A snapshot of the life of French writer Annie Ernaux, as told through lively home video footage

Dir: David Ernaux-Briot, Annie Ernaux. France. 2022. 61mins

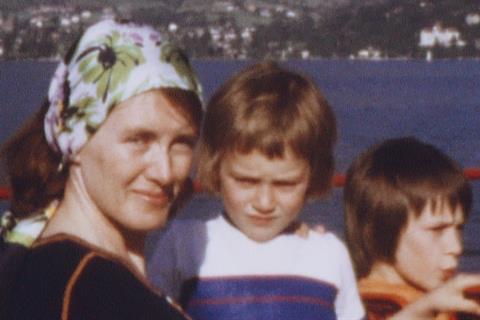

Today, at age 81, author Annie Ernaux is an uncontested major figure in French letters, known as a chronicler of women’s lives – especially her own. (She has just published a novella-length book about her three-year affair in the 1990s with a man 30 years her junior.) But in 1972, when her husband Philippe Ernaux bought a Super-8 camera to film family life with their two young sons, she was a schoolteacher and he was an administrator at the city hall of Annecy. This short, sharp personal documentary is a chronological assemblage by one of those sons, David Ernaux-Briot, of silent home movies shot over a period of eight years, overlaid with informative non-stop narration written and spoken by Annie herself.

Annie Ernaux’s commentary is a time capsule of her life half a century ago but also, by extension, of fascinating changes afoot in France itself

This bittersweet look at the passage of time, delivered with a compelling blend of personal intimacy and broader societal upheaval, is likely to grace many a festival after its premiere in the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes. In the past year or so, Annie Ernaux’s output has provided rich source material for three films, not counting this one: Audrey Diwan’s Venice prize-winner Happening, based on Annie’s search for a clandestine abortion in the early 1960s; Danielle Arbid’s Simple Passion, about a woman completely subjugated by her sexual desire for an unsuitable man; and as a resident of the built-from-scratch Paris suburb of Cergy-Pontoise in the doc I Have Loved Living There by Regis Sauder. Eric Rohmer immortalized the ‘burb by shooting L’Ami de mon amie”/My Girlfriend’s Boyfriend there in 1987. It is also where writer-director Celine Sciamma grew up.

In The Super 8 Years Annie’s voiceover narration tells us that Philippe Ernaux — she never refers to him as “my husband” or simply “Philippe” but always “Philippe Ernaux” — was the family cameraman more or less by default. And he was a good one. The shots are steady and well-composed, the zooms judicious, everything in focus. And one could get the idea that the sky was always blue in France between 1972 and 1981.

In his found-footage assemblage, Flickering Ghosts of Loves Gone By, which premiered unnoticed in Cannes Classics last July but was released in France to justified acclaim on April 20th, Andre Bonzel posits that home movies are so touching because they almost always depict happy times — holidays, birthday parties, Christmas around the tree, etc. So it is for many years with the Ernauxs. David’s birthday is December 25th and so there’s annual footage of the tree and gifts and candles on cakes. Annie’s widowed mother lives with them at first. They visit her in-laws, who have more social status than Annie’s working-class family.

They have footage of a trip to Chile — where President Salvador Allende welcomed their tour group for an hour and they saw the first woman in space, a Russian cosmonaut, hand out school uniforms — of mid-1970s Moscow and, of all places, Albania (a harrowingly sad totalitarian place that was the only holiday destination available at the last minute). There is footage of the beginning of time share units in the French Alps when ski vacations caught on with the middle class. Trips to Spain and Portugal, and to London where she had been miserable as an au pair for 6 months in 1960 and where the family stays in Soho, are the object of very lively vintage images.

Assuming the viewer knows who she is and how far she has come in life, it’s almost an afterthought that she is writing books in secret. She sends the first completed manuscript on spec at the age of 33 and it is accepted by arguably the nation’s top publishing house, Gallimard. “A book doesn’t change your life the way you hope or expect,” she tells us in retrospect.

As the boys grow up and the marriage grows more contentious, Annie goes on writing and publishing but she tells us she’s mostly wondering how she ended up in the role of nurturing mother and spouse when she was raised to believe that women and men are equal. As signposts in the passage of time, she cites politicians and scandals that will be second nature to French viewers and likely more obscure for most others.

When the mariage comes to an end, Philippe takes the camera but leaves the projector and the filmed evidence of a former life with Annie, along with custody of David and Eric. David decided to revisit the reels when his own children expressed curiosity about their grandparents. And so the analog treasure trove was dug up and watched with fresh eyes. And, as a born writer, Annie’s commentary is a time capsule of her life half a century ago but also, by extension, of fascinating changes afoot in France itself.

Production Company: Les Films Pelleas

International Sales: Totem Films, hello@totem-films.com

Producers: David Thion, Philippe Martin

Screenplay, narration: Annie Ernaux

Cinematography: Philippe Ernaux

Editing: Clément Pinteaux

Music: Florencia Di Concilio

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)