Ahead of their Sundance world premiere, the UK director and producer talk about the elusive truth in their film about a Frenchman who impersonated a missing Texas teenager.

The Imposter, premiering in Sundance’s World Cinema Documentary Competition on Jan 23, just may be the best thriller at the festival. The fact that it’s all based on a true story (or, rather, some versions of true stories) makes it all the more incredible.

The film is about how Frederic Bourdin, a then-23-year-old Frenchman, convinced a Texas family that he was their missing 16-year old son. There are even more twists to the story, which stretches from Spain to San Antonio and involves an FBI agent and a resourceful Texas private investigator.

In addition to the revealing interviews, there are some inventive reconstructions and beautiful cinematography to lift The Imposter above straightforward storytelling.

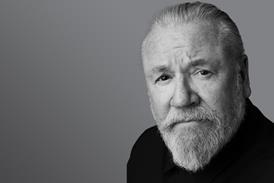

The film is the first theatrical feature made by director Bart Layton [pictured] and producer Dimitri Doganis. Their London-based production company RAW, where Layton is creative director, and Doganis is MD and founder, has previously worked on TV projects including Banged Up Abroad and Gold Rush. Doganis says: “It certainly is a dream come true for us that our first theatrical endeavour takes us to Sundance.”

Oscar winners John Battsek of Passion Pictures (One Day In September) and Simon Chinn of Red Box Films (Man On Wire) executive produce.

The film was backed by A&E Indie Films and the UK’s Channel 4 and Film 4. Protagonist Pictures handles sales.

How did you come across this story?

Bart Layton: I originally found an article about Frederic Bourdin in a Spanish magazine, that was a few years ago [2009]. It was about this guy who was also known as ‘The Chameleon’ who had a series of aliases and had been impersonating damaged children. I thought that was immediately extraordinary.

In looking further we found more articles and more episodes of his life and that seemed like a great starting point for a story about him. The question at that stage was what the story was. We got in touch with him and we met him and it seemed like his story and particularly this episode in which he had impersonated the missing child in Texas [Nicholas Barclay] was a way into a much bigger story which is not just about him as a character, but is about the nature of the lies that we believe and the truths that we create for ourselves.

Dimitri Doganis: We felt like we wanted to have a take on it that was slightly different than anything that had gone before [there was a 2011 French narrative feature about him called The Chameleon]. As Bart says there were themes and ideas that this kind of tragic story gave rise to that hadn’t been fully explored anywhere else before. That was something which was really interesting.

Did you have to earn Bourdin’s trust, or does he still love the media attention?

Layton: He’s quite a suspicious kind of character really. He’s all of the things you see in the film — he is at times incredibly witty and quite charming, and at other times you feel slightly repelled by him. You get all of that, and it was important to reflect that in the film as well.

How did you first approach the family of Nicholas Barclay?

Layton: Poppy Dixon, who is the co-producer on the film, made contact with the family initially. They initially were reluctant to talk about it, but as Dimitri says, there had been a few things published previously and a movie which hadn’t really portrayed them in a terribly favourable light.

Doganis: These other projects hadn’t sought the family’s opinion and I think Poppy spent a lot of time talking about what we wanted to do with the film. Also I went to see them and Bart went to the see them. We impressed on them that we wanted to reflect their experience of these extraordinary events.

Re-enactments can so easily ruin a film. Did you always know you wanted to do re-enactments, and how did you decide to tackle those?

Layton: Re-enactment is a slightly dirty word in TV, let alone in cinema. The thinking there was it would have to be something to reflect these subjective versions of the truth. It’s not trying to convince you that what you are seeing is an accurate depiction. … what we tried to do is to something to encourage the viewer to be aware that this is a subjective version of what happened. That is not what must have happened, this is a visualisation of what someone wants you to believe.

Doganis: I think what Bart and [DoP] Erik Wilson have been able to create is a look where those scenes look like memories rather than reflections of the truth. And I think that’s quite a remarkable achievement. That’s part of why the film feels so distinctive… You’re trying to make a documentary about an elusive truth, and finding a visual medium to represent that.

Layton: Also, instances where the interview and drama overlap in dialogue — the purpose of that is to remind people that this is elements of subjective memory. I wanted to play with all those ideas of memory…When people were describing things that had gone on, it was like they were describing a plot in a movie rather than something that happened in the real world. That also seemed like a good starting point in terms of how you were visualising all of these different versions of what was happening.

One of the most striking things is that as your interviewees are presenting their accounts, there is no indication that time has passed. How did you get them to just talk about those moments as if they weren’t tainted by what’s happened since?

Layton: That’s probably just the nature of doing a long and relatively intimate interview. Part of it is that the interviews aren’t shot with masses of crew and light and sound. We just talked through the stories from start to finish.

The one thing I would also say is that the way it was structured and laid out is that what I wanted to do with the journey that you go on as an audience member is to try and take the audience on a journey that was similar to the one we went on in making the film, when we started, we’d go from one interview convinced of one version of events, and you would come out of another interview completely convinced of the opposite version of events. That was a really strange experience. You felt like you were lurching between different thoughts and conclusions and realities. Rather than setting off on one person’s journey, you were setting off on four or five people’s journeys and as an audience member you are with all of them and you understand the reasons why they want to believe the things they want to believe.

This is the first theatrical film for both of you, does it feel quite different than working for TV?

Layton: you have to think in a completely different way. I remember having conversations which were about how we were going to take what we’d done very successfully as a producing-directing unit for TV and upscale that for cinema. That was one of the most enjoyable challenges I think. We’ve always had ambitions which are bigger than the small screen. We were lucky to work with some totally brilliant people, like DoP Erik Wilson (Tyrannosaur, Submarine) and editor Andrew Hulme (Control), and we had the help and advice of John Battsek and Simon Chinn.

Doganis: Bart’s vision for the film allowed us to bring a huge amount of additional value. What you see on screen is beyond our relatively modest budget. So many brilliant people went over and above what we could pay them for to try and realise that vision.

No comments yet