Some sobering truths on how an American hero was treated during his own lifetime

Dir: Sam Pollard. US. 2020. 106mins.

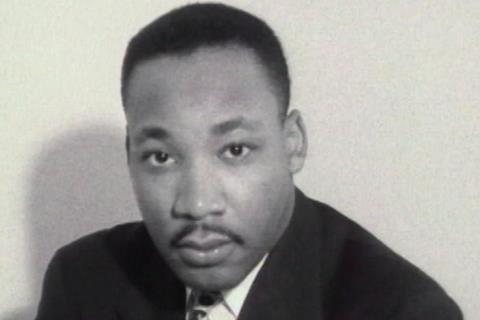

Fifty years after his murder, Martin Luther King Jr. is hailed as an American hero and champion of non-violent protest, but as MLK/FBI suggests, that wasn’t necessarily how he was viewed in his own time — especially by the government. Sam Pollard’s meticulous documentary makes good use of recently declassified files to study how the FBI targeted the civil-rights leader, determined to undermine his moral authority and personally embarrass him. The film isn’t particularly electric in its presentation, but it serves as a sombre reminder of how much white supremacy is woven into the country’s fabric — and also how relevant King’s causes remain today.

MLK/FBI explores the lengths that the bureau went to spy on the civil-rights leader

Screening as part of several North American fall film festivals, MLK/FBI will strike a chord as the Black Lives Matter movement gains visibility in the US. And considering the success of recent portraits like Selma and I Am Not Your Negro, this deep dive into King’s battle with racism — and FBI head J. Edgar Hoover — should prove popular with socially-conscious viewers.

Pollard (Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me) reconstructs King’s often fractious relationship with the US government, explaining why Hoover saw the activist as a danger to the nation. Drawing from archival footage, clips from fiction films that glorified the FBI, and interviews with scholars, MLK/FBI explores the lengths that the bureau went to spy on the civil-rights leader. Of special interest were King’s extramarital affairs, which Hoover hoped would demonstrate to the American people that this politically outspoken minister was nothing but a hypocrite.

More an important history lesson than riveting cinema, MLK/FBI can’t escape a certain dryness as it combs through surveillance reports. Unlike a documentary such as I Am Not Your Negro, which brought the late James Baldwin back to life through the power of his words and public statements, Pollard’s film doesn’t feature an enormous amount of clips of King himself. When he is shown, however, in clips from The Merv Griffin Show or Face The Nation — or when he receives his Nobel Peace Prize — it’s striking just how confident and composed this young man was, his calm charisma always evident.

But as the film’s title suggests, King is only part of this story, and Pollard spends a fair amount of time charting the development of the FBI — as well as the rise of Hoover, who led the intelligence agency for nearly 50 years. MLK/FBI makes a persuasive case that Hoover saw his job as preserving a specific kind of American life — a rigidly white, patriarchal one — and therefore hired men at the bureau who reflected that worldview. It was no surprise, then, that King’s ability to rally black (and many white) Americans to the cause of social justice and racial equality alarmed Hoover, who became obsessed with taking down the minister.

MLK/FBI incorporates several speakers — including Clarence Jones, who was friends with King, and Beverly Gage, a historian writing a book about Hoover — who provide crucial context, although Pollard intriguingly chooses not to feature them on screen, instead letting their voices serve as a soundtrack to accompany the visuals. Among those are clips from films like the 1959 Jimmy Stewart drama The FBI Story, and the documentary smartly illustrates how Hoover, as part of his propaganda campaign to boost the FBI’s image, recruited Hollywood to tell stories that depicted the so-called G-Men as protectors of the public good.

Right now, when black Americans are still being killed by white police officers, inspiring mass protests and a renewed cry to examine systemic racism in US institutions, MLK/FBI speaks to the opposition King faced in his lifetime — and not just from the FBI. Pollard deftly utilises news footage in which bigoted white Americans berate the activist for being a troublemaker. Even President Lyndon Johnson, who fought to enact civil-rights legislature that King spearheaded, eventually viewed King as an adversary once the minister denounced the Vietnam War, putting him in opposition with the president.

At its best, MLK/FBI connects the dots between then and now, arguing that the nation’s continued inability to grapple with its legacy of slavery perpetuates racial tension and inequality. The film may not always be dynamic, but its sober lesson couldn’t be clearer: it became much easier for some to honour King long after his death and when he was no longer a threat.

Production company: Tradecraft Films

US sales: Cinetic Media, sales@cineticmedia.com

Producer: Benjamin Hedin

Screenplay: Benjamin Hedin, Laura Tomaselli, based on the book The FBI And Martin Luther King, Jr.: From “Solo” To Memphis by David J. Garrow

Editing: Laura Tomaselli

Cinematography: Robert Chappell

Music: Gerald Clayton