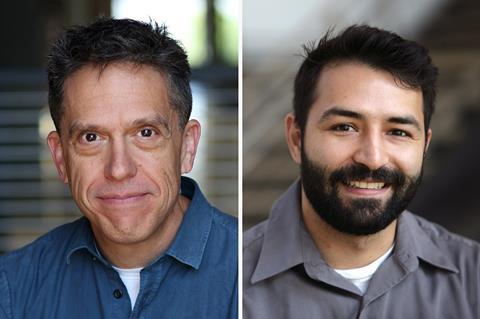

Pixar fields another strong awards contender with the acclaimed Coco, set against the Mexican tradition of the Day of the Dead. Screen talks to the film’s creative duo Lee Unkrich and Adrian Molina.

Director Lee Unkrich has been a steady force at Pixar, having worked as a co-director on Toy Story 2, Monsters, Inc and Finding Nemo, as well as directing 2010’s Toy Story 3, which grossed more than $1bn worldwide. As work on the latter wrapped up, Unkrich began to develop a few ideas around what he wanted to do next. “One of them was the notion of telling a story set against the Mexican tradition of Dia de Muertos [Day of the Dead]. I’d always been interested in the celebration, mostly through the folk art and iconography of the tradition,” says Unkrich.

As he delved into the subject matter, he began to realise how family-centric the tradition is. Unkrich pitched the story to Pixar’s chief creative officer John Lasseter in September 2011, seeing the filmic potential behind the longstanding Mexican celebrations that focus on the gathering of family and friends to remember deceased loved ones. Lasseter was on board in short order.

Unkrich and his team spent the first three-and-a-half to four years of the film’s development working on the story and the screenplay, and visually exploring the look of the world and characters. The actual animation of the film took place in the final year-and-a-half of production. Coco’s co-director Adrian Molina, who is Mexican-American, came on board the project about three years into its development, initially as one of Unkrich’s storyboard artists (he also worked on Toy Story 3 in the same capacity). After realising the production was facing serious story problems, Molina took a bold risk and offered up his own solutions, in script form, to Unkrich.

“Hopefully it doesn’t seem complex when you watch it, but there’s a lot of moving pieces to the story and a lot of those took a long time to figure out,” explains Molina. “I would take those problems home with me and try to come up with solutions, kind of unsolicited. I wrote script pages, and very soon after Lee read them, I [did] a whole treatment for the outline, and wrote a full version of the script a few years into production.”

Molina, who started at Pixar in 2006 as an intern, was upped to co-director status just under two years ago. Unkrich, Molina and the entire team at Pixar took on the challenge of making the film as authentic and respectful to the Mexican culture as possible. In what was the first of many trips, Unkrich and his team travelled to Mexico to observe and embed themselves with local families during the multi-day celebration. “[The families] brought us into their homes and showed us their livelihoods,” says Unkrich. “They fed us and shared their traditions around Dia de Muertos with us. I just felt like being embedded with real families was going to help keep our story very grounded.”

The research process was exhaustive. Unkrich’s team took tens of thousands of photographs of Mexican architecture, and details of different towns that they visited in order to reproduce them for the film. Research extended not only to being in Mexico, but to people the team surrounded themselves with at Pixar, with a number of Mexican and Mexican-American crew members as well as three key cultural advisers: Octavio Solis, Marcella Davison Aviles and Lalo Alcaraz. “The three of them formed our core group,” notes Unkrich. “We let them behind the curtain in a way that we never had let outsiders into our process at Pixar.”

The advisers were present at every pitch and screening of the film, as well as being heavily involved in decisions pertaining to marketing and merchandising. “We also brought in luminaries from the Latino community to look at the film on occasion and weigh in; everyone from artists, to politicians, to media executives,” Unkrich adds. Molina also used his own family and personal history as a narrative and character resource.

