As his latest film receives its world premiere at Venice, the director talks about getting movies made, film vs digital and what he thinks about a 12 Monkeys TV series.

Terry Gilliam’s first film since The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus has its world premiere at the Venice International Film Festival today [Sept 2].

The Zero Theorem stars Christoph Waltz, fresh off his Oscar-winning turn in Django Unchained, as a computer hacker trying to discover the reason for human existence. It co-stars Matt Damon, Ben Whishaw and Tilda Swinton.

Speaking shortly before the festival, the 72-year-old director talked about the speed of making the film; getting the best out of traditional film and digital technology; what drives him to keep making movies against the odds; his thoughts on a 12 Monkeys TV series; and bumping into Sting.

Is Venice a festival you’ve been to a lot?

I’ll take any excuse to go to Venice and having a film in Competition is good enough.

I’ve been at least twice. I remember going with The Fisher King [in 1991] when Mercedes Ruehl won best actress. I also went for The Brothers Grimm [in 2005], which was great fun. That year, Heath [Ledger] had three films in the festival at the same time, which is extraordinary.

Let’s just see if the city’s still above water.

When did you finish The Zero Theorem?

Last week [laughs]. We still have to do one more thing. After a year of uninterrupted work, I thought we had finished and we just discovered something on Friday night. One credit is missing so we’ve all come screeching to a halt.

How did the film first come about?

It began five years ago. [Richard] Zanuck, who sadly died last year, had been trying to get me involved in the project. His son, Dean, was producing it. I was intrigued by a lot of the ideas and the writing. The most bizarre thing was that it had been clearly written by someone who had seen all of my films.

On one level it was familiar territory, re-juggled and played with in a very different way. We danced around this for about a year and in the end I went off and did [The Imaginarium of Doctor] Parnassus.

Last year, after 12 months of trying to get a certain project going, the financial package crumbled at the end of May.

So at the beginning of June, I was looking at the rest of the year without a film or anything substantial to do. My agent said: “What about The Zero Theorem?” and approached [producer] Nicolas Chartier. He said: “Yes,” and off we went.

So in October, we were shooting. I’ve never done a film that quickly, from the idea of “let’s go” to shooting. It was quite amazing.

There is something to be said for that sort of momentum.

That’s what has been interesting about the whole project. It involved a much lower budget than I’ve had in 30 years. The shooting schedule was pretty much the same as [Monty Python and the] Holy Grail. Everything was fast. And if that wasn’t fun enough, we did it in Bucharest.

Was it the first time you’d shot there?

Yes, but Patrick Newall – who was the producer in Bucharest – had done several films there and the crew was great. There were a couple of areas where we were continually surprised at how un-great they were [laughs] but the camera crew, the electricians, the grips were as good as anyone we’d ever worked with. The painters and art department were fantastic.

I would go back there. I loved working there and the people. Bucharest was a strangely inspiring city.

It’s interesting to hear you compare the shooting schedule with Holy Grail.

Then we didn’t know better. When you’re 70-something and you know better but do it fast anyway, that’s when life gets interesting [laughs].

Did you shoot The Zero Theorem on film or digital?

That’s an important film because I have to announce to the world that we are the first ‘one size fits all, full frame, semi-vinyl motion picture’. I hope the world is ready for it.

Our future, like all futures, really looks to the past - so ours is a retro-future.

That fact that we’re shooting on film is already a retro idea. I wanted to get on film what you used to see in old, silent movies where you could see the entire full frame, including the edge of the gate so those rounded corners are there.

I thought that so many kids now buy vinyl records that should do a vinyl film.

Have you shot on digital before?

Yes. I did a short movie a couple of years ago called The Wholly Family. It’s fine but it doesn’t do certain things that film does. It still doesn’t have the range.

If you’re shooting quickly, as we were, you make mistakes – things happen that aren’t perfect. The good thing about film is that it captures information in a different way. With digital, it’s almost too precise. Because we shot on film, we were able to make some scenes look better than what happened on the day.

But I don’t want to see a film projected on film anymore. I want to see it in digital because it stays clean and the film doesn’t get scratched and covered in dust. Digital’s beautiful.

And when you’re grading a movie digitally, you have much more control over the original material. That’s why this is a semi-vinyl motion picture.

It looks like a lot of the effects were practical as opposed to CGI. Is that right?

Yes and no. There are plenty of real effects but also about 230 VFX, CGI shots. It’s a mixture.

I like to build a set big enough for the actors to be in a real world, with things to play with, but the backgrounds can be digital. I can’t stand actors having to work in a completely green screen environment, reacting to imagined, unseen creatures.

