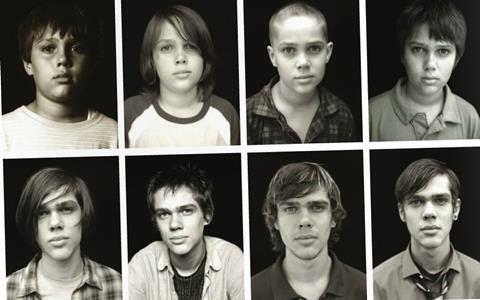

The team behind Richard Linklater’s Boyhood talks to Jeremy Kay about the challenges and rewards of bringing to life this extraordinary 12-year project

It was September 2001 in Venice, and Richard Linklater was enjoying the post-premiere buzz on Waking Life. He was happy but restless. A new idea tugged at his thoughts and he needed to share it.

“It was in my mind for a few years to make a feature about growing up and boyhood,” says the Austin-based film-maker. “Once I struck on this idea I jumped into motion.”

It turns out Linklater could not have been in better company, as he outlined his vision for a 12-year chronicle of youth to two friends who were prominent film executives. The involvement of both would be critical, although they were initially flummoxed.

“I thought it was inspired, slightly crazy but brilliant, and that it was going to be very hard to finance,” says John Sloss, the New York-based industry veteran who had packaged Waking Life and would serve as a producer on Boyhood.

“As a lawyer I thought it was fraught with challenges, the nature of bonding people for 12 years, especially children… it creates all sorts of danger signs. But it happened better than any of us imagined.”

Sloss and Linklater took the idea to Jonathan Sehring, whose IFC Films had invested in Waking Life and, like Sloss, had collaborated with Linklater on the 2001 Ethan Hawke drama Tape.

“Nobody had ever done something about growing up in the way he wanted to do it,” says Sehring. “He said he wanted to shoot the family from first grade to 12th grade. My eldest was in high school and our two youngest were in kindergarten and first grade, so I got it.

“The only thing I could draw as a parallel was 7 Up, but Rick said this would be a fiction film, a little autobiographical. He wanted to draw on his experiences. It was like, ‘OK, we’re in.’”

“I got lucky,” says Linklater, who had already enlisted the support of Hawke and Patricia Arquette as the on-screen parents. “IFC thinks long-term. There’s a big corporation with a big library and they have to have a long-term plan.”

Everybody moved fast to execute the idea that over the next 12 years, would ebb and flow throughout their creative lives.

“I talked to the people I worked for,” says Sehring. “My boss, Josh Sapan [of Rainbow Media, IFC’s owner before AMC Networks], didn’t have a moment’s hesitation. He said we should do it.”

An unusual finance plan

While Linklater assembled his cast and crew, Sloss and Sehring began to thrash out the deal points on what would become a $4m-plus production.

“We structured it in a way that took a little pressure off [Sehring],” says Sloss. “He committed to finance the first year and could stop at any time, but if he did we could bring in someone else in a more favourable position.

“It took pressure off him and still created enough for us to be able to go out and find other financiers if IFC changed their business agenda. Jonathan stuck with it. Rick and the cast stuck with it. About 400 crew people worked on it throughout.”

“It’s almost like financing a short film every year,” adds Sehring. “We did it on an annual basis. We were committed for 12 years and a big part of the production process.

“In terms of finance, Rick would come to us every year and we’d talk about the project and we would give him roughly $200,000, give or take 10%. That was our commitment, and it doesn’t include post and music, etc.”

The role of a lifetime

Pitching a short film every quarter of every year for 12 years made for some tricky meetings with Sehring’s corporate paymasters but the executive’s powers of persuasion, and his production and acquisition track record at IFC Films and formerly at InDigEnt, won through. “I never got any grief about it from the top of the organisation,” he says.