Unkrich initially planned for the story to be told from an outsider’s perspective. However, the intense research brought a level of comfort and confidence that they could effectively tell the story from within the Mexican culture. Once that was decided, the idea of making music central to the story came to the forefront — with a little inspiration from the Coen brothers. “I envisioned it at a certain point as being like the Coens’ O Brother, Where Art Thou?,” says Unkrich. “It’s a film that really embraces music being in the DNA of the story, without it being a traditional Broadway ‘break out into song’ musical. I wanted to do the same with Coco.”

Note perfect

To ensure the film reflected Mexico’s diverse musical landscape, Unkrich and Molina hired music consultant Camilo Lara, creator of musical group Mexican Institute of Sound. They also recruited Disney’s Frozen songwriters, Bobby Lopez and Kristen Anderson-Lopez, to write their film’s signature song ‘Remember Me’, which Unkrich calls “the bedrock of the story”. Michael Giacchino, who has scored several Pixar films, served as Coco’s composer. Unkrich partnered him with Mexican-American composer Germaine Franco, who helped Giacchino with some of the orchestration and arrangements to make sure everything stayed quintessentially Mexican. Molina even contributed to the music of the film, writing a number of songs with Franco.

Unkrich explains that casting on an animated film can be a tricky prospect, particularly when the lead character is a pre-teen, as is the case with 12-year-old protagonist Miguel, who is descended from a family of shoe-makers but dreams of becoming a musician. “Movies do take a long time to make, so I didn’t want to run the risk of his voice changing in the middle of us making the movie,” says the director. “We had to find a kid that was on the young side, but could still act and sing and have the maturity to be able to work on a film like this, and luckily we found Anthony Gonzalez who ticked every box.”

Gael Garcia Bernal voices the character of Hector, a charming conman Miguel meets in the Land of the Dead. Molina notes that Bernal was instrumental in shaping the character: “[Hector] took a little bit of discovering. He went through a few iterations, before we even started looking at actors. In our very first recording session, [Bernal] brought this energy and off-kilter quality that really helped to inform Hector and make him as well-rounded as he is in the film.”

When Unkrich set out to make Coco, his ultimate goal was to screen the movie in Mexico and for it not to feel like it was made by outsiders. Coco premiered at Morelia International Film Festival on October 20, and it went on to beat Marvel’s The Avengers to become the number one film of all time in Mexico after just 19 days of release (at time of press it had taken $50.2m). “Based on the reception, I think we’ve managed to pull it off,” Unkrich says. Coco opened in the US on November 22, and will have rolled out across most major territories by the end of January (including a January 19 release in the UK).

“My hope with this film,” says Molina, “is that it does for knowing your personal story what Inside Out did for talking about your emotions, or what Toy Story did for finding that love and attachment to childhood. Thus far it has been very encouraging to hear people’s reactions to it.”

Life and death creating Coco’s two worlds

Coco features two vastly different worlds, the Land of the Living and the Land of the Dead. The Land of the Living, the fictional town of Santa Cecilia where Miguel lives, is based on the small towns that Unkrich visited in Mexico. “A town called Santa Fe de la Laguna ended up being a big visual touchstone for us,” he says.

In conceptualising the afterlife, Coco’s makers utilised the city of Guanajuato as the visual starting point. “I didn’t want it to be an anything-goes fantasy world,” the director continues. “I wanted it to still be rooted in the Mexican culture. Guanajuato is this beautiful city that’s encrusted into a hillside. It’s full of colourful buildings that are all stacked one upon another.”

The team also wanted to have a sense of Mexican history. Various types of architecture are represented in the Land of the Dead, because people have been dying over time. “We envisioned these big towers that start down at their base with Aztec pyramids, and as they grow up over time you see different eras of Mexican architecture, all the way to the most modern at the top,” he says.

A unique visual element incorporated into the Land of the Dead is that of the spirit animals, which Unkrich based on a type of Mexican folk art called alebrijes. “You see them all over the place in Mexico, but mostly in Oaxaca,” he says. “They don’t have anything to do with Dia de Muertos, to the traditions specifically, but they are such a big part of Mexican culture that I wanted to find a way to make them part of the film.”

No comments yet