequence that school principal Kevin McArevey is a bit of a character. His drive to work is a singalong to Elvis Presley classics as a model of the King shakes and wobbles on its dashboard perch. Presley is a big part of his life as we subsequently learn from an office decorated with Elvis photos and an Elvis clock. You can safely guess the ringtone on his phone.

McArevey is the force behind the welcoming, inclusive ethos of the school. Boys file in hugging and high fiving the principal whilst exchanging good natured banter. McArevey promises the reward of a pound if a boy can beat him in a race. “A pound?, “ says the boy. “I already have a pound!” McArevey is a great believer in philosophy as a means to encourage independent thinking and resolve conflict. We see the youngest boys at their first philosophy session in which they contemplate the question; “Should you ever take your anger out on someone else?” Their answers provide a thoughtful debate and illustrate the way McArevey tries to foster mutual respect between pupils and between staff and pupils. McArevey gives the impression that all problems have solutions, and we see him steer the school through the onset of the pandemic in 2020.

Holy Cross is full of boys facing the same issues as children the world over—bullying, isolation, the pressures from social media, problems at home and lack of self-esteem. The added weight on their young shoulders (no older than 10) comes from a past that never seems to fade. A succession of drone shots float over the streets and homes around the school revealing murals commemorating the IRA or signs declaring: “Loyalist Ardoyne Says No! To Irish Sea Border”.

The directors don’t need to emphasise the influence of The Troubles on successive generations but they gently make you aware that it is a constant factor of life. A local history project brings former pupil Leonard to the school to share what he lived through and to remind the boys that there are still peace walls separating Catholic and Protestant communities. One boy reveals that his grandmother still carries a bullet in her back that has never been removed. The discovery of a device near the school brings home how very real the threat of violence remains. Inevitably, McArevey brings philosophy to bear on the boys’ fears and worries. Aristotle, Socrates or Sartre still have valuable lessons to impart but there is also a good deal of wisdom uttered from the mouths of babes. “We all bleed the same colour, “ says one lad.

Observant without feeling exploitative, the unassuming Young Plato eavesdrops on a number of situations in which individual children are challenged on their behaviour or nurtured in their better instincts. Moments of genuine remorse or growing understanding make for emotional viewing. The positivity of Young Plato is highly engaging, but the directors also ensure we have a sense of what is at stake here. If McArevey and his staff can teach a new generation of boys to think for themselves, question old loyalties and find other ways to manage their anger perhaps they are building the hope for a new Northern Ireland. By the time McArevey drives home from work to the sounds of Presley’s ‘If I Can Dream’ there is unlikely to be a dry eye in the house.

Production companies: Soilsu Films, Aisling Productions, Clin d’oeil Films, Zadig Productions

International rights: Autlook Filmsales, saina@autlookfilms.com

Producer: David Rane

Screenplay: Neasa Ni Chianain, Etienne Essery, Declan McGrath

Cinematography: Neasa Ni Chianain

Editing: Philippe Ravoet

Music: David Poltrock