A year after Honeyland snagged two Oscar nominations, a number of high-profile documentaries have set their sights on the international film category.

It is being called the ‘Honeyland effect’. Last year, an unsung North Macedonian documentary about a woman who keeps wild bees in the mountains won multiple awards. It played at some 40 festivals and secured two Oscar nominations — for best international feature and best documentary feature.

The directors Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov were little known, the budget was small and the film was not in English. In previous years, such a title would have struggled to make any impact with US audiences. Now, though, thanks to the rise of the streamers and of adventurous exhibitors such as Neon (which released Honeyland), foreign-language documentaries are establishing a foothold in the North American market. Netflix confirmed recently that viewing of foreign-language content by US viewers had risen by 50% in 2020.

The list of films chosen to compete for this year’s international feature film Academy Award (known until 2019 as best foreign-language film) includes a healthy representation of documentaries. Alexander Nanau’s Collective is the Romanian entry; Gianfranco Rosi is in the hunt for Italy with Notturno; Barbara Paz’s Babenco: Tell Me When I Die is from Brazil; Maite Alberdi’s The Mole Agent has been submitted by Chile; Anabel Rodriguez Rios’s Once Upon A Time In Venezuela is the Venezuelan candidate; Kenya has selected Maia Lekow and Christopher King’s The Letter; and Luxembourg put forward Julie Schroell’s Nicaragua-set River Tales.

This tally of seven documentaries submitted to the Oscars category matches that of last year — both down one from 2019’s total of eight submissions but a healthy rise on the five submitted for 2017 and three for 2018. Perhaps more pertinently, the documentaries this year have all screened widely on the festival circuit and most have powerful sales agents and distributors behind them. Collective, for example, was acquired by Magnolia Pictures and Participant Media, while Notturno is being released in the US by Super Ltd, Neon’s boutique label.

“Documentaries have reached a critical mass not only in the US but in Europe and it seems like globally as well,” says David Piperni, president of New York-based sales agent Cargo Film & Releasing, which is handling sales on Once Upon A Time In Venezuela alongside Berlin’s Rise & Shine. “The streamers have a space for documentary films and have shown that if you make the films available, viewers will watch them. What we are seeing now with the number of countries submitting documentary films as their candidate [for Academy Awards] is a continuation of that trend.”

Once Upon A Time In Venezuela, which premiered last year at Sundance, explores the plight of a small fishing village in Venezuela whose future is threatened both by political corruption and by climate change. It is the first Venezuelan documentary to be selected as the country’s international feature Oscar contender. “I don’t believe 10 years ago, there would have been space for this kind of scenario,” suggests Piperni.

A campaign that travels

Chile has achieved significant awards success in recent years with dramatic features such as Sebastian Lelio’s 2018 Oscar winner A Fantastic Woman and Pablo Larrain’s 2013 Oscar nominee No. Why then choose a documentary as this year’s Oscar candidate?

“It’s not because we don’t have strong fiction this year but it is really [about] the quality of The Mole Agent,” says CinemaChile executive director Constanza Arena of Maite Alberdi’s crowdpleaser about an elderly private investigator going undercover in a retirement home. “People adore her films and the way she picks characters.” The Mole Agent, sold internationally by Dogwoof, was released on VoD in the US through Gravitas Ventures.

Alberdi is predicting a more open contest than in previous years, both because of changes in the membership of the academy and because of Covid-19. “We are trying to define a campaign that will reach more people seeing the film in different places,” she says. “The academy now has more diversity and there are members all over the world.”

The director argues the pandemic ought to make campaigning more democratic: “You don’t have to do those screenings that have very high budgets in LA, New York and the UK, where you spend the money on cocktails.”

Oscar winner Lelio is getting behind The Mole Agent’s run and has hosted a Q&A with Alberdi. Her campaign is building on what has already been achieved by companies such as Fabula Films, the outfit behind A Fantastic Woman, No and Jackie, and by the team behind Bear Story, the animated short that won a first ever Oscar for Chile in 2016.

“They make you dream more than before,” Alberdi says of how The Mole Agent is benefiting from past Chilean successes. It helps, too, that she has the backing of a state-funded international promotion agency like CinemaChile.

Barbara Paz, director of Brazil’s Oscar entry Babenco: Tell Me When I Die, is not receiving the same level of support. The country’s right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro has cut arts funding, and state film body Ancine has withdrawn financial support for promoting Brazilian films internationally. “Every year, the Brazilian government helps films that are going to run in the Oscars,” says Paz. “This year I haven’t received anything, not even a note of congratulation.”

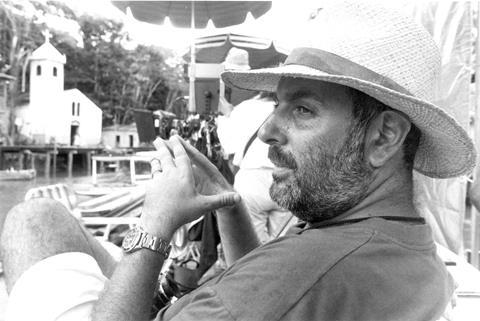

Even so, Paz — a high-profile actress in Brazil as well as a producer and director — is campaigning hard. Her film, an award winner at Venice in 2019, is an impressionistic and poetic piece about the life and work of her husband Hector Babenco, who died in 2016.

Argentina-born but one of the most revered figures in Brazilian cinema history, Babenco’s credits include Pixote and Kiss Of The Spider Woman. Paz’s documentary is executive produced by Willem Dafoe, who starred alongside Paz in Babenco’s autobiographical final feature My Hindu Friend (2015). “It is a love letter to cinema,” Paz says of her film. “You’d have to ask the jury why they chose it [as an Oscar contender]. There were many good [dramatic] movies running [but] this one touches people’s hearts… and people are looking more for reality than fiction these days.”

For Julie Schroell, the director of Luxembourg’s contender River Tales, being chosen was a welcome relief after what had been a difficult journey. “It was very surprising. I didn’t even know it was actually possible,” she says of the selection of a documentary to run for the award.

River Tales’ national premiere, set for mid-March at Luxembourg City Film Festival, was abandoned because of the coronavirus lockdown. Although the picture screened successfully at various virtual festivals — and won a prize at Galway Film Fleadh — its international rollout was badly affected. “At the end of all this, then came the Oscar [campaign] and suddenly people were much more aware of it,” says Schroell.

An open field

In the past, the best international feature film Academy Award category resembled a horse race in which a number of outsiders enter hoping for a fluke win. Documentaries were rarely even in contention. With the notable exception of Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture (Cambodia) in 2013, in the past 20 years not a single doc secured a nomination before Honeyland. However, those behind the documentaries vying for the international Oscar this year all believe they have a chance of success.

Because of the pandemic, smaller titles can compete when it comes to organising virtual screenings and Q&As that might have been beyond their budgets as physical events. The streamers have shown that a US audience exists for non-English language documentary. And thanks to changes at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the drive to increase the scope and diversity of its international voting membership, documentary features have become a more significant part of the awards conversation than ever.

No comments yet