Charlie Brooker and Annabel Jones were unsure about an interactive episode of their anthology series Black Mirror. Then Brooker had an idea, they teamed with producer Russell McLean, and a willingness to evaluate decisions became central to Bandersnatch.

Listening to creator/writer Brooker and producers Jones and McLean discuss the creation of Bandersnatch is rather like watching their pioneering interactive episode of Black Mirror.

Conversation with the trio is peppered with digressions, different voices, pop-culture jokes and cutaways. They discuss Bandersnatch with passion and pride despite the demands of pulling off such an ambitious and innovative project.

It wasn’t always this way. When Netflix first approached Brooker and Jones in early 2017 looking for a show to test interactive technology on their platform, the pair were not keen.

“We said, ‘What a wonderful idea, we’re flattered to be asked.’ And we left the room going, ‘There’s no way we’ll do that,’” says Jones.

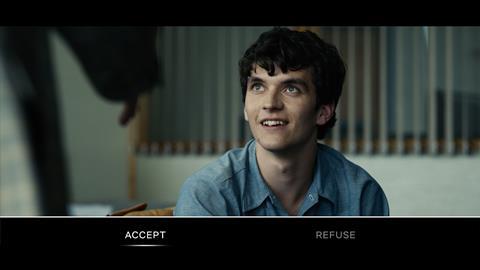

But a few weeks later, Brooker had an idea, and they realised his story — based around his own longtime hobby, vintage computer games — could benefit from being told through an interactive platform. The story centred on Stefan, a young programmer in London in 1984, who is adapting a fantasy choose-your-own-adventure novel into a video game, but it is the viewer who chooses where his story goes.

Once they had pressed play on the project, the potential narratives began to expand far beyond their initial conception. “Somewhat naively I thought, ‘We’ll just do a flowchart and work it out,’” says Brooker. “Then it was like, ‘Hang on, we need a bigger board.’ Then it was, ‘Maybe we need a bit of software for creating a flowchart.’ Then it became apparent that no, that’s not good enough either, what you need is something that can track and remember what’s happened.”

Follow the Twine

That turned out to be Twine, a programming software for interactive fiction. Brooker was again resistant to taking it on himself — “there’s no fucking way I’m going to try and learn that” — but couldn’t avoid his curiosity. “Cut to a couple of weeks later, there I am in my ham-fisted way, trying to work it out. You learn by doing it and it going wrong.”

Even with Brooker’s new skills, he and Jones required a brain familiar with the technical aspects. Enter player three: McLean was brought in as producer in January 2018, having previously worked as a visual-effects producer on 10 Black Mirror episodes dating back to 2013’s The Waldo Moment.

“Russell is so experienced and technically able,” notes Jones. “He was able to get the VFX through, the score, the sound-mixing. All of these things that you take for granted suddenly had to be rethought with new programs. Not many producers could have taken on the enormity of this project.”

David Slade, another Black Mirror alumnus of season four episode Metalhead, joined to direct the story.

It was not just the branching narrative that posed challenges. There were practical questions as well: for instance, how would the choices presented to viewers look on screen?

“We were very keen for it to be elegant and not ugly,” says Brooker. “Originally we thought, ‘Shall we do this in a completely image-based way?’ If you can illustrate the choices without using language, that would make life a lot easier globally.”

They ran tests of short videos illustrating each choice, including one scene in which the viewer must decide if Stefan takes his medication or flushes it down the toilet.

“As soon as we looked at [the shorts], it was apparent it made no sense whatsoever,” Brooker recalls. “The story stopped while these videos were looping around.”

Like much of the project, the solution was meta, cribbed from video games themselves. When moving from one scene to the next, video games have long used a technique that sees the player temporarily lose control of the character, the aspect ratio narrowing as exposition is presented on screen. The ratio returns to normal when the player is given back control. Bandersnatch neatly inverted this, narrowing the aspect ratio for 10 seconds when a decision was required, allowing the viewer to make a choice of two options described in text.

“We made it as simple as possible, almost like subtitles,” says Brooker. “The key was to keep the footage going in the main window, so it doesn’t feel like time has stopped.”

“That just felt the most cinematic thing as well,” adds McLean.

The film — the term the team use to describe it — launched on Netflix on December 28, 2018, and as is the way with much of the streaming giant’s content, the reaction was instantaneous. Fan engagement was widespread, with numerous viewer-created flowcharts popping up online within hours of the show’s release.

“None were as complicated as the actual flowcharts, but I was amazed how accurate they were,” says McLean.

“People got the overall shape of it far quicker than we expected,” adds Brooker. “There’s an Easter egg at the end that we thought somebody might find within a couple of weeks. They found it within five hours of it going online.”

Netflix is notoriously private with its data, and has not given the team viewing figures for Bandersnatch. But the company did offer statistics on how many people picked each option, which gave some interesting — and topical — insights.

One choice, that saw the viewer decide for Stefan to chop up or bury the body of his father, who he has just killed, brought a 52%-48% split, identical to that of the UK’s 2016 referendum on leaving the European Union. “Chop up the body was Remain in that one,” McLean notes.

Multiple choice

Another potential narrative is created with each choice offered, as the vast number of paths leads eventually to one of a supposed 12 different endings — although the creators have not confirmed this, to maintain a sense of mystery around Bandersnatch.

While choose-your-own-narrative media has various precedents, it has never been presented in quite this format nor on this scale.

Jones recognises the novelty brings a new way of experiencing film for the viewer: “One of the funny things, given the theme of the piece, is that we have no control over how people watch it. Ultimately we have to hand it over, and people may make contrary decisions, or they may make decisions that they think we want them to make.”

McLean adds: “We felt we needed to put an exit-to-credits button there [appearing when you reach one of the ‘endings’] — we didn’t want people to feel like they were stuck in an endless loop. You can leave at this point if you want.”

“We were thinking about all the different endings as being one complete Black Mirror series,” says Jones. “All tying into some central conceit — one comedic, one emotional, one horror, one breaking the fourth wall. You have that different flavour, but all through your one central character — the poor sod.”

Has Netflix requested more interactive content after Bandersnatch’s success? “They are open for that conversation, but also recognise that it will work for some things and won’t for others,” says Jones.

Although interactive technology did not feature in the three-episode season five that was released on June 5, Brooker would gladly use it again on Black Mirror: “By the end I was already getting amnesia about how painful it had been at the start. There are definitely ideas swelling around; the key is finding the right story.”

He is even open to the theatrical possibilities. “You could do it in cinemas I guess, and literally have people voting like a democracy. I think you’d get a lot of screaming and yelling.”

As for the creators themselves, which one was their favourite ending? “The one where the producers of the interactive film have a nervous breakdown,” says Jones. “Oh no, maybe that didn’t make it into the edit?”

No comments yet