Dir/scr: Kim Ki-duk. South Korea. 2012. 104mins

Here comes another Kim Ki-duk metaphor, a very Christian one at that, this time about pain - inflicting and bearing it - the corrupting power of money and more than anything the concept of motherhood and misericord in this world. Often weird and freakish, as you would expect a Kim Ki-duk film to be, this gruesome tale about a vile moneylender’s enforcer and a woman who enters his life claiming to be his mother, may well scare off average Western audiences, but festivals and art houses will take it to their heart, just like they did with earlier Kim Ki-duk films in the past.

Starting with a grisly suicide and ending with a burial, this isn’t an easy or pleasant film to watch.

Kang-do (Lee Jung-jin), a grim-faced young brute living in a shantytown that is soon to disappear to make room for yet another cluster of skyscrapers, has lined up for himself a very simple existence. Self-sufficient by definition, he visits one little neighbourhood workshop after another to collect the debts owed to his boss.

If the money is not there, he will brutally beat-up the debtors and then systematically cripple them, breaking their arms, legs, backs or whatever it takes to get the right amount of insurance money needed to cover the sum they have to pay back with the exorbitant interests attached to it. In true Kim Ki-duk fashion, the audience is not spared either the treatment of the victims or Kang-do’s icy, dispassionate, menacing demeanor.

One day a strange woman (Cho Min-soo, whose perfectly made-up face and sad smile seems inspired by the classic Virgin Mary statuettes) starts doggedly following him around begging him to forgive her for abandoning him when he was a baby and accepting every insult, humiliation and injury he can think of to make her disappear from his life. But nothing works.

She moves in with him, cleans up his place and dotes on everything he does, even his most abominable actions, claiming she is responsible for his being like that. It takes a while before she persuades him she has may have indeed given birth to him, at which point, he not only softens and becomes emotionally dependent on her presence, but discovers the meaning and the sense of compassion, of which he was completely oblivious up to that point.

If the transition period looks a bit brusque and obvious, Kim turns the tables on his audience, and in a sardonic twist, hints that things may be just a bit more complicated than one is tempted to conclude after the first part of the film. An ambivalent but quite powerful ending, leaves a bitter aftertaste of inescapable misery and at the same time constitutes a fierce anti-capitalist manifest denouncing money as the ultimate evil perverting us all.

Starting with a grisly suicide and ending with a burial, this isn’t an easy or pleasant film to watch. Meticulously composed frames shot in dark, narrow, spaces which every once in a while open up to wide desolate landscapes that are even less comforting, the camera closing down on the characters in pitiless close-ups, it all serves Kim Ki-duk (who also edited the film) to obsessively forge ahead, revealing with every additional step, yet another ignominious facet of human nature.

Finally, there is the location itself, essential to create the crepuscular world in which all this takes place. The entire film was shot in the heart of Seoul’s once industrial development area, now a disaffected slum, its dingy alleys piled up with garbage and refuse, its buildings dirty, empty and dilapidated, just the kind of place no one would ever want to live in, though there are those who do not have a choice.

Production company: Kim Ki-duk Productions

International Sales: Finecut, www.finecut.co.kr

Producer: Kim Soon-mo

Cinematography: Jo Yeong-jik

Editor: Kim Ki-duk

Production designer: Lee Hyun-joo

Music: Park In-young

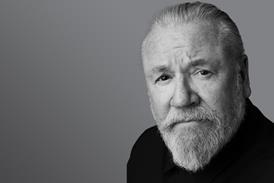

Main cast: Cho Min-soo, Lee Jung-jin