Locarno’s post-production section has undergone a makeover this year, with a new name and a shift in regional focus.

Israeli cinema is the focus of Locarno Film Festival’s annual territory-focused work-in-progress showcase this year. Rebranded as First Look, from Carte Blanche, the strand will premiere six works in post-production to industry professionals, with the onus on sales agents and festival programmers.

First Look on Israeli Cinema will be Locarno’s fifth work-in-progress event, following editions devoted to the cinema of Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico.

“After focusing on Latin America, we decided to shift our attention to another region. Israeli cinema is of an excellent quality and regularly gets picked up for international distribution,” says Locarno industry head Nadia Dresti, who oversees the initiative alongside project manager Markus Duffner.

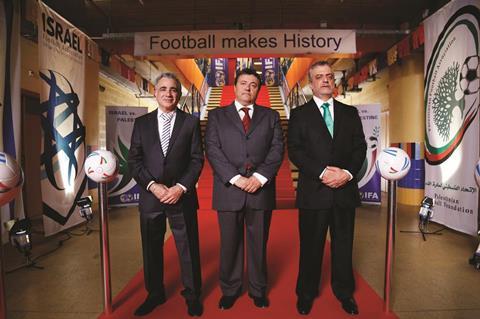

As to be expected from a territory as complex as Israel, the selection offers diverse stories and styles. It includes Eyal Halfon’s satirical mockumentary The 90 Minute War in which Israeli and Palestinian leaders decide to settle the Middle East conflict on the football pitch.

Assaf Amir of Norma Productions, whose credits include Fill The Void and Broken Wings, is co-producing alongside Germany’s Gringo Films, which also has experience in the Middle East having worked on Yuval Adler’s award-winning feature Bethlehem.

In a different vein, Eitan Anner’s drama A Quiet Heart explores the growing strength of the ultra-orthodox movement in Jerusalem through the tale of a secular concert pianist, played by Ania Bukstein, who moves to the city from Tel Aviv. Green Productions, which produced Tom Shoval’s Youth and is working on his next feature Shake Your Cares Away, is the lead producer on the film.

“Locarno is an amazing platform. Everyone will be there,” says company co-founder Gal Greenspan, who will be in attendance.

In another contemporary tale, Meni Yaesh’s Our Father revolves around a tough Tel Aviv nightclub bouncer who tries to extricate himself from a debt-collection racket. It is Yaesh’s first film since his award-winning God’s Neighbours, which premiered in Critics’ Week at Cannes in 2012.

Veteran producer Marek Rozenbaum of Transfax Film Productions is producing.

In Haim Tabakman’s Ewa, an elderly man discovers his wife of decades, a Holocaust survivor, has been hiding their joint ownership of a property he did not know existed. Producer David Silber of Metro Communications, whose credits include Hannah Arendt and Lebanon, will accompany the work.

In another tale that hinges on an untold secret, Miya Hatav’s Hope (Amal) follows Bina, an ultra-orthodox woman who bonds with a young woman when visiting her estranged son in hospital after a stabbing. Unbeknown to Bina, the young woman is Palestinian and also her son’s lover. Producer Elad Peleg will be in Locarno with the rough cut. His company Daroma Productions, based in the southern Israeli town of Sderot, focuses on minority voices not always heard in the mainstream media. His credits include Red Leaves, which was set within Israel’s ethnic Ethiopian community.

The sixth rough cut is Elite Zexer’s drama Sand Storm about a Bedouin mother and daughter testing the limits of their conservative community.

“There’s a strong appetite for Israeli films from buyers. We’re confident there’s going to be a good attendance at the event,” says Dresti.

Courting controversy

Locarno’s choice of Israel has not met unanimous approval. More than 200 directors and producers signed a petition last April calling on the festival to drop the focus as part of a cultural boycott of Israel to protest its ongoing occupation of Palestinian territories.

Locarno, however, decided to press on with the planned focus, in the name of “freedom of expression” and “artistic liberty”, and in the hope that the event will be an opportunity for debate and dialogue. “We’re happy to be welcoming Israeli film-makers and giving them an opportunity to show their films,” says Dresti.

The protest petition, however, did prompt one change. It was the catalyst for the renaming of the initiative to First Look from Carte Blanche.

“We decided ‘Carte Blanche’ could be misconstrued and gave the impression that somehow the chosen territory had free reign over the festival, which isn’t the case,” says Dresti.

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

No comments yet