Eye-catching collage brings archive materials to life in director Lei Lei’s family history documentary

Dir/Scr: Lei Lei. USA/Netherlands. 2022. 104 mins.

Chinese-born, California-based writer-director-animator Lei Lei continues his imaginatively playful, warmly empathetic and illuminating interrogation of his family’s 20th-century history with Silver Bird And Rainbow Fish, tracing the experiences of his father and grandfather from the late 1960s to the early ’70s.

Silver Bird And Rainbow Fish establishes an idiosyncratic and distinctive aesthetic

This significantly longer and more ambitious follow-up to his well-received, 68-minute Breathless Animals (2019) — based on the recollections of Lei’s mother — again enlivens archival materials by manipulating and distorting domestic snaps and widely-disseminated propaganda images into kinetic, pop-art collages. The leisurely-paced results feel a tad overstretched at 104 minutes, but a launch in Rotterdam’s Tiger Competition augurs a healthy run in festivals skewing towards animation, human-rights themes and documentary work.

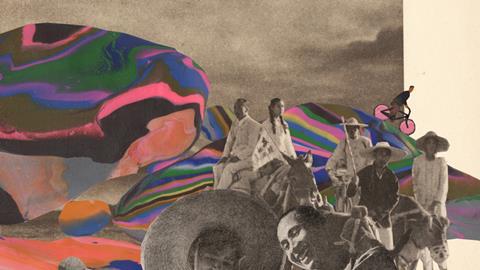

Pretty much straight out of the gate, Silver Bird And Rainbow Fish establishes an idiosyncratic and distinctive aesthetic: Lei augments old photos with brightly coloured overlays, and is insatiably fond of shocking-pink hues. The Chinese countryside of bygone days can thus, in his hands, assume the contours of Oz as seen during an LSD-trip. The faces of his family members — including his father Lei Jiaqi, grandfather Lei Ting — are meanwhile nearly always obscured by blobbily two-dimensional plasticine renderings, stylisations of a deliberately child-like simplicity.

Divided into four main chronologically-distinct chapters plus a prologue and a very brief fifth chapter which serves as coda, the film begins in the family’s native Ningdu region of Jiangxi province during the deceptively calm period prior to the start of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. A high-ranking bank-official, Lei Ting was one of countless “bourgeois” capitalist victims of the Revolution’s notorious purges; his punishment included exile to a village nestling in remote mountains. The film’s second half dramatise this change of environment by frequently dwarfing human figures in huge, forbidding natural landscapes — contrasting with earlier sections where close-ups and medium shots predominate.

Lei likewise fluently adapts his styles of animation to the changing epochs, but certain unifying methods — including those flattened, expressive plasticine faces — are retained throughout. The quirky visages feature in the most striking of the picture’s myriad symbolic flights of fancy, when Lei’s hands are seen clumping dozens of them together into a jumbled, brain-shaped lump — representing how Chairman Mao’s brand of Communism subsumed individuality into collective consciousness.

The audio also provides useful continuity across the chapters, Lei including numerous rough edges from the sound-recording process along with apparently superfluous bits of chat in which he candidly speaks. Editing in collaboration with veteran Dutch cutter Patrick Minks, whose credits stretch back more than three decades, Lei adopts the ruminative pace of older folk as they ramble down various memory lanes.

His concern is almost always with the micro — specific incidents of particular importance to the family, but which might seem trivial to outsiders — rather than the macro. The intention is evidently not to tackle Maoist oppression, radical upheaval and associated horrors directly, rather to find corollaries that can accessibly convey their disorienting social, psychological and even physical impacts over time.

Also this is not, we quickly understand, a family keen to dwell on traumas or express strong feelings. And while the visual style is often eye-poppingly extravagant in its candy-coloured, surrealism-informed excess, the prevailing emotional tone is one of surprising restraint. This is typified by Tessa Rose Jackson and Darius Timmer’s subtle, sparely-deployed score, informed by the less is more dictum which directors of so many current documentaries regrettably ignore.

Production companies: See-Ray Studio, Submarine Film, Chinese Shadows

International sales: Asian Shadows, contact@chineseshadows.com

Producers: Lei Lei, Bruno Felix, Janneke van de Kerkhof, Isabelle Glachant

Editing: Lei Lei, Patrick Minks

Cinematography: Lei Lei

Music: Tessa Rose Jackson, Darius Timmer