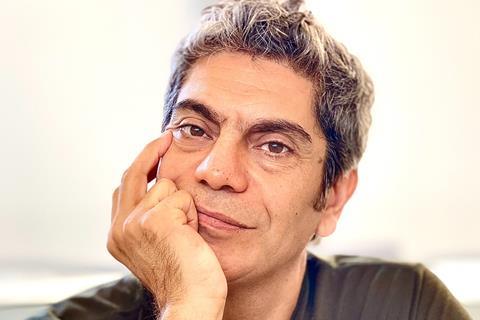

Lebanese writer and director’s Michel Kammoun’s second feature Beirut Hold’em uses gambling to frame the lives of the urban poor in his native city of Beirut, with the title taking its name from a popular local card game.

The film is making its world premiere at this week’s inaugural edition of the Red Sea International Film Festival, among nine titles showing in the Arab Spectacular, one of the festival’s 11 programmes.

Palestinian actor Saleh Bakri stars as a small-time gambler in his 40s, struggling to rebuild his life after a few years in prison. The story joins him as he arrives back in Beirut, where he finds his family fractured by his younger brother’s death, his girlfriend preparing to emigrate, and all his money stolen. When he is not scraping together cash, he hangs out with his three boyhood friends, a mechanic, a jockey; and a wheeler-dealer, who makes a living through sometimes-shady business deals.

Beirut Hold’em was conceived in the pre-Covid era, though production was interrupted by pandemic and the crises that have hit Lebanon since late 2019, from the country’s interminable economic and financial collapse to the deadly ammonium nitrate blast that devasted Beirut in August 2020.

“It’s difficult making films in this country,” says Kammoun. “This one was a particularly difficult. It was ambitious and a bit complicated to make, production-wise. Funding is always a problem, but of course any filmmaker could tell you the same.”

Kammoun’s award-winning 2006 debut feature Falafel was explored the lives of Lebanon’s lower middle class, struggling to retain respectability in a chaotic, at times seedy circumstances.

Of Beirut Hold’’em, he says: “I became a bit haunted by the story of this guy, trying to rebuild his life after losing everything. I started to think about how many chances we get in life. Do you have the right to a second chance? What can you rely on, when nothing is sure, when you’re living in a society where you’re forced to gamble on your own future?

“[He] wants to build something solid for himself, to be able stay in his country, but he has to live through one last period of loss before he can start over again. Through him we see the struggling classes, which unfortunately is now the story of most people nowadays. But for me these are never tragic stories. They’re stories of life going on.”

Funding the film

Shooting for Beirut Hold’em got underway against the backdrop of the struggling national economy, giving lead producer Sabine Sidawi of Beirut-based production house Orjouane Productions, and its Lebanese co-producer Abbout Productions, a challenge when it came to raising the budget.

According to Sidawi, the film was backed by Orjouane Productions, Roy Films, Doha Film Institute, Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, Fond Francophone, Arab Radio Television, Abbout Productions, Treehouse media, Chart, the Postoffice, and Bekaa Group.

“The big challenge was to secure the [budget to make a film of the] quality that I was dreaming of…to shoot the story I’d been dreaming of,” says Kammoun. “My obsession, and that of my producer Sabine Sidawi, and all the team, was to preserve that quality. It was extremely tough. Only limited resources were available on the ground.

“Even in Hollywood you hear these stories of ‘If only we had another $15 million’,” he laughs. “In our case there were a number of things that were complicated to do technically. My God, shooting horses at the track, staging your own races. We had a large cast and a small budget, so the challenges were huge.

“It was a life-changing experience, one it will be very difficult to manage a second time,” he. continues. ”At the same time, I’m very pleased with the film. Knowing all the challenges, the lack of resources, I’m proud of it.”

Like many filmmakers of his generation, Kammoun is a great lover of film and the theatrical experience but, when it comes to getting his work out there, the lockdown has made him a believer in the streaming services.

“It’s a difficult question because of course I want to show the film on the big screen if it’s possible, but the streaming platforms are here to stay. Streaming, and its ability to potentially reach so many people, is a big deal. Yet this film was shot using vintage anamorphic lenses to get the look we wanted. Sharing it on a big screen will be a different experience.”

-

Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Film Festival launches defining first edition

No comments yet