Isabel Heguera’s enchanting animation springs off a 1905 Muslim feminist text

Dir: Isabel Herguera. Spain/Germany. 2023. 86 mins

Sultana’s Dream has ‘labour of love’ written all over it. Developed out of the 1905 feminist parable by Bengali writer Begum Rokeya, or Rokeya Sahkawat Hossain, this visually resplendent if dramatically unfocussed feature animation debut by Isabel Herguera about a young Spanish woman´s globe-spanning journey to intellectual and spiritual awakening feels like immersion in a new and unusual world, with all the challenges and rewards that brings. Ultimately there are more of the latter in this impeccably well-intentioned piece, though what really stands out is not the story but the involving, enchanting manner of its telling. This alone should guarantee that Sultana’s Dream wakes up at further festivals, following its debut in competition at San Sebastian.

Magnificent and highly stylised visuals

Apart from delving into Hossain’s work and life, this is also a personal piece from Herguera. The opening scene shows graphic artist Ines (voiced by Miren Arrieta) reflecting on her fears of being looked at by men as a young girl: her journey will in part be towards freedom from such concernss, towards the ability, as she says, to dream her own dreams. Following a failed relationship, Ines heads to India to visit Amar (Manu Khurana), a freedom-loving urban type with whom she has an non-committed relationship

In a bookshop, Ines comes across a copy of ‘Sultana’s Dream’ by the writer and educationalist Hossain. It’s a surreal and utterly remarkable feminist parable about an alternative world called ‘Ladyland’, run by women, where the men are considered dangerous and have therefore been locked up. Amongst Ladyland’s many plus points are that people work only two hours a day and that the women have invented a machine that instantly - and without violence - puts an end to war.

Back in Spain (and specifically in San Sebastian), Ines visits a conference with the real-life philosopher and gender theorist Paul B. Preciado. Paul and the other characters, including Ines´s wheelchair-bound, oceanographer mother (Mireia Gabilondo) and Bollywood director father, tend to talk a little too much in soundbites: “If people spoke less, they’d be happier”, for example, or: “Facing reality is noble”. An animated version of the high-profile British academic Mary Beard pops up, discussing the first time in the history of literature that a man tells a woman to shut up (Telemachus to Penelope in ’The Odyssey’). Although the marketing of Sultana’s Dream stresses Beard’s involvement a bit too heavily, it is evidence of the film’s seriousness: it could serve to youngsters everywhere as an introduction to the theoretical underpinnings of feminism.

Having travelled to Rome to watch her father make a film (his attitude to feminism is that “it sells”), Ines then heads off to Kolkata. Here she finds a soulmate in teacher Sudhanya, and will learn a lot more about Hossain and her world – a world, if one wonderful scene in particular is to be believed, whose values remain largely unchanged more than 100 years later.

A lot is going on under the deceptively simple, 2D animated surface of Sultana’s Dream. Questions are raised about gender dynamics and the suppression of women’s voices, about whether Western feminism can be imposed upon non-Western cultures, and the male gaze: starting with the blind taxi driver who accidentally kills someone at the start of the film, eyes are one of the film’s many symbolic motifs.

Herguera is probably taking on too much and there’s the sense of much being left unexplored as Ines advances towards self-knowledge. A couple of the scenes and characters feel surplus to requirements – those featuring Preciado and Beard, for example – as though they’ve made their way into the film at the request of the director rather than answering to the requirements of the film itself.

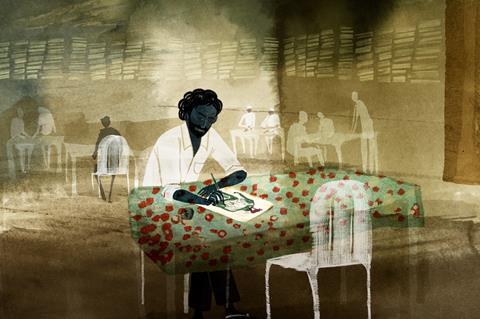

But these and other imperfections – the sometimes awkward and clumsy delivery and pacing of dialogue, for example – are largely forgiven when we turn to the magnificent and highly stylised visuals, conceived by Herguera as a way of not ‘westernising’ the story too much. This is not a film for those seeking accurate representations of real life, while the decision to use three animation techniques depending on the subject matter at the time is high risk and might threaten to break up the visual flow - but it succeeds, and there is a joy in simply watching such high-level craftsmanship unfold.

Ines’ journey itself is represented using digital figures against a hand-painted warercolour backgrounds, with delicious attention to detail: every word on a Wikipedia page is legible, and there’s something compelling about an animation of a phone screen being scrolled. The imaginative marvels of Ladyland are brought faithfully to life using an animated version of the Mehndi style of temporary tattoos, while traditional cut-out animation is used for Dream’s standout sequence, a standalone summary in song of the life of Hossain herself. Herguera’s imagination, like Ines’s, thus finds its truest expression across a range of environments from the city to the jungle, from chaos to peace, and, most importantly, from dream to reality.

Production companies: El Gatoverde, Goya Sultana, Abano, Uniko, Fabian&Fred

International sales: Square Eyes (wouter@squareeyesfilm.com)

Producers: Diego Herguera, Mariano Baratech, Chelo Loureiro, Ivan Minambres, Fabian Driehorst

Screenplay: Isabel Herguera, Gianmarco Serra

Cinematography: Eduardo Elosegi

Editing: Gianmarco Serra

Music: Moushumi Bhowmick , Tajdar Junaid

Main voice cast: Miren Arrieta, Mireia Gabilondo, Paul Preciado, Manu Khurana, Mary Beard