This year’s crop of documentaries notably includes films holding vested interests to account. Screen talks to the filmmakers who go where the mainstream fears to tread.

The concept goes all the way back to classical Greece, but lately speaking truth to power has seemed to many to be both more necessary and more risky than ever.

And while it appears to have led some mainstream news organisations to become more cautious about standing up to power, the necessity has inspired documentary filmmakers — in the US, Europe and elsewhere — to come up with some of this year’s most acclaimed features.

In Orwell: 2+2=5 — acquired by Neon for North America ahead of its Cannes premiere and set for release by Altitude in the UK next spring — Raoul Peck gives his urgent take on the modern-day relevance of the author of Animal Farm and 1984, juxtaposing readings from George Orwell’s essays and diaries with cinematic references, historical clips and globe-hopping recent news footage.

The film’s producer Alex Gibney approached Peck — who grew up amid political turbulence in Haiti and the Congo and previously made Bafta-winning James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro — with the opportunity to get full access to the Orwell estate.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” acknowledges the director. “But I still had the preconceived idea that Orwell was a science-fiction writer, and that was a negative for me because I always want to deal with reality in my films. I make films because I’m engaged in politics now.”

Peck reconnected with Orwell’s work, however, over a shared motivation to oppose societal wrongs. And his approach to the film, he says, “was not to make a biography. My approach was, how can I bring Orwell’s thoughts to a general audience? I knew I had to find the essence of Orwell.”

To give voice to the writer, Peck recruited UK actor Damian Lewis to create an in-character voiceover of excerpts from the diaries and essays. The director used clips from old films, including the 1956 and 1984 screen versions of 1984, to illustrate Orwell’s thoughts and show their relevance, and found contemporary news footage — from the US, Russia, China, the wars in Ukraine and Gaza and other global hotspots — with uncanny echoes of the author’s words.

“Orwell’s groundwork was to find the toolbox of authoritarianism,” explains the writer/director, who works out of Paris, New York and Port-au-Prince, Haiti. “What is happening right now is exactly that, it’s using that toolbox. So it wasn’t hard to find examples. In fact I had to be very selective.”

The effect of his take, Peck hopes, will be to “modernise [Orwell’s] thoughts, and also to break away from the idea that he’s a dystopian writer, that he’s writing about the future. No — he’s warning us about a potential future, except that now we are in it.”

Cover-Up revealed

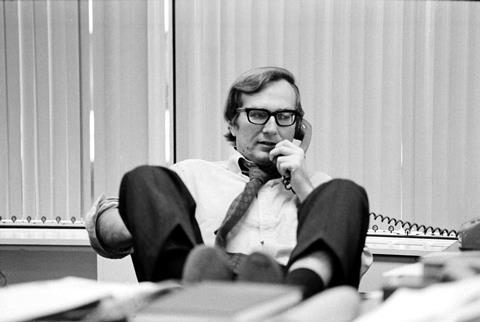

Cover-Up takes a more recent revealer of truth as its subject: Pulitzer Prize-winning US investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, known for his exposure of the Vietnam War’s My Lai massacre and his detailing of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib in Iraq, among other reporting.

Producer/director Laura Poitras, an Oscar and Bafta winner for her 2014 whistleblower documentary Citizenfour, first approached Hersh about doing a film 20 years ago. “I was fascinated by him as a potential protagonist for a film,” says the filmmaker, “because all of my films are portraits of people who are confronting power at these historical fulcrum moments — not just through an opinion, but through information and knowledge, and using their brilliance to confront power, particularly US power. Sy has changed the course of how [the US] understands itself, so he’s a natural fit for me.”

Protective of his sources, Hersh long resisted, but finally agreed to participate after seeing All The Beauty And The Bloodshed, Poitras’s most recent feature doc as a director, and also because he sensed a growing threat to his profession.

“He feels investigative journalism is in a dire situation right now,” says Poitras. “It’s not just that there aren’t investigative journalists, but what are the institutions that are willing to invest money into this kind of reporting and take the risks, which come with legal threats and the power of the government coming down on you?”

Acquired by Netflix after its Venice Film Festival premiere, Cover-Up combines contemporary interview scenes shot over multiple sessions in Hersh’s office — during which the sometimes-prickly subject makes clear his reservations about the project, even threatening at one point to quit altogether — with archival material researched by producer Olivia Streisand on events Hersh has covered over his 65-year career.

“The film is impossible without what [Streisand] found,” says Mark Obenhaus, who directs with Poitras and previously worked with Hersh on several TV projects. “She found stuff we could only imagine.”

During the interview scenes, Poitras and Obenhaus question Hersh about criticism of some of his techniques, such as the use of anonymous sources, as well as his journalistic successes.

“We had to use the same standards that he would have used,” says Poitras. “We wanted it to be both a process film about journalism, how does a story break and following Sy beat by beat, and also a critique of the media and journalists. Sy says early in the film that the problem with the press is not censorship but self-censorship, and that’s an idea that’s very relevant.”

Finding Antidote

The dangers of speaking truth to power become clear in Antidote, which centres on Bulgarian investigative journalist Christo Grozev and his use of ‘open-source’ techniques — such as social media posts and satellite imagery — to expose the murder programme operated by Vladimir Putin’s Russian regime.

UK director James Jones had been approached to make a film about what he describes as the “greatest hits” of Netherlands-based independent investigative collective Bellingcat, provider of open-source intelligence on war zones and human rights abuses, including poison cases linked to the Russian secret service.

