Sergei Loznitza turns his gaze to wartime Ukraine, and the 1941 massacre of Jews outsite Kiev, in this powerful documentary

Dir: Sergei Loznitsa. Netherlands, Ukraine. 2021. 121 mins

With his 2016 documentary Austerlitz, Sergei Loznitza reflected on the appalling contemporary phenomenon of Holocaust tourism, observing concentration camp visitors uninterested in engaging with the terrible history under their feet. So Babi Yar. Context unavoidably feels like a companion piece, which draws upon extraordinary archive footage to peer directly into the darkness. The subject here is the WWII genocide of Ukraine’s Jewish population. Editing film and stills from state and public archives in Russia, Germany and Ukraine, some of it never seen before, Loznitsa creates a fascinating and quietly devastating chronicle of invasion, occupation and slaughter. As ever, the Ukrainian director doesn’t labour his film with voiceover or overt authorial steers. Yet this is close to home, and it’s impossible not to feel that he’s holding his country to account; for while this was a Nazi extermination, it came with a degree of collusion.

A chilling nonchalance in front of and behind the camera

The special screening in Cannes will likely be the precursor to further festival outings. The troubling rise of an xenophobic far-right in Europe and the film’s cautionary resonance may add to its chances of niche distribution.

The title refers to the Babi Yar ravine outside Kiev where, over two days in September 1941, SS soldiers aided by Ukrainian police shot 33,771 Jews, with no resistance from the local population. Though the addition of the word ‘context’ may seem rather dry and unnecessary, the intention it represents – situating the massacre within the entire period of Nazi occupation – is astute, revealing patterns of movement and behaviour between two oppressors and the citizens caught between them.

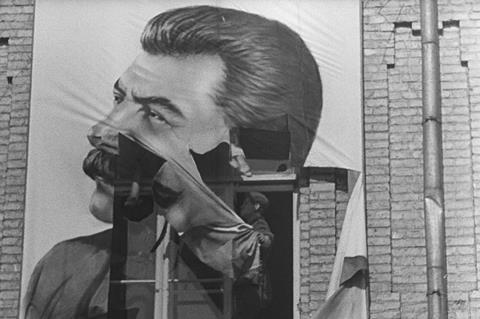

The film opens in June 1941, with explosions that mark the Soviets’ ’scorched earth’ policy as they retreat east. Loznitsa follows the German advance across the country. As they enter each new town or city, they are welcomed by locals happy to see the back of the Russians: soldiers are handed flowers, Stalin’s image is torn down, posters of Hitler the liberator are put up, children fight for Swastika flags.

But the Soviets’ parting gifts (the murder of prisoners in Lvov by the NKVD) and underground strikes (a series of bomb attacks in Kiev) led to Nazi retribution; or, more likely, the Russians created the excuse for something that was intended all along. Jews are accused of collaborating with the enemy, rounded up and murdered. The direction eventually returns westwards, as the Red Army retakes Ukraine. The Hitler posters come down, back comes Stalin, once again the locals cheer their liberators in a twisted sway of allegiance.

Along the way, Loznitsa and his team perform miracles with their material, some of which needed extensive restoration, the results witnessing a horrific, brutal, poignant reality: corpses strewn in a field in the aftermath of battle; soldiers destroying village homes with flame throwers, a faint sound in the background that could be the wind, or screams; Jews being beaten in city streets, in images that have a ghostly quality, as if Gerhard Richter’s photo-realist paintings have been animated.

The existence of many of these images is due to the fact that German soldiers brought amateur film cameras with them into war. This might explain, too, the chilling nonchalance both behind and in front of the lens.

The aftermath of Babi Yar is represented by a short series of stills, of massed corpses, discarded coats and shoes, a prosthetic leg. Later, a stunning sequence of photos shows a gathering of Jewish people in Lubny – the faces of young and old, thoughtful or scared, made all the more haunting because of what is about to happen to them.

As ever, Loznitsa doesn’t go out of his way to make clear what he’s showing, and supposition is sometimes required; his films aren’t delivered on a plate. In this instance, any ambiguity regarding perpetrators, prisoners, victims, simply adds to the sense of a collective loss of humanity.

There’s nothing ambiguous in the testimonies during the 1946 trials related to the atrocities (the cavernous hall, beams of light arrowing into the hushed audience, could have been shot by Gregg Toland), nor in the decision to show a lengthy, intensely moving extract from Vasily Grossman’s article, ’Ukraine without Jews’, in which the author declares: “In Ukraine there are no Jews. Nowhere”.

Production company: Atoms & Void. contact@atomsvoid.com

Producers: Sergei Loznitsa, Maria Choustova

Screenplay: Sergei Loznitsa

Editing: Sergei Loznitsa, Danielius Kokanauskis, Tomasz Wolski

No comments yet