Dirs: Steven Bognar, Julia Reichert. US. 2019. 115 mins.

Michael Moore’s classic 1989 documentary Roger And Me famously chronicled the shuttering of a historic General Motors auto plant in his hometown of Flint, Michigan, examining the consequences of the closure on the laid-off workers and laying the blame on corporate greed. Now, thirty years later, filmmakers Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert (A Lion in the House) have delivered a similarly vital story in the struggles of labour vs. management in the auto industry, but newly updated and made more relevant for our hyper-capitalist, globalised age.

American or Chinese, they’re all cogs in a system that’s beholden to the bottom line.

In 2014, the Chinese car-glass manufacturing company Fuyao opened a factory in an abandoned GM plant in Dayton, Ohio. For thousands of struggling Ohio workers, this plant meant getting their jobs back after the 2008 recession left many of them unemployed. Both intimate and epic, American Factory offers a remarkably candid, fly-on-the-wall account of what transpired over the following three years between top management and toiling workers, Americans and Chinese, all working together, for better and for worse. It’s a deceptively lighthearted look at one of the most significant cultural and economic conflicts of our times.

Skillfully constructed, American Factory may not have the character-driven allure or celebrity factor of most successful theatrical docs, but it should be widely embraced by film festivals and TV buyers around the world, thanks to its incredible access and topical subject matter.

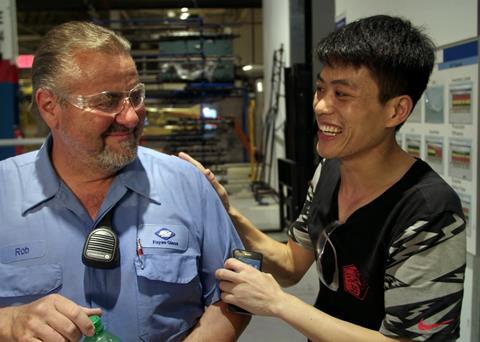

The film’s central culture clash is on display from the start, as Chinese managers try to teach their employees about what it’s going to be like to work with Americans (e.g. “they don’t pay attention to their attire,” “they dislike abstraction”). In private, they are even more candid: while watching the Americans work, they complain to each other, “they’re slow and they have fat fingers.” Despite Fuyao Chairman Cao Dewang’s claim early on that “When in Rome, we do as Romans do,” it doesn’t take long before the Chinese style of doing business bangs up against the ways of the local Ohioans. Before long, pressures mount as the American subsidiary isn’t making its goals and the local workers start to talk about unionising.

American Factory pivots effortlessly between personal stories of the workers, whether a Chinese man whose left his family for two years to help train the Americans or an American worker who saw her wages cut by more than half going from GM to Fuyao, and the larger seemingly unbridgeable gap between the two sides.

In a stark reminder of how far apart the American and Chinese labour styles are, American managers take a trip to China to witness the inner-workings of a Chinese factory, and they are astonished. A spectacularly edited montage reveals that not only does everything run like a well-oiled machine (“Non-stop,” utters one of the Americans in awe), but the workers are completely subservient, counting off like a finely-trained military troop at the start of every shift. They also work 12 hours a day and get 1-2 days off per month. Later, at a special corporate celebration, the Americans are treated to elaborately staged Chinese musical numbers with dancing girls singing about human resources and efficiency.

Back in the US, things are a lot different. (In a funny sequence, an American shift leader tries the Chinese way of lining up his workers, but the results are far from military-like precision.) Meanwhile, the American workers begin complaining about worsening safety conditions, anti-union propaganda, and a lack of respect, while the newly-brought-in Chinese managers are increasingly fed up with what they perceive to be spoiled and over-confident Americans. “We have to train them and teach them, because we are better,” says the new Chinese head of Fuyao America.

Neither side comes across as entirely in the right or entirely innocent. If the Chinese chairman may come across as greedy and callous (“the point of living is to work, don’t you think?” he asks), the Americans seem entitled and oblivious to the harsh realities of the marketplace. But unlike Roger And Me, it’s more complex than us vs. them, corporate vs. worker; rather, they’re all cogs in a system that’s beholden to the bottom line. Towards the end of the film, the chairman is taking a tour through his plant, looking at the newly installed robotic machinery that is allowing for an overall reduction of workers. “Automation. Standardisation,” says one of his staffers. And so it goes.

Production Company: Participant Media

International Sales: Dogwoof

Producers: Steven Bognar, Julia Reichert, Jeff Reichert, Julie Parker Benello

Editor: Lindsay Utz

Cinematography: Steven Bognar, Aubrey Keith, Jeff Reichert, Julia Reichert, Erick Stoll

Music: Chad Cannon

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)