Dir: Alex Gibney. US. 2014. 120mins

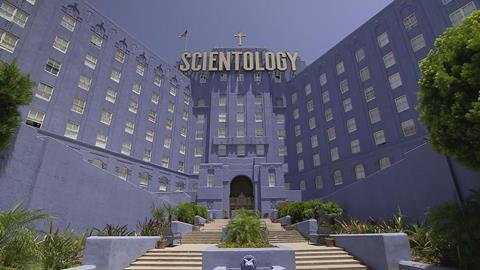

If Paul Thomas Andersons’ The Master presented an evocative fictional story inspired by Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, muckraking documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney offers this harrowing real-life counterpart: a searing exposé that reveals Scientology’s merciless ways. Gibney’s best work since the Catholic Church sex abuse film Mea Maxima Culpa, Going Clear lays out a lucid argument against the organization, combining engaging interviews, archival footage and evocative visual illustrations.

The cumulative effect is a serious, strange and unsettling account of brainwashing, greed and gross misuses of power.

Given Scientology is a worldwide phenomenon, known for its famous Alpha-male practitioners John Travolta and Tom Cruise, this slick and alarming HBO-produced documentary could make modest commercial inroads in international markets after its US cable TV premiere in March.

Based on the book Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, & the Prison of Belief by Pulitzer Prize-winning authorLawrence Wright, the film examines several facets of the “religion,” beginning with an examination of L. Ron Hubbard himself, then charting the evolution of Scientology from a cult phenomenon to a highly secretive, dangerously protective and “rapacious” billionaire-dollar industry.

When seeing archival footage of Hubbard, it’s easy to see where Philip Seymour Hoffman derived his magnetic performance in The Master: Hubbard, with orange-hair and a big smile, revealing yellowish teeth, comes across as arrogant and buoyantly egomaniacal. His few recorded interviews suggest a man on the edge of insanity. “Are you mad?” asks one interviewer. And Hubbard doesn’t deny it: “The only mad man is the one who doesn’t think he’s mad,” he replies with a smirk.

Gibney also introduces the key technological instrument of Scientology: the “E-Meter,” a machine similar to a lie detector, which Scientologists employ in “auditing sessions.” The “E-Meter” becomes a tool in which emotional traumas are monitored, discussed and eventually “discharged.” After many such sessions, practitioners aspire to a point where they are “clear” of such inhibitions; hence the film’s title, “Going Clear.”

Interspersed with Hubbard’s rise to fame, the film includes several revealing interviews with ex-members, including, most notably, director Paul Haggis (Crash), who remained in the Church for 35 years. Haggis’ candid testimony offers startling evidence of how a perfectly intelligent person could be completely duped—to a point.

One of the most outrageous features of Scientology, we learn, is only revealed to practitioners after many years—and dollars—into the programme, involving a wild sci-fi story about “Xenu,” a Galactic Overlord, who dropped people into volcanoes 75 million years ago. The story affords Gibney and his team a wonderful visual opportunity, which they take up with aplomb, creating a delightfully psychedelic montage that combines layers of archival animation and stock footage. It also effectively confirms Scientology’s loopy ambitions. As Haggis says, “I’m down with the self-help stuff, but what the fuck is this?”

After Hubbard’s death, the film focuses on Scientology’s second-in-command, Scientology lifer David Miscavige, an apparently power hungry abusive leader. The story details his greatest triumph—establishing tax-exempt status for the Church of Scientology—as well as his most egregious tactics to stay in power.

Another bravura montage details a surreal scene in which several high-ranking members were forced to live entrapped in a doublewide trailer called “The Hole,” and instructed by Miscavige to play a game of musical chairs to the Queen song Bohemian Rhapsody. Only the last man standing would be allowed to stay in the church. Gibney goes all out, showing folding chairs flying through space.

As the film goes on, it paints an increasingly severe portrait of Scientology, addressing the harmful ways it treats its critics, its former members, and even those within the Church. One Hollywood publicist describes how she was detained within the Church’s Rehabilitation Project Force, essentially a prison reeducation camp, where members must do hard labor.

Scandalmongers will pay special attention to the film’s section on Tom Cruise, where several former members testify that the Church instigated and exacerbated Cruise’s breakup with Nicole Kidman, who was considered a “Suppressive Person.” But the most affecting scenes show how regular devoted families were torn apart and pitted against each other as a result of the paranoid and destructive nature of the Church.

Gibney’s aesthetic tactics don’t always work; some reenactments are heavy-handed or sensationalistic. But the feature film, at two hours, remains more persuasive and tightly conceived than Gibney’s previous films Wikileaks: We Steal Secrets and The Armstrong Lie. Editor Andy Grieve (Manda Bala, Standard Operating Procedure) pulls together several excellent sequences, and Will Bates’s mystical-sounding original music, dominated by the otherworldly sounds of the Theremin, provides an apt soundtrack for the proceedings. The cumulative effect is a serious, strange and unsettling account of brainwashing, greed and gross misuses of power.

Production Company: Jigsaw, HBO Documentary Films

International Sales: Content Media, www.contentmediacorp.com

Executive producer: Sheila Nevins

Producers: Alex Gibney, Lawrence Wright, Kristen Vaurio

Cinematography: Sam Painter

Editor: Andy Grieve

Music: Will Bates