The daily lives of complicated characters, women trying to break free from what binds them, inhabit the films of Andrea Arnold.

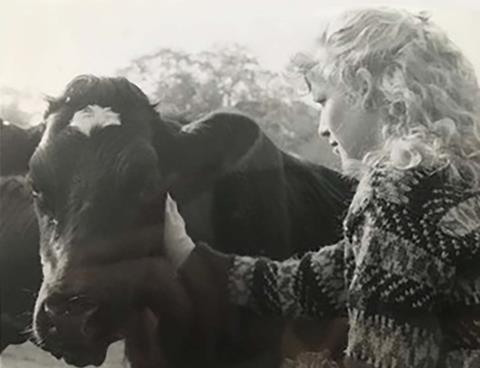

Now to Red Road’s Jackie, played by Kate Dickie, Katie Jarvis’s Mia in Fish Tank, Kaya Scodelario’s Cathy in Wuthering Heights and Sasha Lane’s Star in American Honey, Arnold has added Luma, a dairy cow who lived and died on a farm in southern England and whose quotidian existence the director filmed over four years for what became her first documentary, Cow.

“I’ve always thought if you looked at anybody’s life, like anybody, and followed them around, no matter who it was, you would find empathy for their humanity,” says Arnold. “And then I extended it and wondered if I tried doing that with an animal, whether or not you’d get to see their consciousness and see their personality.”

Arnold’s affinity for the natural world is apparent in all of her films, the camera’s gaze alive to the organic environment in which her characters live. The idea of a film centred around farm animals had hummed in her mind for years before a chance meeting on a Soho street with Jess Search, founder and chief executive of the not-for-profit Doc Society (then called BritDoc), exploded it to life.

“Jess said, ‘Have you ever thought about doing a documentary?’ And I said, ‘Well, I have got this idea,’” Arnold recalls. “I went in to talk to her about it and she gave me a little bit of development money and introduced me to Kat [Mansoor of Halcyon Pictures] who produced it.”

That was about eight years ago. The project took its time: they had to find a farm, a director of photography, backing. Arnold hadn’t even decided what animal to focus on.

In the search for a DoP, Arnold and Mansoor based themselves in a supermarket café near Mudchute Farm on the Isle of Dogs, a peninsula on the Thames that lies in the shadow of the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf in east London. They needed someone who was going to be available to work on-and-off for a long time and really connect with the animal.

“We met all these lovely cinematographers who would come over for a cup of tea in the café and then they would go off and shoot an animal on the farm,” Arnold explains. “Often people have not done a lot of filming of animals. It was a way of seeing how people connected.”

Herd mentality

Ultimately, they didn’t find their DoP that way. Not long out of the celebrated Lodz Film School in her native Poland, Magda Kowalczyk sent a test of some cows she had filmed. “My memory is that she shot their heads so she was down with the cows,” says Arnold. “It was beautiful to watch them and I really enjoyed watching them. I started thinking about what they were thinking about because of the way we were looking at them.”

It is an approach Kowalczyk would take with Luma. “The brief was to follow Luma, to keep with Luma,” says Arnold. “And Magda did. Luma goes for milking with the crush of cows and Magda’s in with them. Magda would worry me sometimes as she would get right in with the herd.”

Arnold and Mansoor took the idea to Christine Langan, then-head of BBC Film, with whom Arnold had made Fish Tank and Red Road, who agreed to back the film. (When Rose Garnett left Film4 to take over from Langan at the BBC, it was fortuitous that Arnold knew Garnett from her other two features, Wuthering Heights and American Honey, which she had made with Film4.)

It is testament to Arnold and the passion she ignites in her partners that she took such collaborators with her — because it was not clear for a long time, even to the filmmaker herself, what Cow was or what it could be. “Even Kat took a little while to understand what I might be getting at,” she says. “Even I wasn’t sure how it would land because I didn’t know whether just by following [Luma] you would get to understand and see her consciousness. I believed you could, but I wasn’t sure whether people would actually see her in the way I saw her.”

Arnold filmed Luma at Park Farm over a period of about 30 days over four years from 2016. The farm would keep in touch about specific events such as a visit by the vet, and Arnold and Kowalczyk would go together. Filming slowed down when Arnold spent months filming HBO TV series Big Little Lies in the US.

The filmmaker is clear her intention was never to anthropomorphise Luma. “We can’t get inside the cow’s head, that’s not possible. We just need to watch her and watch her reactions to what happens to her. We can make up our own minds as to what is going on.”

Cow made its debut in the new non-competitive Premiere section of Cannes Film Festival in July. The film had been ready for a year, with Arnold apparenlty not tempted to tinker with it during the Covid‑19 lockdown, devoting herself instead to writing a screenplay for a new film. Busy in Cannes with her duties as chair of the Un Certain Regard jury, it was not until the film screened at the BFI London Film Festival a few months later that Arnold says she was able to appreciate how it was being received by audiences.

“It is the most intense response I’ve ever had to a film,” she says. “Because people don’t just see a cow, they also have all sorts of other experiences.”

Arnold says making Cow and recognising that audiences do apparently see Luma the way she herself sees her, has emboldened her as a filmmaker.

“It makes me want to take risks,” she says of how Cow — which Mubi releases in the UK and Ireland in January, and IFC Films in the US — might inform her next films. “The filmmaking world is a business. There’s always a tussle to balance art and business. And I’m realistic about the business of it — I try to be, anyway. Cow was not an expensive film and I hope it will make its money back, and all the people that put money in will get their money back. But I sometimes think the business of it inhibits filmmakers from being courageous.”

She refers to a scene early in the film, during which the audience sees Luma give birth from behind, as one she would shoot differently now. “I just got braver about keeping with her head. Sometimes less is more, and the more the audience have to work, the more cinematic it is.”

Arnold reflects on how this builds on her filmmaking technique: “There’s nothing like bringing something to life that you have a passion for. My things start with images, and then I kind of start digging around the images. I just want to continue doing that.

“I’m happy that Cow is getting seen and Luma is getting seen. When we were editing, I was watching her and I felt after a while that she felt us seeing her. I really felt it. When you’re looking at an animal, or even another person, or anything living or even a plant, if you respond to it and you respond in a good way, I feel like it responds back in a good way. We are all connected to everything living. I felt Luma felt seen and that feels quite profound to me.”

No comments yet