Dirs: Nana Ekvtimishvili, Simon Gross. Germany/Georgia/France. 2017. 119 mins.

Directing duo Ekvtimishvili and Gross’s much feted 2013 festival hit In Bloom showed how the lives of two young girls in the former Soviet republic of Georgia were subtly, and not so subtly, constrained by men. Set again in Tbilisi, this follow-up is a small jewel of a film that gives this women-in-a-man’s-world viewpoint a generational shift.

Manana’s steadfast refusal to explain her actions infuriates those around her and intrigues the audience.

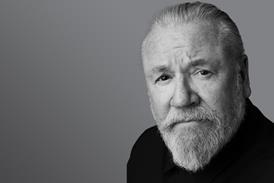

Premiering at Sundance in the World Dramatic competition, My Happy Family tells the story of a middle-aged wife and mother whose decision to leave her family for an apartment of her own becomes, for those around her, an intolerable affront to the natural order of things. Slow-paced but always absorbing, the film features a magnetic central performance by Ia Shugliashvili as one of the strongest, most quietly heroic introverts we’ve seen on screen in a while.

At around the mid point of this two-hour drama, we see Shugliashvili’s 50-something character Manana relaxing in an armchair in the shabby, unfurnished apartment she has rented on her meagre high-school literature teacher salary, facing a French window that opens onto a rusty iron balcony. The leaves of a poplar rustle in the breeze outside; on an occasional table next to Manana is an open book, a slice of cake and a cup of tea; a Mozart concerto is playing on a cheap CD player. It’s Virginia Woolf’s feminist essay A Room of One’s Own distilled into a single, beautiful shot, and like the rest of this film, it’s an image that will resonate with audiences worldwide.

While In Bloom had the bloom of youth as an audience pull factor, this mature follow-up is the more universal film. Though rooted in Georgian culture – especially in the sentimental folk songs that seem obligatory whenever a group of locals get together over a bottle or two – Manana’s story could be set in London, Chicago, Naples or Shanghai. Anywhere, that is, where women are liable to fall into the crack between society’s idea of their happiness, and their real happiness.

What comes before this mid-point moment of calm is the pressure-cooker that has led Manana here. She lives, or lived, in a small downtown Tblisi apartment with husband Soso, a complaining battleaxe of a mother, an elderly father, an unemployed young adult son and daughter, plus the latter’s student husband.

Everyone rubs along more or less between flare-ups, and at first it’s the down-in-the-mouth Manana who seems the sourpuss as she sulks through a birthday party that her apparently affectionate hubby Soso has thrown for her. But she had told him not to invite anyone, and gradually we see how these small but constant erosions of her personal freedom in the name of family ties, good cheer, and social custom have eaten into her soul. Even getting dressed is a challenge: there’s only one wardrobe in the flat, in the bedroom that daughter Nino shares with her husband Vakho.

Working with Romanian DoP Tudor Vladimir Panduru, who shot Cristian Mungiu’s recent Graduation, the directors make the widescreen frame seem a narrow letterbox into which the characters, in continual, restless movement, barely fit. The camera tracks Manana in pretty much every scene, building sympathy but also creating eddies of tension as she moves into and out of spaces of male threat and entrapment. Other women’s stories involving her daughter Nino, an old school friend and a high-school student who is already divorced at the age of 18 impact on the heroine’s own decisions but also paint a picture of a society where the actual kidnapping of a young girl we witnessed in In Bloom, in order to force a marriage, has been replaced by more subtle but no less effective forms of control.

Food, drink and song are three such cultural constraints, and all three are stitched carefully into My Happy Family’s dramatic fabric – for example, in the joyous release we see on Manana’s face when market shopping finally becomes a pleasure, rather than something for her mum to attack her about.

Though warned well in advance, Manana’s family can hardly believe it when she makes good on her promise to move out, especially as (we are told) her husband doesn’t hit her, and is neither a thief nor a drug addict. At this point, a coercive mechanism of little chats and family conferences kicks in, with the aim of persuading her to change her mind: it’s Manana’s borderline abusive brother who comes closest to the real reason for this flurry of concern when he tells her “I don’t want everyone talking about my sister”.

Her steadfast refusal to explain her actions infuriates those around her and intrigues the audience. There’s a never-quite-resolved mystery to this strong but undemonstrative woman that carries us through two hours of slow-build drama - a drama that is given an enjoyable, quasi-comedy twist in the film’s only slightly over-long second half.

Production companies: augenschein Filmproduktion, Polare Film, Arizona Productions,

International sales: Memento Films, sales@memento-films.com

Producers: Jonas Katzenstein, Maximilian Leo, Simon Gross

Screenplay: Nana Ekvtimishvili

Cinematography: Tudor Vladimir Panduru

Editor: Stefan Stabernow

Production designer: Kote Japharidze

Main cast: Ia Shugliashvili, Merab Ninidze, Berta Khapava, Tsisia Qumsishvili, Giorgi Khurtsilava, Giorgi Tabidze, Goven Cheishvili, Dimitri Oragveidze