When a long casting call for the role of the protagonist Mason landed unknown Austin child actor Ellar Coltrane the role of a lifetime, Linklater knew the gods of film-making were smiling on him. “It really was a tribute to Rick and the loyalty he inspires, and his judgment,” Sloss says of Linklater’s approach. “When he was casting Ellar, he was also casting his parents. He knew his parents and had confidence they were going to show up every year and be responsible. That was the wild card, because the [on-screen] daughter is Rick’s daughter [Lorelei Linklater], anybody who knows Patricia knows she’s a stand-up person and we started this film before they conceived Before Sunset [the 2004 middle episode in the Before series], and Rick and Ethan had a very strong bond by then.”

It was time to map out the production. “Ultimately it’s 12 years, 12 scripts, 12 productions,” says the director, who sent a rough outline to IFC that he would update each year. “Within that it had quite a structure. I knew the last shot.”

Boyhood’s small budget dictated the nature of the locations. “I wanted to keep it local,” says Linklater. “We didn’t have enough money to fly people around.” And so Mason’s coming-of-age would play out against an array of Texan locales that included Austin, Houston and San Marcos.

Texas scenery meant Texas laws. Sloss did his due diligence on what was permissible in the actors’ contracts. Coltrane signed successive deals lasting seven and five years. Production on what was known at the time as The Twelve-Year Project got under way in July 2002 when Coltrane was seven. By the time shooting wrapped at the Big Bend Ranch State Park in West Texas in October 2013, they had filmed for 49 days in total and Coltrane was 18.

Time-sensitive

Bringing everybody together each year for three or four days of shooting was a logistical challenge.

“We would finish one year and talk about the possibilities for when we could get back together again,” says Cathleen Sutherland, an Austin native who came on board in the second year to produce with Linklater, Sloss and Sehring.

“People think we had this set date every summer. It wasn’t like that. It had to shift because Ethan was in a movie or doing a play, Patricia was in Medium, Rick had things going on. The kids were the easiest ones, with the rest of us trying to juggle life and responsibilities.”

Sutherland adds: “There were times when I could put my brain on cruise control. If I knew we were planning something a year out I could start to gear up when I needed to. Then things changed and somebody’s schedule changed and we had to play it by ear. One year somebody’s schedule changed and we jumped into that window six weeks out.”

Linklater would stay in touch with his actors throughout the year and often found the reunions quite seamless. “It’s a little bit like running into an old friend you haven’t seen in a while,” he says.

“It didn’t always work out that every crew member came back but for the most part people tried to repeat the job,” adds Sutherland. “It became a very close community. By the end of the film there was the 10-Year Club. It was great having that commitment from people.” As Coltrane says: “When you work on an art project with people for any amount of time, you become like family.”

Some of the senior personnel who became fixtures on the decade-plus journey alongside Linklater and casting director Beth Sepko included editor Sandra Adair, first AD Vince Palmo Jr, script supervisor Brooke Satrazemis, production designer Rodney Becker, make-up Darylin Nagy, costume Kari Perkins, set decorator Melanie Ferguson and grip Joe Vasquez.

As the production proceeded, Sloss mostly stayed away from the set. “Ultimately a Richard Linklater film is a Richard Linklater film,” he says. “He collaborated with his cast and I made suggestions, but he’s looking to us to give him the resources and protect him and get the film out.”

Sehring was of the same mind. “The whole production is unlike any other production in the world,” says Sloss, who was also busy running Cinetic Media. “I didn’t go to see it; it’s better I wasn’t on set. He had a great crew and people he surrounds himself with, and that’s how Rick works.

“He is so different; I don’t know any production that shot two to three days a year over a 12-year period. People ask why I wasn’t on set but honestly, what was I going to do?”

Touching moments

Hawke describes the making of Boyhood as “a triumph of patience and scheduling”. Like the events in the story itself, the production glided along without major drama. It was the little things that registered.

“Watching certain scenes touched on my life,” says Sutherland. “The scene with the bully in the bathroom was at the same junior high school where I went. The high school we shot in was where I graduated.”

