Dir: Xavier Beauvois. France 2010. 120mins

One-time enfant terrible Xavier Beauvois has long been a respected presence on the French scene, making his name with dramas such as Don’t Forget You’re Going To Die (1995) and the police story Le Petit Lieutenant (2005). With Of Gods and Men, his time for wider recognition has surely come, this thoughtful but urgent piece showing that Beauvois has matured into a masterly director with tight, calm control of his material.

Miles from the edgy, confrontational tenor of Don’t Forget…, Beauvois’s new film muses on the meaning of religious vocation in a violent world, and tackles its difficult subject with authoritative, non-sensationalist forcefulness.

Timely themes - the dialogue between Islam and Christianity, questions of fundamentalist violence – make for a newsworthiness that will boost the film’s visibility in France, where it is released in September.

The religious milieu might seem a drawback for wider sales appeal, but given the surprise niche success of Into Great Silence, the 2005 German documentary about Trappist monks, this accessible and soberly life-affirming film should find solid uptake among buyers of material for discerning art-house audiences. Festivals will pledge their faith big-time.

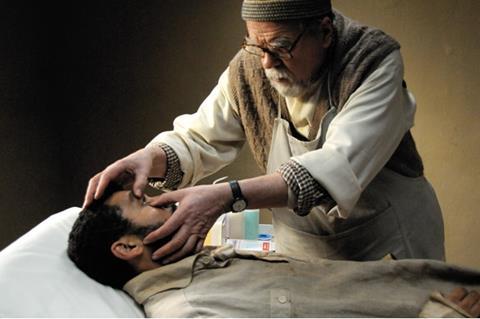

The film is inspired by real events, the still not entirely explained kidnap and murder of seven monks in Algeria in 1996 – but the narrative leads slowly round to the tragedy, which happens only at the very end, and largely off-screen. In a Cistercian monastery in North Africa in the 90s, eight monks live in cordial harmony with the local population. Brother Luc (Lonsdale) is the resident doctor, dispensing tender care and good advice, while the monastery’s head Brother Christian (Wilson) is as much versed in the Koran as in the Bible, giving him a special insight into, and respect for, the Islamic nation he has chosen to work in. But the country is increasingly in the grip of fundamentalist violence: early on, the film’s one piece of explicit brutality, the murder of some Croatian workers, is handled with discreet but arresting effect.

As tension mounts, the brothers must decide whether to stay or leave, Christian coming under pressure from the friendly but increasingly impatient mayor to close the monastery, causing much soul-searching among the brothers, some of them contending with crises of faith. When a fundamentalist militia group turns up at the monastery, Christian trades Koranic quotes with their leader, and a détente is produced – but it clearly can’t last.

Despite the not inconsiderable drama, Beauvois never attempts to make this a thriller à la Costa-Gavras. Rather, he carefully builds up a sense of the coherence and rhythms of the monastic life, interspersing the narrative with scenes showing the monks’ services (the cast contributing some well-tuned Cistercian chanting). Scripted by Etienne Comar with Beauvois, the film is especially compelling in its balancing of theological and political dimensions, showing that its heroes are not living in an ivory tower but are deeply involved in the meaning of their calling in relation to the outside world.

The film is very timely, especially in France, where debate on Islam and the secular domain continues to be a political hot potato. What’s at stake is reconciliation between Islam and Christianity, with both French and Arab characters attacking fundamentalism: the film’s bottom line is that the two religions share a common respect for humanity.

Key moments include a scene in which the monks resist the menacing presence of an army helicopter by effectively chanting it away; and a sort of Last Supper, as the monks enjoy each other’s company to the strains of ‘Swan Lake’. In this scene, cinematographer Caroline Champetier shows a wonderful sensitivity to the actors’ faces, mapping their emotional nuances in intimate close-up.

Visually, the film is in a mode of low-key realism, with imposing but sparely composed landscapes firming up the sense of place. Viewers may detect echoes of Bresson and Pialat, but while Beauvois downplays the flourishes, this shouldn’t blind us to just how much directorial individuality there is here. The ending especially is all the more powerful for being, against expectations, intensely restrained. The ensemble cast downplay superbly, Lonsdale contributing his usual magisterial warmth and Wilson registering intellectual and spiritual conflict with great subtlety. Jacques Herlin also makes a strong impression as the monastery’s wizened but impish doyen.

Production companies: Why Not Productions, Armada Films, France 3 Cinema

French distribution: Mars Distribution

International sales: Wild Bunch, www.wildbunch.biz

Screenplay: Etienne Comar, Xavier Beauvois

Producers: Martine Cassinelli, Frantz Richard

Cinematography: Caroline Champetier

Editor: Marie-Julie Maille

Production designer: Michel Bartélémy

Main cast; Lambert Wilson, Michel Lonsdale, Olivier Rabourdin, Philippe Laudenbach, Jacques Herlin

No comments yet