After decades of slow but steady development, Indigenous filmmaking – in North America as well as Australia/New Zealand and northern Europe – has recently been gaining momentum and visibility. And genre films have been an important part of the sector’s growth.

In Canada in particular, films like Jeff Barnaby’s Blood Quantum and Danis Goulet’s Night Raiders, which won its writer-director the Emerging Talent award at last year’s Toronto film festival, have broadened the audience for Indigenous film and helped a new generation of on- and off-screen Indigenous talent gain invaluable experience.

The significance of genre films comes under a contemporary spotlight at this year’s TIFF Perspectives conference session on narrative sovereignty in Indigenous filmmaking. But it’s a significance that in part stems from the recent and deep history of Indigenous peoples.

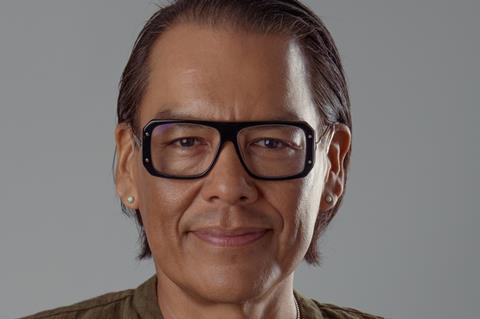

With elements like supernatural beings and alien invasion, genre films can sometimes reflect Indigenous people’s ancestral stories and experience with colonisation. They can also provide a framework for Indigenous stories that is familiar to wider audiences, suggests Bird Runningwater, the Cheyenne and Mescalero Apache producer who is moderating the TIFF conference session.

Native Americans “have been erased from American popular culture up until the last couple of years,” says Runningwater, who recently ended his long run as director of the Sundance Institute’s Indigenous programme. Filmmakers, he suggests, “can fill the genre form with Native characters and a Native story to allow an audience to digest the notion of modern Indigenous people more easily.”

Over his two decades at Sundance Runningwater often saw filmmakers challenged “to dive deeper into their own Indigenous culture to see what more they could infuse their films with.”

As the Indigenous film community evolves, filmmakers “continue to reach back into their personal histories and their own cultural connections,” says Runningwater, now producing under a first-look film and TV deal with Amazon Studios.

Among the current generation of Indigenous filmmakers taking part in the TIFF conference are Darlene Naponse, the Anishinaabe director of romantic drama Stellar (screening at Toronto in the Contemporary World Cinema section), and Nyla Innuksuk, Inuit director of Slash/Back, a sci-fi adventure about a group of teenage girls battling an alien presence in their tiny Arctic hamlet.

Innuksuk says she has always been drawn to genre films, especially horror and adventure fantasies. But growing up, she recalls, “when people were talking about Indigenous cinema they weren’t talking about genre, they were talking about documentaries or heavy dramas.” And for her, “exploring stories that are different from the ones we’ve normally seen told about us is something that’s really exciting.”

Still, Innuksuk acknowledges that in genre projects Indigenous filmmakers are “able to tell stories that can touch on issues that are really hard for us to talk about within our own community, or that we feel other people wouldn’t want to see a movie about.”

She adds, though, that making Slash/Back (which premiered at SXSW and recently secured a US deal with RLJE Films and streamer Shudder) involved finding the right balance of the lighter elements with an alien invasion theme that might evoke a darker response from Indigenous audiences.”

“What I really wanted was to make a fun movie that kids could watch,” Innuksuk says. “I knew people would lay this narrative of colonisation on top of that. That I didn’t have to do anything [to make the comparison] and that if I were to do anything it might feel heavy handed.”

The commercial potential of Indigenous-themed genre films was illustrated by the recent debut of Prey, a fifth installment in the Predator action sci-fi franchise, on Disney-owned streaming platform Hulu. Set among a band of Comanche Nation people 300 years ago and pitting the franchise’s familiar alien predator against a fierce young female Comanche warrior, Prey delivered the biggest premiere of any film or TV show on Hulu to date.