It’s become increasingly difficult to finance films and this is something of which you have a lot of experience. What still drives you?

Well, there you go. Some people grow up and get intelligent, others just stay stupid [laughs].

I think I become possessed with things and I have ideas that I want to get across. They are slightly more complex than The Lone Ranger but that’s the battle.

Even when I’m doing a low budget film like this, it’s only been possible due to the people I’ve got on board. Luckily, Christoph [Waltz] – who waits till he’s 52 years old before the world realises what a brilliant actor he is – has become bankable to a certain degree. That’s how it works.

I talked to the producers and said: “If Christoph and I want to do this, will the film be greenlit?,” and that’s what happened.

Then we got Matt Damon, Tilda Swinton, David Thewlis, Ben Whishaw and Sanjeev Bhaskar. That’s an extraordinary cast who are basically working for scale. If the film attracts anybody, a lot of it will be down to their participation. People want to see what they’re up to.

That’s hard though. Once you’ve got the film made, how do you get the public’s attention? That to me is the real conundrum when you’re competing with budgets of $100m promoting a film, which the studios are able to spend.

You say you become possessed with ideas that you want to get across. What were the ideas you wanted to get across in this film?

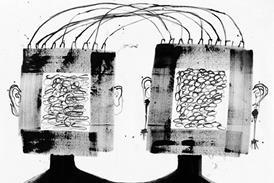

I’ve become obsessed by the connectivity of the world. We all seem to be part of this neural network and only exist by Tweeting and Facebooking. We sit at a table having dinner and have to connect with someone else to let them know we’re sitting at a table having dinner. This gets very weird.

The other aspect of the connectivity is our good friends at GCHQ (Government Communications Headquarters) and the NSA (National Security Agency).

How do you separate yourself? Can you separate yourself? Can you be alone? How do you know who you are if you’re constantly having to connect with somebody else to react to whatever you’re doing or thinking?

There’s a line in the film: “I was alone but never lonely.” That intrigues me.

It’s about a character who does try to disconnect. On one level, his job keeps him connected to work but he disconnects from humanity and people. Unfortunately – or fortunately, as the plot progresses – he is brought back in contact with his humanity. In a strange way, he loses his own humanity by disconnecting.

Sounds like a good car chase movie, huh? [laughs]

Syfy has ordered a pilot for a TV series based around 12 Monkeys. What are your thoughts on that?

I know nothing about that. That’s just ridiculous. I have no idea, even whether it’s real or even if it’s contractually possible. But it doesn’t have anything to do with me and no-one has contacted me.

It’s a very dumb idea. That’s what I think. If it was going to be any good it would have to be written by David and Janet Peoples, who wrote the film, otherwise it would just be another version of Time Bandits.

12 Monkeys is one of my favourite films. Was it tough to make?

The script was just wonderful and the cast turned out to be just brilliant - and I didn’t fuck it up too badly.

It was a studio film. Sure, it was hard to get the film going but once Bruce [Willis] and Brad [Pitt] were on board, off we went. The whole thing was done for around $29m. Bruce worked for scale, Brad worked for next to nothing and the person who doesn’t get the credit she deserves is Madeleine Stowe who is a wonderful actress.

The budget for The Zero Theorem was a little less, right?

Considerably. But it looks like a $40m movie.

So have you been possessed by what your next project will be?

No, that’s the problem. Thank god I’ve somebody to talk to today because I’m suddenly alone and lonely. It’s that moment when it’s done and you go into freefall. The thing that has been taking up your waking – and many of your sleeping – hours is finished. It’s very weird. It’s the closest thing a man can experience to childbirth, I think.

Even after all these years you’re still not used to the feeling that “it’s done”?

You get a little bit better at it but it’s a strange one. I bumped into Sting a month ago and he had just finished his new album and was like a little kid, telling everyone: “I just finished it this morning.”

Suddenly you’re vulnerable and thrown out into the world, without any structure around you. It’s quite interesting.

Well, I can’t wait to see what you’ll do next.

Me too.

![[Clockwise from top left]: 'The Voice Of Hind Rajab', 'A House Of Dynamite', 'Jay Kelly', 'After The Hunt', 'The Smashing Machine'](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/1/7/0/1459170_veniceawards_837515.jpg)

![[L-R clockwise] Estela Valdivieso Chen, Singing Chen, Jeff Tsou, Shih-Ching Tsou, Lau Kek-Huat](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/7/0/8/1463708_tcfffilmmakers_12436.jpg)

1 Readers' comment