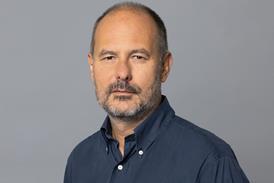

Icelandic director talks to Screen about his latest project The Deep, which receives its world premiere in Toronto.

There’s no chance of Icelandic director Baltasar Kormakur getting bored: yesterday was the last day of principal photography in New Mexico for his new thriller 2 Guns, starring Denzel Washington and Mark Wahlberg and sold by Foresight, and today in Toronto sees the world premiere of his latest passion project, The Deep.

The drama tells the remarkable true story of a man who survived deadly conditions after a shipwreck in Iceland. BAC is handling international sales and WME handles North America.

His future projects include his Viking saga story to shoot in Iceland, as well as Working Title’s Mount Everest project. He is also producing Dagur Kari’s Iceland-set Rocket Man.

Why were you drawn to tell this story?

I’ve known this story since I was about 18. It always stuck with me. In Iceland, we are nation of fisherman, everyone is connected one way or another to an accident at sea. I felt like to tell the story of all of them the best way is to tell a story of one of them who survived. It’s an incredibly difficult and dangerous line of work.

That’s one level, but also what happened in 2008 was everyone in Iceland was talking about stories about the financial collapse. Of course you want to deal with the collapse on some level but I didn’t want to tell the story of a banker or someone who lost a lot of money. I wanted to look at it in a broader perspective, why do people live in a place like this?

There’s volcanic explosions and some places that are almost inhabitable. This was a story that in some way, without giving you an explanation, is a story of endurance and how people from those places can keep on going. Part of this story as well is the 1973 volcanic explosion in the same island and how people kept going. In some ways that’s similar to the collapse. For me it’s kind of a metaphor, it’s a little village as an example for the whole country.

It seems like a film that can be quite specific about Iceland but also quite universal and mythic: one man fighting the elements.

It’s about a man and nature and I think that connects everywhere. It could be people in New Orleans after Katrina.

There is no explanation to it, there’s just an incredible will to survive and keep on going. There were all these tests on him at the time, and no one can come up with an explanation.

At the time the Icelandic media was young and naïve, and they painted him as a mixture of a freak and a national hero.

I tried to tackle all these elements but I’m not handing out any explanations.

What were the physical challenges of shooting at sea?

It’s probably the hardest shoot I’ve ever done. I went to check out all the [studio] tanks, but then I realized that the only way to make this one authentic was to shoot it in the Atlantic Ocean.

It’s a labour of love, I put everything in it. I also wanted badly to understand a little bit what they were going through. When I was in the boat when it went over [shooting the shipwreck], it was probably foolish to do this, looking back now – I was struck by the power of the water when it came in, I also realized how hopeless the situation is for these guys when it happens. The power of nature is way beyond anything you can imagine.

Also beaching to the cliffs, I had to try it myself first to check that it was possible – the waves were really big, you can’t do it on a green screen. You can either do it or not. It’s also a great experience, a great journey.

How did Ólafur Darri Ólafsson embrace the role? Did it take a transformation for him?

In the end he did it all, we had moments of breaking down and almost giving up.

I didn’t want to put him in any situation that he didn’t want to be in, but at the same time I wanted to capture this – the only way to capture this was to go all in.

I haven’t done anything else this physically challenging. We were shooting for weeks with him swimming in the ocean. Every day is different. We just had to deal with it.

I love this kind of stuff, working with the elements. They say Icelandic people are the only ones who would run towards a volcano (laughs).

Your career now includes bigger US films, so why is continuing to make Icelandic films important to you?

I’ve never looked at is as going to Hollywood. I’ve had opportunities to do bigger films that are interesting. Those also help me finance the smaller films.

A lot of the money I’ve gotten from the states is put into this project. This is who I am, this is immensely important to me, this is where I come from, it’s authentic to me and I need to tell those stories.

No comments yet