Though director Dan Trachtenberg and writer Patrick Aison are not Indigenous, Prey had an Indigenous producer in Jhane Myers, a Comanche and Blackfeet artist and filmmaker who worked alongside franchise producer John Davis and Marty P Ewing.

“As a creative producer I was able to touch every part of the film,” says Myers, “all the way to the music and the end credits animation.”

Trachtenberg and Aison “were really open to what I had to say and what I had to offer,” reports Myers, who brought cultural nuances to the project and helped create a full Comanche-language version of the film that’s available alongside the English-language version on Hulu and Disney+ (see sidebar).

Myers also worked on an internship programme that brought around 75 Indigenous crew members to the project, which was shot on Stoney Nakoda First Nation territory in Canada. “This film breaks so many barriers and shifts paradigms for native people and native language in film,” she enthuses.

Bird Runningwater suggests that a project like Prey could open new ground for Indigenousfilmmakers – and not just those working in the genre space.

“A lot of contemporary Indigenous filmmakers really despise the period piece because that’s where we’ve always existed in the canon of American cinema,” he points out. “We’ve always been the subject of it, without any agency or our own participation.”

But when he saw the first rough cut of Prey, Runningwater says, “I recognised a really radical shift of the lens on the period piece. It was deeply and thoughtfully and aesthetically Comanche, in a tribal, cultural sense.”

Now Runningwater is hoping that the performance of Prey will “influence other Indigenous-led projects – not just period, but genre and all other forms – to be supported by the industry and by streamers.”

Television projects, both genre and non-genre, should also help drive the Indigenous sector’s growth.

Acclaimed FX comedy series Reservation Dogs, created by Native American Sterlin Harjo and Maori New Zealander Taika Waititi, has already provided a platform for Indigenous writers and directors including Blackhorse Lowe, Danis Goulet, Sydney Freeland and Erica Tremblay. And it has made leads Devery Jacobs and D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai part of a pool of Indigenous on-screen talents – now also including Prey star Amber Midthunder – with marquee value to film and TV backers.

Next year, Marvel series Echo, featuring a deaf Native American superhero played by Native American actress Alaqua Cox, is likely to boost the Indigenous sector’s profile still further.

The success of Prey, Reservation Dogs, Slash/Back and other projects has already caused what Nyla Innuksuk sees as a shift in the attitude of the wider film and TV industry.

Indigenous filmmakers, says Innuksuk, “have been talking about things like authentic representation for a long time. And it’s been really nice to see this shift where, when we’re talking about the importance of Indigenous people telling our own stories, we’re being heard and people are respecting that.”

How Prey secured a Comanche-language dub

When it was launched as a streaming premiere on Hulu and Disney+ in early August, Prey became the first ever feature made available in an entirely Comanche-language version, according to producer Jhane Myers, and the first made available on its initial release in any Native American language (the first Star Wars film got a Navajo-language version, but only decades after its initial release).

Though originally conceived with all-Comanche dialogue, the adventure drama had been shot with characters speaking the Native American language only at the start of some scenes before switching to English. But when the filmmakers began reviewing footage, “the scenes that really popped were the ones that had Comanche in them,” reports Myers. “That’s when we got the greenlight to do a Comanche dub.”

Myers – a Comanche and Blackfeet American Indian whose resume includes dialogue coach credits on such projects as 2017’s The Magnificent Seven and Western TV series 1883 – first translated the script with language advisors Kathryn Pewenofkit Briner and Guy Narcomey. Then a member of the film’s mostly Indigenous cast rerecorded their parts in Comanche, sometimes learning the lines with the help of guide tracks.

Working with Pixelogic, the Los Angeles-based entertainment industry localisation and distribution services company, Myers says her team even went as far as tailoring the translated dialogue to better match the actors’ lip movements as they were delivering the dialogue in English on screen.

The availability of the Comanche-language version is “one of the beauties of being able to stream a film,” says Myers, and “only adds to the authenticity. For my tribe, we’ve never had a whole film done in our language. Just for Native tribes in general, we’ve never had a brand new film that has come out with an option to watch it in its true language.”

No comments yet