Adult animation is still regarded with suspicion by mainstream exhibitors and distributors.

Animation is everywhere. Look at the highest grossing films in cinemas worldwide last year: Finding Dory, Zootropolis and The Secret Life Of Pets occupy three of the top five places. Of the others in the top 10, films such as The Jungle Book, Captain America: Civil War, Deadpool, Suicide Squad and Fantastic Beasts And Where To Find Them are full of animated scenes.

At the same time as dominating the global box office, animated films are increasingly prominent at film festivals. It is a decade now since Marjane Satrapi won the Jury Prize in Cannes with her autobiographical animated feature Persepolis, and 16 years since Richard Linklater’s Waking Life opened Sundance. Since then, every self-respecting festival from Berlin to Venice has programmed animated features in official selection — and often in main competition.

In Cannes last month, Tehran Taboo was a talking point of Critics’ Week, a film praised for exposing the underside of contemporary Iranian life (sex, drugs and corruption), even if some critics deemed the treatment of its subject matter to be naïve.

Meanwhile, Chinese filmmaker Liu Jian’s sprawling and violent crime drama Have A Nice Day (in Competition in Berlin, picture below) was likened by several critics to an animated version of a Quentin Tarantino movie.

Annecy International Animated Film Festival this month premieres Loving Vincent, the painted animation biopic of Vincent Van Gogh directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman that has already sold to 100 countries in advance of its release.

And live-action dramas, for example Todd Haynes’ recent Cannes Competition contender Wonderstruck or JA Bayona’s A Monster Calls, are more and more likely to feature animated excerpts.

Nonetheless, a paradox remains. ‘Grown-up’ animation is still regarded with suspicion by mainstream exhibitors and distributors. The old idea that cartoons are for kids has been surprisingly hard to shake off.

The Annecy festival (June 12-17) is hosting a panel discussion entitled ‘What Kind of Economy Exists for “Adult” Animated Features?’. The very fact such an event is being held suggests independent, adult-themed animation remains a tough proposition.

“Still, there is a very big misunderstanding in the audience — and we can’t blame them — that animation cannot be for adults,” suggests one of the panel’s participants, Bruno Felix, co-founder of Submarine, one of the leading production companies in both live-action and animation in the Netherlands.

Numbers for adult-skewed animation certainly are not encouraging. Anomalisa, directed by Charlie Kaufman and Duke Johnson, received rapturous reviews after premiering in Venice in 2015 and went on to earn an Oscar nomination. This was a serious drama about mid-life angst, made on an $8m budget — and it grossed $6.4m worldwide. Films such as Persepolis (with a worldwide gross of $22m) and Waltz With Bashir (which made $11m globally) fared better at the box office. Meanwhile, this is a golden age for Hollywood animation — and one of the defining traits of films, from those in the Pixar canon to The Lego Movie and Despicable Me, is that they appeal both to children and their parents — they manage to be innocent and knowing at the same time.

There is, though, still clear evidence of a two-tier system. Disney’s animated movies go out on thousands of screens in the multiplexes while adult-skewed animation, although now being made in far greater quantities, is kept for the arthouses and given very modest releases.

“Animation [emerging] as a serious dramatic art form is inevitable,” says Tommy Pallotta, producer of Linklater’s rotoscoped animated features Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2006) — and his collaborator on a planned animated feature about St Francis. He predicts that all it will take to change attitudes is “one breakout film that really resonates with audiences”.

So where is that film going to come from? Sony had a notable success last year with its R-rated Sausage Party (below), grossing more than $140m on a film that was made for just under $20m. Its combination of frat-boy humour (male sausages filling female buns) and cheery, supermarket-set slapstick appealed to the same young-male demographic that flocked to Marvel’s Deadpool.

This was far from the first adult-oriented animated feature to achieve commercial success. Ralph Bakshi’s X-rated Fritz The Cat (1972), based on Robert Crumb’s cartoons, is said to have earned $90m at the box office. Both Fritz The Cat and Sausage Party had the feel of novelty items — one-offs. They were not representative of a new trend in adult animation.

Pallotta suggests that what is needed for “grown-up animation” to break through is an equivalent of something like The Blair Witch Project, the low-budget, found-footage horror movie that had a reported budget of $60,000, grossed more than $250m, and spawned hundreds of imitators. A success for an animated film on this scale would change attitudes, and would enable other films to follow in its wake.

At the moment, Pallotta argues, risk-averse distributors and exhibitors are not prepared to commit to the marketing needed to make adult-oriented animated features successful. “It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. There is not an audience for it already that they can quantify,” he says.

If the distributors are not ready to invest in the P&A, cinema-goers will not become aware of the films — and are therefore likely to fail. “I think for the most part audiences are more open-minded than the people who make decisions about what films they will want,” Pallotta adds.

There are obvious hurdles that adult-oriented animated features struggle to overcome. As Belgian 3D specialist nWave’s CEO Ben Stassen points out, “in terms of the business model, animation skewed to older audiences” remains risky. “The ones we’ve seen so far, and there have been some good ones, have been more traditional animation and on the lower-budget side.”

Lower profile

Even when independent, grown-up animation has big-name talent attached, the stars do not sell the movies the same way they would live-action films. A Scanner Darkly featured Keanu Reeves, Robert Downey Jr, Woody Harrelson and Winona Ryder and was based on a Philip K Dick novel, yet Pallotta recalls the marketing spend by distributor Warner Independent remained very modest.

