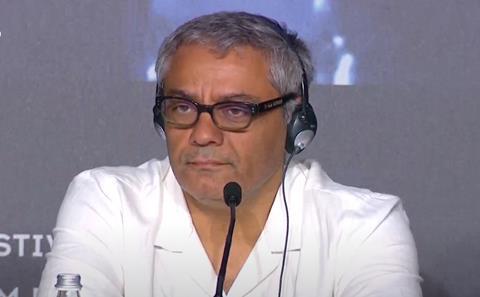

Iranian auteur Mohammad Rasoulof reflected on the secretive methods behind making The Seed Of The Sacred Fig and how he fled his home country while offering a rallying cry to his fellow filmmakers to “not be afraid”.

Speaking at a press conference at Cannes, after receiving a rapturous response at the world premiere of his latest film in Competition at the festival last night, the dissident director also revealed the inspirations behind the feature and how he was hospitalised during the shooting.

“The idea [for the film] springs from years of confrontation with the secret services and censorship in Iran,” said Rasoulof, who has faced suppression in Iran for nearly 20 years and has served prison time for making films that portray life under authoritarian rule.

“All these characters were inspired by real people. All the scenes come from real situations. Even all the people who have known the secret services in Iran will recognise these places. These corridors. The story is very, very close to reality.”

The Seed Of The Sacred Fig centres on an investigating judge in the Revolutionary Court in Tehran, who grapples mistrust and paranoia as nationwide political protests intensify, leading to suspicion of his own family.

Rasoulof revealed how his encounter with an official while serving time in prison inspired the story. “Amongst the prison and legal administration, one gave me a pen as a gift,” he said. “Shortly afterwards he said to me, ‘Everyday when I walk into this prison I look at this door and I wonder when I will hang myself in front of the door… All my children ask me every day, ‘What on earth are you doing? What do you spend all your days doing?’. That was the initial spark which led me to write this story.”

Filmed in secret from late December to March, the filmmaker explained the methods required to avoid detection by the authorities.

“When you have to deal with the secret services, you learn how better to avoid them,” he said. “You understand that they track you using your mobile phone so you learn not to use your mobile phone anymore. Our life is fairly similar to that of gangsters, except we are gangsters of cinema.

“That’s a joke, of course, which we repeated to each other during the filming. We said to each other, ‘If we were to deal in cocaine, it would actually be easier.’”

Hospitalised

Hiding his identity was even required after falling ill with Covid during the shoot. “I caught Covid when we were filming,” he said. “I had a burning fever… and if you go to the hospital, they ask for your ID and they would have known where I was, which would have imperilled the film. In the end, we were able to use the IDs of some village inhabitants and I could be hospitalised.”

Rasoulof also recalled how he was a third of the way through filming when he received news he would be sentenced to eight years in prison and a flogging from Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Court for making public statements, films and documentaries considered “examples of collusion with the intention of committing a crime against the country’s security”.

“At the end of the fourth week of filming, I learned that I was sentenced to several years in prison,” he said. “I wondered whether I could or would be able to continue filming…There was tremendous pressure on my shoulders… [but] I counted on the slow pace of the legal administration to finish shooting the film.”

When the sentence was finally laid down, the filmmaker had just two hours to make the decision on whether to remain and face several years behind bars or leave and “join the culture of Iran that exists beyond its borders”.

“I walked around, I paced around my house, I said goodbye to my plants that I love,” he said, visibly emotional. “It just so happens that the window in my house looks over the mountains and you can also see the walls of the prison. Many of my friends are currently behind those walls. I looked at the mountain, I looked at the wall and I left all my belongings behind me and walked out of the house.”

He explained how contacts he made in prison helped travel to the border before walking a long distance and crossing into a country he did not wish to name. After spending several days in a village, the filmmaker made contact with the European consul, using his time in Germany several years ago to seek asylum.

“Don’t be afraid”

Sending a message to his fellow filmmakers in his home country, Rasoulof said: “My only message to Iranian cinema is don’t be afraid of intimidation and censorship in Iran. They’re afraid. They’re afraid and they want us to feel afraid. They want to discourage us but don’t let yourself be intimidated… They have no other weapon but terror.

“Why are they afraid of the stories we tell in our films,” he added. “They try to repress independent cinema. They are so afraid of arthouse films that they are prepared to prevent the filming of such films. But don’t be impressed by all this propaganda. Don’t be impressed by all these attempts at intimidation by the Iranian government. Remain true to your own beliefs and uphold your freedom of expression to do what you want to do.”

He was joined by cast members Mahsa Rostami and Setareh Maleki, who held up pictures of fellow actors Soheila Golestani and Missagh Zareh, who remain in Iran.

“Choosing this role wasn’t a problem for me at all. It didn’t scare me,” said Maleki. “For months people didn’t tell me who the director was in order to ensure the project would remain safe… but I guessed it was Mohammad Rasoulof. Who else in such a situation could make this kind of a film. Who would have this courage?”

“For me also, it was very difficult to leave the country but I don’t regret it in the least,” she added. “I’m not ashamed either. A lot of people think you shouldn’t say you’ve left the country. I think it’s the Islamic Republic that should feel ashamed, not me.”

The Seed Of The Sacred Fig claimed victory on Screen’s jury grid of films in Competition at this year’s festival, which ends today (May 25) with the awarding of the Palme d’Or.

No comments yet