In 2002, Bait writer/director Mark Jenkin was living in London, cutting trailers for movies on Channel 5, when he was offered a promotion. “It scared the shit out of me, because I thought, ‘If I take this, I’m going to be in this company forever,’” he recalls, speaking a few days before Cannes. “It was always a stop-gap. I wanted to learn how to edit, I wanted to be in London for a while. I also realised I wasn’t working in the film industry, I was working in marketing. The next day, I handed in my notice and moved back to Cornwall.”

Jenkin worked several jobs, mostly on building sites, while he honed his craft making shorts and documentaries, and began writing what, 17 years later, would become Bait. Shot in grainy 16mm black and white using a clockwork Bolex, with post-synch dialogue and sound, and a minimal crew, Jenkin’s breakthrough Cornish fishing drama was a revelation, premiering at the Berlinale and winning him a Bafta in 2020 as well as huge critical praise. “I became an overnight success, but it had been 20 years in the planning and some pretty tough times,” he says.

Post-Bait, Jenkin was offered more conventional, bigger-budget projects, but turned them down in favour of returning to his roots, although he does not rule out doing something larger in future. “My agent said, ‘What do you want to do next?’ We agreed the best thing was to go quickly on another small film, and kind of repeat what we had done, not in terms of subject matter, but in terms of scale,” he says.

Enys Men, which screens in Directors’ Fortnight today (May 20), is another haunting, handmade tale: a Cornish folk horror inspired partly by the standing stones he sees every day, partly by audience reaction to Bait.

“More and more people mentioned this sense of the uncanny, of foreboding and dread within Bait and the [short] I did before, Bronco’s House, that it was almost tipping into horror,” he says. “So I thought, ‘I’m going to write a horror.’ I wrote it quickly, in three nights, in a frenzy, then typed it up, and read it back. I said, ‘Oh great, I’ve written a horror film [but] there’s no horror in this.’ That is when I realised the horror is in the form; it’s the film that’s uncanny rather than the content. I thought I was going to make a more conventional horror film, but I’ve made something that’s a little less conventional.”

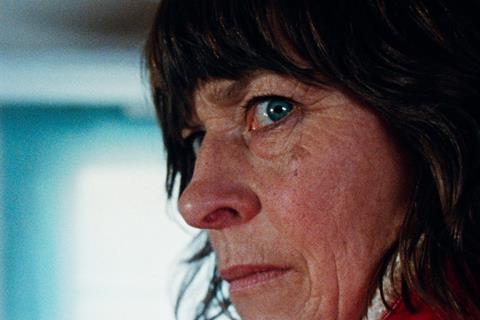

Set in 1973, Enys Men stars Mary Woodvine, Jenkin’s real-life partner, as The Volunteer, who lives alone on a remote Cornish island monitoring a rare flower that grows on the cliff by an abandoned tin mine. But as the days stretch into weeks, she begins to experience a series of vivid, unsettling visions as the island’s past catches up with her.

Stripped-back filming

Financed by Film4, Falmouth University’s Sound/Image Cinema Lab, the Mining Heritage Trust and a couple of private investors, Enys Men utilises the same production process and camera as Bait, albeit with a couple more lenses. “I used a zoom lens a lot to nod towards those 1970s horror films,” says Jenkin, who filmed for 21 days on location near Penwith, where he lives. “It’s mostly moorland west of me, so we were able to shoot a lot of isolated, island-like shots out there.”

The core crew numbered around 10. “There’s no sound department, so that shrinks everything down. If I’m out on location, it could be me, Mary, Colin Holt, who lights with me, and Callum [Mitchell] my first AD. We don’t have any video village. We haven’t a preview monitor. It’s just me looking down the viewfinder. I only shoot one take and, normally, a safety. I don’t shoot coverage. I shoot the film I see in my head.”

On Bait, in addition to filming, editing, doing the post sound, foley and music, Jenkin also processed the negative himself. Because Enys Men was shot in colour, he decided to have it developed in a lab, but was concerned the negative would be too clean, without the imperfections — scratches, light flares, grain — that made his previous work unique.

“I did worry, ‘How am I going to interfere with the film?’” he admits. “What we ended up doing was pushing the neg. We would be out on the moor with a single light source, take a meter reading and then I would underexpose maybe three stops.

“It was risky, but I was able to push it later, and the image begins to fall apart, and the grain comes out. I like what grain does to human faces, what it does to landscape.”

No comments yet