Screen International corrals well-known faces to share favourite memories from the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) as it celebrates five decades.

People often tell Piers Handling how much they enjoy Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), to the point where the former director and CEO has lost count of the testimonials. But what remains clear, on the eve of the festival’s 50th edition, is a strategy that has endured since the event’s inception in 1976.

“There was a philosophy from the very beginning of Toronto to be non-competitive,” says Handling. “Toronto is now giving more prizes but in those days it was very definitely non-competitive, so the weight of your emphasis changes in terms of the audience you’re trying to reach. Toronto’s focus is on the public. Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Sundance – their focus is on media and the industry.”

Over the years Handling and other passionate programmers applied their knowledge and energy to source the best cinema from around the world for a proud cinephile population. The public-forward approach, in addition to the festival’s location in the heart of an attractive, bustling city in late summer, has proved a potent combination and paved the way for Toronto to become the largest film festival in North America.

Inevitably TIFF – or the Festival of Festivals as it was called until 1994 – has grown to become an essential industry staging post for acquisitions and awards promotion. But as Handling notes: “Despite the fact media and industry started to gravitate to the festival, it was the public that pulled them, and the public is still the most important constituency, in my mind, at TIFF.”

Handling was an army brat born in Calgary who lived in Canada, Pakistan and West Germany as a youngster. He taught film and worked at the Canadian Film Institute in Ottawa from 1971-80, before joining the festival as a programmer in 1982. In those early years, he championed a two-year focus on Canadian cinema, helping to organise a David Cronenberg retrospective in 1983 and the following year serving as programme co-ordinator for the Northern Lights retrospective of Canadian cinema.

Handling was one of a group that launched the Perspectives Canada showcase for national filmmakers that ran from 1984-2001. The programme thrived, bringing Canadian auteurs back into the fold after they had been sidelined during the Canadian tax shelter years of the late 1970s and early ’80s when canny producers turned their attention to commercial cinema.

Toronto caught a wave of emerging national filmmakers. “They were the post-Cronenberg generation,” recalls Handling. “Atom Egoyan, Peter Mettler, Patricia Rozema, Deepa Mehta, Bruce McDonald, Jeremy Podeswa, Guy Maddin.”

When Sandy Wilson’s beloved coming-of-age drama My American Cousin opened Perspectives Canada in 1985, it secured a US and Canadian deal with Spectrafilm and raised awareness of Canadian cinema in North America.

“Patricia [Rozema] went to Cannes Directors’ Fortnight with I’ve Heard The Mermaids Singing in 1987 and then we opened the festival in 1988 with Dead Ringers, which really put David [Cronenberg] on the international map in terms of legitimising him as more than a genre, sci-fi horror director.”

Helga Stephenson had become executive director in 1987 and Handling worked closely alongside her as artistic director. The festival’s budget increased in the late 1980s and a team of ambitious programmers travelled far and wide, expanding the pool of international selections that had been the preserve of fierce rival, Montreal World Film Festival.

Handling spearheaded the launch of the Spotlight programme in 1987 to highlight emerging artists, championing Pedro Almodovar, Krzysztof Kieslowski and Aki and Mika Kaurismaki. The US independent distribution community led by Cinecom and Orion Classics was taking shape by the late 1980s. American buyers began to frequent the festival, and Toronto courted European sales agents that supplied new titles.

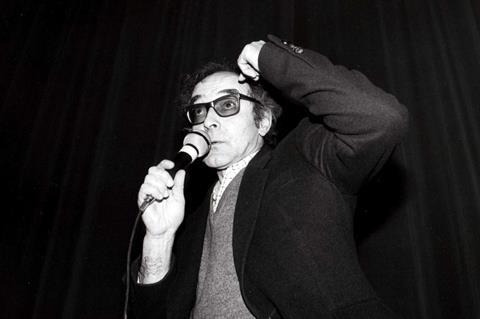

“That was a big deal because the Europeans had always gravitated towards Cannes and Venice,” says Handling. He recalls inviting Jean-Luc Godard to screen For Ever Mozart in 1996.

“Godard had two demands — he wanted us to provide him a tennis pro every day, and he wanted video-editing equipment in his hotel room as he was working on Histoire(s) Du Cinéma. We did both.”

Supply and demand

Alongside the European sales agents, Toronto had also been wooing US independent filmmakers, who saw it as an affordable alternative to costly transatlantic trips to Cannes and Berlin. And where there were talented filmmakers, there were US buyers. An unofficial market had sprung up.

By the early 1990s, the festival bid adieu to its Montreal competitor. “We were an Anglophone festival situated in an Anglophone city, at a point when Quebec was becoming more militant about its [French] language and its politics. Toronto eventually won out.”

By 1994, Handling had assumed the role of director and CEO (until he departed in 2018), the festival’s name had changed to Toronto International Film Festival, and it was finding its feet as a major event on the calendar. “I always felt there was the need for two major festivals in the world — one in Europe and one in North America,” says Handling. “Why not?”

It was a Tuesday at the midpoint of TIFF when the terror attacks unfolded on US soil on September 11, 2001. Handling convened an emergency committee and told a press conference that the day’s festival programming had been cancelled. The decision was taken to resume the following day, albeit in a stripped-down format. Out went the parties, red carpets, trailers and sponsorship logos.

“I’ve never been through a festival that felt like that,” says Handling, “where you were just bringing a filmmaker on stage and showing a film to an audience that was in shock, but also needed to gather as a community. New York is so close to Toronto, and we have many cross-border friendships and connections.”

Handling recalls the pandemonium when planes were ordered to land immediately. Filmmakers and entourages, some of whom could not speak English, were stranded in places like Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Local communities took them in.

Chaos reigned in Toronto, too. “I ran into Glenn Close trying to rent a limo to drive her to New York,” he recalls. “The next night I had dinner with David Lynch and Gene Hackman and they were trying to rent a Greyhound bus and drive across the border.”

Handling believed TIFF had been right to continue. But he wondered if anyone would show up to the 9:30am repeat screening of Mira Nair’s Monsoon Wedding as he walked to the Uptown 1 cinema on September 12, the day after the cancelled premiere.

“It was a big cinema, holding about 950 people. I walked in and the place was packed to the ceiling,” he says. “Then I realised we’d made the right decision and the audience was going to be there for us.”

The public had turned out to support their beloved festival.

No comments yet