Yet the undertaking inevitably fed into a collective sense of growing accomplishment that had a big impact on everyone involved.

Linklater recalls there being a build-up of tension that he had not anticipated. “Starting out, I thought it would maybe feel like an obligation. The first half of the movie was almost abstract because the end was so far away. But it really built and people got more invested in it. Everybody felt that way.”

By the time the finishing line was in sight, Linklater and Sutherland were zipping around, scouting for the final location for the scene in which Mason, now a college student, enjoys a trip out with new friends.

“Rick and I had scouted Big Bend National Park the month before and spent a few days in the car because it’s so big,” says Sutherland. “We were full-steam ahead with the park and we had come back to Austin and somebody said to me, ‘What about the government shutdown?’”

From October 1-16, 2013, the US federal shutdown went into effect following a Congressional impasse on funding legislation for the upcoming financial year. Government operations were put on hold and national park gates were closed.

“Everybody got kicked out of the park. This was a couple of days before we were getting ready to go there. So we called the Big Bend Ranch State Park, where we ended up shooting, and they were great. It’s wilder terrain. We hadn’t scouted anything there but we got out there.”

The resulting scene, framed within the light of the retreating sun, seemed like a fitting finale.

“It was an odd feeling to get to the end,” says Sutherland. “We were in a perfect place. The story had brought us out to west Texas for that last scene when they sit looking out at the sunset; that was the last scene we shot with the cast there.

“It was a great moment. It was the end of the process. It helped the crew and us. It felt right for us to be there and to finish strong.”

For Linklater, it was an unprecedented moment. “The last shot of [each] day had an intensity. Twelve years of that and when the sun goes down and it’s the last shot, you can imagine the intensity. I have never experienced anything like it.”

Patience of saints

Sehring was one of only four people who had seen the rough cuts each year alongside Linklater, Sloss and Hawke, likening the experience to “looking at a family album that you know you love, but you have no idea what anybody else is going to think”.

When the time came for the first internal IFC screening in late 2013, Sehring knew they had passed the first acid test. “Two people were crying at the end, so I thought that was good.”

Boyhood premiered in Sundance 2014 after it was dropped into the schedule late in the day. The response was euphoric. “I have been doing this for 30 years,” says Sloss, “and I have never come close to the notices.”

Although this was an IFC production, the plan in Park City was always to go in with open eyes. “If somebody had made us an offer we could not refuse, we would have sold it,” says Sehring, who wound up distributing Boyhood.

Everyone loved the film. Critics and audiences were in raptures. However, at two hours and 40 minutes, admiring distributors were concerned about playability. The following month Boyhood travelled to Berlin for its international premiere and Link-later won the Silver Bear for best director.

A deal was struck at Sundance with Universal for international rights excluding Canada (Mongrel), France (Diaphana) and Benelux (Lumiere), and after more international festival kudos the film opened in July in the US. By mid-November the audacious $4m experiment that had seemed so risky had amassed more than $23m Stateside and around $50m worldwide.

Sloss calls Boyhood one the “great privileges” of his career. Sehring says the whole package has turned a profit and admits to a deep personal attachment. “It’s a project that nobody really wanted to let go of or share. It was a big secret,” Sehring says.

“People would ask about the Richard Link-later ‘Twelve-Year Secret’. Fans would ask about it and it took on a mythology of its own. Did it really exist? It was like a family secret you don’t want to share.

“Everybody’s melancholic about it [being over]. People ask about the sequel and we laugh and it becomes less humorous and we miss it. Never say ‘never’, even though everybody said ‘never’ at the outset.”

If it ever happens, a return to the world of Mason and his family could take several forms. Sutherland, who is compiling a book of pictures about the film, may already have had a premonition.

“I had this strange dream,” she says. “We were producing Boyhood: The Musical.”

No comments yet