That means the films have a low profile in the market and will not go on to sell well to TV. The prices paid for TV rights to animation, Stassen points out, are far lower than for “regular live-action”.

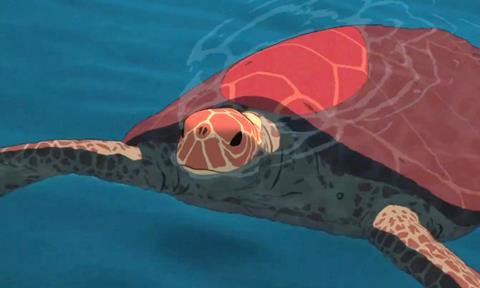

Some recent examples suggest that adult-skewed animation is at last finding an audience. In Benelux, for example, Michael Dudok de Wit’s The Red Turtle (produced by legendary Japanese company Studio Ghibli, pictured above) was a notable success, posting 120,000 admissions for distributor Lumiere.

A poetic and philosophical story about a man stranded on a desert island, the film was very different in tone from the smutty and abrasive Sausage Party — and yet did just as well at the box office in that territory.

“It [The Red Turtle] was an adult movie that you could take your kids to,” Lumiere’s Annemie Degryse says of the film’s success. Its director was Dutch, which boosted local appeal, and Lumiere opened the film shortly after its Cannes 2016 premiere, when the publicity hype surrounding it was at its height.

If The Red Turtle was upscale arthouse fare, one of the most sought-after titles in the Cannes market this year was the quirky, stop-frame animated feature Bubbles, about Michael Jackson and his beloved pet chimp. The film, directed by Taika Waititi and Mark Gustafson, was being pursued by streaming giant Netflix, which was reportedly ready to pay close to $20m for rights.

There is evidence, too, that animated genre titles for grown-ups are also sparking curiosity in the marketplace. In the UK, veteran producer-distributor Joseph D’Morais is working with Wales-based Animortal Studios on feature-length, stop-motion, comedy-horror Chuck Steel: Night Of The Trampires (pictured below), written and directed by Mike Mort and billed as “a lovingly anarchic homage to the rampaging action films of Arnie, Sly and Bruce”.

The film, a spin-off from the short Raging Balls Of Steel Justice that premiered at Frightfest in 2013, has a budget of around $13m (£10m), all raised privately. It is a hefty amount for an independent animated feature. The producers are D’Morais, Mort and Rupert Lywood, with Randhir Singh as executive producer.

“We are doing it the hard way. We are doing 24 frames a second; we’re doing lip-synching — we’re not using stick-on lips,” D’Morais says of Night Of The Trampires, which is expected to be 15-rated in the UK and to have an R certificate in the US. D’Morais points to the way live-action superhero movies such as Deadpool and Logan are successfully targeting an older audience — if they are doing so, he argues there is no reason why animated features cannot follow suit.

“Animation is becoming more of a form not just for children but for documentary, for hybrid films, mixing live-action and animation and for adult animation as well,” argues Femke Wolting, co-founder alongside Bruno Felix of Submarine. The company is currently co-producing animated feature Buñuel In The Labyrinth Of The Turtles, which tells the story of Spanish surrealist Luis Buñuel’s experience making his 1933 classic Land Without Bread (Las Hurdes). Submarineis also using animation in its documentary The Method Bellingcat, about a citizen journalist group famous for its online investigations into everything from drone bombings in Iraq to the use of chemical weapons in Syria.

Drawn from life

There are obvious reasons why documentary makers take the ’toon option: if they are not present at a scene or cannot get hold of archive material, animation can be used as a form of reconstruction. If the film is very harsh in its subject matter, the animation can leaven matters. Submarine’s feature documentary Last Hijack, which screened in the Berlinale, followed a young Somali pirate. Aspects of it were very grim but the animation softened the storytelling and helped the film escape from the straitjacket of cinéma verité.

Those who work in adult-skewed animation are convinced audiences will eventually see its magic. In an era when lines between live-action and animation are becoming increasingly blurred anyway and VR promises to revolutionise storytelling techniques, they argue it is absurdly reductive to confine grown-up ’toons to the arthouses.

For the filmmakers themselves, working on adult-skewed animation offers opportunities and creative freedom. Look, for example, at the legendary former Disney animator Glen Keane, who created Ariel in The Little Mermaid. Keane is giving a masterclass in Annecy and will present his new short Dear Basketball, on which he collaborated with NBA star Kobe Bryant and composer John Williams.

Keane points out that artists in the field do not necessarily set out to target children or adults. “Somebody asked CS Lewis, ‘Why do you write books for children?’ He replied, ‘I don’t write books for children. I write them for myself and children happen to love them.’ I believe that is the same way it has got to be for adults. The stories I have in my mind fit adult themes. One of the reasons I left Disney is that there is a broader perspective that my work wants to connect with — not that it’s in the zone of X-rated in any kind of a sense… but I think of my animation now in terms of a visual poem. I want my animation to connect to people on a deeper, more personal and artistic level.”

“We have to work in getting this weird misunderstanding out of the way,” Felix says of the notion animation is only for the family audience. “Animation is a beautiful way of making a film. It’s not only a way to express deep emotion and to portray very lively and engaging characters. It’s also a way to expand the visual language of cinematic storytelling.”

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

No comments yet