However, six months into filming that project, “everything was just turned on its head”, says Jones, when Grozev, then Bellingcat’s lead Russia investigator, learned he had become a target for Russian assassins.

Antidote — which premiered at Tribeca in 2024 and was released in the UK in March by Dogwoof — also deals with an unnamed whistleblower who escapes Russia, as well as the case of detained Russian political activist Vladimir Kara-Murza. But it has the plight of Grozev, isolated in New York and separated from his family in Europe, at its centre.

“Making a film about Russian spies and assassins can be exciting,” says Jones of the project’s original conception, “but there’s a danger it’s quite dense and heavy. And hopefully in the end the film is quite human — it’s about what Christo and the two other main protagonists risk and sacrifice standing up to a regime like Putin’s.”

With the sudden change in Grozev’s situation, adds Jones, the film “became more universal. We were less bogged down in lifting the lid on the poison programme and the murder apparatus and it became about the bravery and sacrifice of a few individuals.”

Making such films might be dangerous in itself — Jones reports a break-in at his production office after Antidote was announced, and the film’s edit house was hacked — though for the filmmakers the cost may be worth it.

“[What] gets me excited is not necessarily trying to change the world, but trying to counteract someone who is lying about some wrong they’re committing,” says Jones, who is currently completing a film about the Fukushima nuclear accident and developing The Face Of Power, about Putin himself. “You want to make something that’s cinematic and compelling; you never want to make something that’s lecturing. But the thing that motivates me is to expose some reality that someone’s trying to cover up.”

Charting the Apocalypse

Power and democracy are seen from a personal viewpoint in Apocalypse In The Tropics, Brazilian filmmaker Petra Costa’s follow-up to her documentary The Edge Of Democracy, Oscar-nominated in 2020. Where the earlier film looked directly at Brazilian democracy in crisis, the latest investigates the increasingly powerful grip that Christian evangelical leaders hold over the country’s politics.

The investigation was sparked by an encounter Costa had while shooting Democracy with a pastor who was also a congressman. “He handed me a Bible and asked me to accept Jesus,” she explains. “That contradiction, of being evangelised in the centre of our democracy, was the genesis.”

When she began to shoot new footage for Apocalypse in 2020, Costa had impressive access to current Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and to Silas Malafaia, a televangelist who became, according to the writer/director, “a Rasputin figure” to the country’s former president Jair Bolsonaro, then campaigning for re-election but in September of this year found guilty of plotting a military coup.

The film — a Venice 2024 premiere, released by Netflix in July — combines interview material with shots of grassroots evangelicals in their homes and churches and with dramatic phone footage from the day in 2023 when Bolsonaro supporters attacked Brazil’s federal government buildings.

The challenge according to Costa, who has described all her documentaries as “essay films”, was to find the right balance of material and a tone that would allow the project to examine the evangelical movement without condemning it.

“This is a threat to democracy,” she says, “but at the same time it is a faith based on Christian principles of universal love. So it was a constant exercise. There was a lot of writing and rewriting and finding the right tone to talk about this that would not be judgmental.”

Going through that process has led Costa to “two seemingly contradictory conclusions”, she explains. “One is that religion is much more important to people’s lives in the 21st century than I had imagined, and will continue to be. [The other is] how crucial it is to ensure the separation of church and state if we want our democracies to survive.”

World cinema

Alongside the new projects from Peck, Poitras, Jones and Costa, this year’s field of award-contending documentaries includes titles dealing, in one way or another, with speaking truth to power.

Andrew Jarecki and Charlotte Kaufman’s The Alabama Solution tracks a campaign by inmates against a brutal prison system in the titular US southern state, and utilises footage filmed secretly by prisoners on smuggled mobile phones.

Kim A Snyder’s The Librarians focuses on library workers united to combat book banning in Texas and Florida. Mohammadreza Eyni and Sara Khaki’s Sundance prize-winner Cutting Through Rocks centres on the first woman elected to the local council in an Iranian village.

Russia comes under scrutiny again in David Borenstein’s Mr Nobody Against Putin; Nyle DiMarco and Davis Guggenheim’s Deaf President Now! chronicles a 1980s civil rights struggle at the world’s only deaf university; and Brittany Shyne’s Seeds, another Sundance winner, profiles Black generational farmers in the American South.

The funding outlook for future political documentaries is uncertain. While backers including Netflix, Plan B (both of which are part of Cover-Up and Apocalypse In The Tropics) and Impact Partners (involved in Antidote and Apocalypse) remain active, there are concerns that corporate caution and cutbacks in public television will soon make funding even harder to find than it is now.

“The big streamers increasingly are owned by corporations who don’t want to touch something political,” says Jones, whose Antidote was picked up by US public TV strand Frontline. “The documentary world is looking for alternative sources of funding to still be able to make these kinds of films.”

Documentary filmmakers, however, are used to financial challenges and will not be easily put off from what many see as a crucial role. “Doing these films that are confronting power over and over again is the type of work that makes me feel I have a sense of purpose,” says Poitras. And that purpose does not conflict with compelling storytelling, she insists: “I feel like I make films about people who do brave things, and there’s a lot of drama to that.”

Peck puts it simply. Being an artist, he argues, “is a privilege, and if it’s a privilege we are supposed to give back to the society that enables us. It’s my job to yell.”

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

No comments yet