The director of Directors’ Fortnight entry Stones In Exile talks to Wendy Mitchell about working with the band and taking viewers back to the ‘70s

US-based film-maker Stephen Kijak (Cinemania, Scott Walker: 30 Century Man) is in Cannes Directors’ Fortnight with his 61-minute documentary Stones In Exile. The project transports the audience to the world of 1972, in the South of France, where the Rolling Stones were riding high from their number one album Sticky Fingers, but were staying as tax exiles in rented mansion Villa Nellcote. There, they worked on what would become their masterpiece, Exile on Main Street.

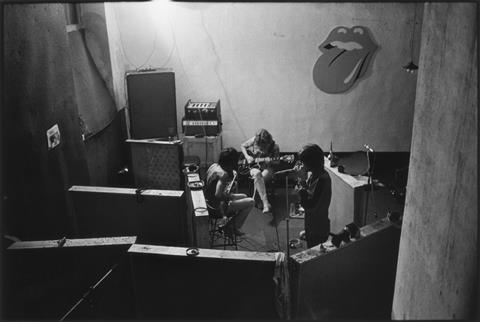

Stones In Exile is comprised of mostly previously unseen archive footage (the bulk of it shot for Robert Frank’s cult classic documentary Cocksucker Blues) with some aesthetically similar new footage that Kijak shot with Grant Gee.

Kijak was recruited out of the blue after Keith and Mick saw his documentary Scott Walker — 30 Century Man. Once he found out what the film would be about, he was 100% on board. “There isn’t a better album in their catalogue, I think, to turn into a film,” the film-maker says. “It’s the richest, deepest, weirdest, most mythological album in the catalogue.”

Stones In Exile came together in just six months, and after its Cannes premiere (May 19, with Mick Jagger attending) it will be released on DVD in June. BBC Worldwide handles sales, and Universal Music Group is releasing the album this week with 10 never-released tracks.

Was this project something the band had been wanting to do for a while?

Mick had mentioned it was always something he had in the back of his mind, there should always be a film about Exile. It does tie into the fact that they are re-releasing the album. It’s a good moment to re-examine the record and that period of time.

How much new footage was shot?

It’s mostly archival, and that was great way to work. There’s not a talking head in the whole thing, except a few very brief interviews with fans of the album. We wanted to dip people right into this time-travel trip, you are really in the ‘70s. I conducted a new string of interviews with everybody, back at the studios, and Grant Gee and I ran around filming stuff, Robert Frank style. We really to make a homage to the prime source material, which was Robert Frank’s Cocksucker Blues. We wanted to orbit that aesthetic. We filled in things here and there. But it’s mostly archive.

Everything we shot was on 16mm, on the old Canon just like Robert Frank used. We wanted it really to all feel the same. There’s a hint of the contemporary Stones in there but it’s more of a nostalgic sort of vibe.

How exciting was it to get your hands on that archive material?

In their mysterious film vault outside of London in an unnamed location, they had all the outtakes from Cocksucker Blues. I had access to about 20 or 30 reels. It was so much cool stuff to look at, and we used a lot of it.

Frank had filmed enough around the concert, backstage, on the road, homes, houses, he really created a rounded world, he filled in all the blanks. We just used it and found ways to repurpose it and use it to tell our story, in cooperation with Dominique Tarle, the photographer who was down in the Villa with them that whole summer. He was another big collaborator, his photos really tell the story of that summer in that house. That was a huge visual resource at our disposal.

How collaborative was the filmmaking with the band?

They were really involved. Mick would pop into the edit. They were very involved, and Keith would have to sign off on stuff. For all that, for all the control they might have of their careers, we got away with it. We made a really weird, unconventional film that flickers and shakes and is all made of old film. It’s a really cool, grungy aesthetic. It was a risk and they backed it 100%, and that is extraordinary.

Was there a lot of debate?

That’s the process, there is always a back and forth about this shot, that shot, why she’s in it, why she’s not, nothing out of the ordinary. This is how you make a film, there’s a lot of cooks in the kitchen, but I think with a great producer and rational people involved we got the film we wanted to make. I know I got the film I wanted to make. Granted, I wish it could have been about two and half hours long because there were so many goodies I wanted to keep on the screen. But it’s an hour, we had to make some painful editorial decisions like you always do.

Was it strange being more of a director for hire after a labour of love like Scott Walker?

Are you kidding? It was awesome. “Hi, we’re the Rolling Stones and we’d like you to make a film for us.” My god, yes. It’s a dream come true. You get into this deep well of musical history of images and sounds and stories, it was really the perfect next thing for me to do after my five-year-long labour of love. This was the perfect antidote to that, we did it in about six months. It was: Here’s the budget, here’s the producer, go.

But you can make it personal. For me it’s about process, I’m very interested in process. I love how musicians create stuff. It’s an album but it’s also this incredibly legacy … it just goes beyond the music on the record. It’s the whole myth of it, that’s just great to work with.

Will non-Stones fans appreciate this film?

What we tried to do it take it back to that place. It’s really about them in that time, in that period, being the coolest people on the earth, looking gorgeous, living in the south of France. Before the stadium tours and all that stuff, there was a real edge there, they were the rebels yet they were also the biggest band in the world. You don’t get rock stars like that anymore, sadly, I don’t know if there ever can be.

No comments yet