Dir: Eric Rohmer. France. 2004. 115mins.

Triple Agent is another clever, witty, intelligent morality play by the dean and master of the genre Eric Rohmer, interpreted with his legendary playful earnestness. This is however, by his own admission, the most talkative of his films and as such something of a challenge even for his ardent fans.

Taking place in Paris during the course of 1936-7, it traces through a series of long-winded conversations the tortuous career of a former White Russian general, who fought against the Communist revolutionaries and now holds a key position in the Paris branch of the Russian War Veterans. Mystery hangs over whether he may or may not have served at the same time at least two more masters: the Soviets in Moscow and the Nazis in Berlin.

As such the film is a chamber piece, taking place within meticulously designed if not particularly realistic sets, with bits of newsreels inserted throughout to add authentic flavour. Rohmer's essay on divided allegiances, concealment and deceit, is closer to an enlightening academic lecture than it is to film drama. While it is certain to surface at every festival, it will generate only limited interest on the open market, with better than average chances in Francophone territories.

Rohmer first discovered the details of this still unsolved mystery in an article published by the French periodical Historia several years ago. His script does not pretend to be faithful to the actual events and just like in real life, there is no clear solution provided at the end. Nor is there any clear indication of the actual activities undertaken by Fiodor Voronin (Serge Renko), the main character in the picture.

The story is told through the eyes of his wife, Arsinoe (Katerina Didaskalou), a Greek painter he married during his flight from Russia westwards. All she, and the audience, know about Voronin is restricted to what he tells her, which it soon becomes clear is only an abridged, censored version of the truth that he evades every time she gently tries to pin him down with information that has accidentally come her way.

Is all his extensive travelling through Europe only to serve the Russian War Veterans interests' Is he absent-minded when he omits to tell the whole truth' Is he merely protecting his wife by keeping her in the dark on certain matters' Are his speculations about the policies of Berlin and Moscow based on pure intellectual deductions - or does he know more than he is supposed to'

Voronin tries to justify his actions, to explain his suspicions, to rationalise the political conditions within which he is manoeuvring, and at the same time reveal as little as possible of what he really does. In the end he falls into a trap he has apparently helped set for his superior: but while he escapes the law, his ailing wife is left behind left, found guilty of being an accessory and dies in prison in 1940.

The accompanying newsreel footage used throughout underlines the story's political background which includes not only the situation in France but also across Europe, with ample references to the eruption of the Spanish Civil War. All this is reflected in the Voronin household and its relationship with friends and neighbours.

Trying to make sense of the swift political alterations taking place required a nimble mind and a sharp intellect capable of goals in time for the next twist, something that's not as easy as it might seem. Rohmer's script highlights some of the incongruities typical of that time faced by Voronin. For instance, the French Communists, obedient followers of Soviet instructions, reject the idea of an immediate revolution. Instead they insist that all strikes have to be postponed because social unrest might help the Nazi enemy (they become more confused when Stalin signs a pact with Hitler in 1939).

Beyond the duplicitous morality of nations and ideologies, there is also the moral issue of Voronin's conduct as a person, especially towards his wife, whose doubts and fears, at first hesitant, are confirmed in the last act.

Rohmer's pedantic writing is essential here. Whatever drama there is evolves from the clash between the apparently calm proceedings and courteous dialogue on the one hand; and the dark intrigues of underhand diplomatic espionage on the other.

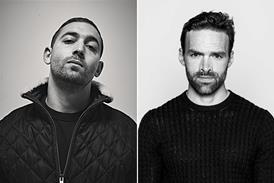

The two leads exude the slightly alien air of foreigners who may speak perfect French (no actor can do less in a Rohmer film) but do not quite blend into the French background. Both Renko, who has appeared in Rohmer films before, and Didaskalou, a Greek actress who has not, evidently relish the urbane, decorous, rounded phrases they have been handed. It is not surprising: in a Rohmer film the dialogue reigns supreme, with no line interrupted before the speaker reaches its end nor interfered with by another character.

If the characters are less affecting than some of Rohmer's earlier heroes (as appear in Ma Nuit Chez Maud, La Marquise d'O, Le Rayon Vert, Les Nuits De La Pleine Lune), then it is not their fault. Rohmer can only have been in his theoretical mode when he wrote and directed this one.

Prod cos: Rezo Productions, Compagnie Eric Rohmer

Int'l sales: Wild Bunch

Fr dist: Rezo Films

Prods: Francois Etchegeray, Jean-Michel Rey, Philippe Liegeois

Scr: Eric Rohmer

Cine: Diane Baratier

Ed: Mary Stephen

Prod des:Antoine Fontaine

Main cast: Serge Renko, Katerina Didaskalou, Cyrielle Clair, Grigori Manoukov, Amanda Langlet, Emmanuel Salinger, Dimitri Rafalsky, Nathalia Krougly

No comments yet