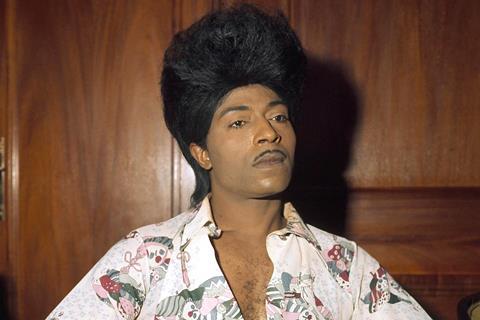

Documentary about the life and legacy of the rock’n’roll icon lacks the dynamism of its transgressive subject

Dir: Lisa Cortes. US. 2023. 98mins

There’s fascination and frustration to be had from this documentary about Little Richard, which is hampered by trying to encompass every single element of the rock’n’roll pioneer’s 87-year life and legacy. Lisa Cortes raises all sorts of interesting ideas – from the singer’s status as a queer artist and influencer to his “born again” reaffirmation of his Christianity later in life – but the film is disappointingly sparing when it comes to performance footage. It also often feels as though topics are being skated over in order to quickly move along to the next one.

Disappointingly sparing when it comes to performance footage

While Cortes – who previously co-directed All In: The Fight For Democracy with Liz Garbus – may not achieve the sparkling showmanship of the man himself, this is nevertheless a crowd-pleaser. The documentary, which has its international premiere at Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival this week before heading to SXSW, was made for CNN Films and HBO Max, which will air the film next month in the US. Magnolia Pictures secured worldwide rights after its premiere at Sundance, and it is due for release in the UK by Dogwoof on April 28.

When Little Richard declares of his influence on rock’n’roll, “I am the emancipator. I am the architect”, there are few who would argue against his huge impact on generations of artists as diverse as The Beatles and Billy Porter. But, despite his individuality and, at least in the early years, unapologetically queer identity, even he was influenced by others. Cortes does an excellent job of evoking his childhood as Richard Wayne Penniman in Georgia, using family photos bolstered by archive stills and footage to stitch his early years as a musician into an engrossing description of America’s so-called ’Chitlin’ Circuit’ of performance venues, which had such an array of black and queer stars it’s ripe for a standalone documentary.

Among those artists who inspired LIttle Richard were the gay and majestically pompadoured Billy Wright and Esquerita – although Cortes’ film continually makes a case for Richard’s uniqueness. One of the devices the director uses to suggest his significant influence is a motif of sparkly CGI dust motes that dance to the music, particularly in sections in which modern artists including Valerie June and John P Kee sing Little Richard cover versions. They look fine but feel basic in comparison to the musician’s flamboyance. Illustrations of the way white musicians like Pat Boone tried to co-opt his music are more enjoyably edited together in ways that emphsise both the sheer cheek of it, and the absurdity.

The film is at its best, however, when we see and hear Little Richard talking or performing hits including ‘Lucille’ and ‘Tutti Frutti’; moments that allow his unpredictable personality to blast out. Yet it often feels as though these performances are being crushed out of the picture, as Cortes cuts back and forth between these onstage moments and her talking head interviewees. People talking direcly to camera is not particualrly cinematic, and it’s a shame Cortes didn’t use more voice-over instead.

Additionally, the documetnary feels over-stuffed in terms of the number of contributors, and the way in which they participate. A scholarly dimension is welcome, but there’s no getting away from the fact that the observations of those who knew Richard personally are the most interesting. Exotic dancer and LGBQT+ activist Sir Lady Java talks briefly about his importance to her self-confidence, but both this and his relationship with the “love of his life” Lee Angel, who also contributed before her death in 2022, lack context. And the fact that Little Richard made no bones about his sexual appetite – “If you knocked on my door and I wanted more - for sure!” – makes it all the more odd that none of his male lovers are interviewed here. (Little Richard himself denounced homosexuality in his later life, after previously speaking openly about his bisexuality.)

Cortes also feels a bit rushed as she tackles Little Richard’s lifelong internal conflict conflict between his gender identity and his religious faith. Although covering the period in which he gave up performance to study theology at Oakwood College in the late 1950s, there’s no mention of the fact that he left after being accused of exposing himself to a male student, or of his arrests for voyeurism.

When the film turns its attention to the lack of accolades Little Richard received until late in life, it comes back to more solid ground. Certainly you’re likely to come away from this documentary with a greater appreciation of the musician’s talent and legacy. But as Little Richard himself once said: “I let it all hang out, every bit.” With Cortes’ film, there’s a sensation that some bits are still being tucked away.

Production companies: Bungalow Media + Entertainment

International sales: Magnolia Pictures mail@magnoliapictures.com

Producers: Robert Friedman, Lisa Cortes, Liz Yale Marsh, Caryn Capotosto

Cinematography: Keith Walker, Graham Willoughby

Editing: Nyneve Minnear, Jake Hostetter

Music: Tamar-kali

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)