European countries are taking on the big US streamers, seeking to regulate their activities so they invest more in local production. Screen reports on a struggle that has major implications for European film funding — and why the UK is taking a different approach

Slowly but surely, Europe is trying to tame the US streaming giants. Once market disruptors, the likes of Netflix, Prime Video and Disney+ have become market dominators in many European Union (EU) countries. By the end of 2021 these three US SVoD titans accounted for 71% of Europe’s 189 million subscriptions, according to figures from the European Commission’s European Media Industry Outlook report, published in May 2023. US films and TV series dominate on such platforms, accounting for 47% of catalogues and 59% of viewing time.

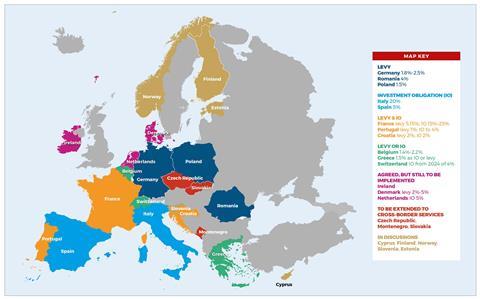

Unsurprisingly, such figures have brought the streamers firmly into the crosshairs of concerned EU governments, regulators and industry organisations. Since 2018, 17 countries in the EU have chosen to impose financial obligations on streamers so they invest more in European films, documentaries and TV dramas. These take the form of levies that are paid into national film and TV funds and/or investment obligations that mandate a certain amount of spending on European productions (see below).

The number of EU countries imposing financial obligations on streamers only looks set to rise. Another five countries are in discussions about initiating such measures.

The current financial commitments that have so far been imposed on streamers are likely to be just a start. Some countries are reviewing their existing legislation to make streamers invest yet more. They also want investment obligations to be tightened, forcing streamers to invest in certain kinds of content.

There are calls for the financial obligations to be expanded too. The groundwork is already being prepared for a new front in Europe’s wrestle with the streamers — over intellectual property rights. Many European executives want the rights to stories that are developed and created by European producers for streamers (many subsidised by national funds and tax incentives) to remain in the hands of European creatives, rather than be owned by US companies.

There is also a debate brewing about what streamers can claim as a ‘European’ production: currently, films and TV shows from the UK are still considered European, despite the territory no longer being a member of the EU. (At Cannes this year, EU commissioner Thierry Breton noted that 30% of “so-called European” works on streaming platforms in Europe are actually British or co-produced with the US.)

The streamers, of course, are not taking this lying down. There has been intense lobbying to push back against increased regulation, with a European VOD Coalition launched last year whose members include Disney, Netflix, Warner Bros Discovery, Viaplay and Sky.

Meanwhile, streamers have emphasised to press and politicians alike how much they spend on production in Europe (without necessarily providing figures) on series and features such as Netflix’s Lupin and All Quiet On The Western Front, Prime Video’s The Gryphon, Greek Salad and Culpa Mia, and Disney+’s The Good Mothers andKaiser Karl. Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings, on a visit to its Amsterdam HQ earlier this year, pointedly described the streamer as the “biggest builder of cross-European culture in the EU” for its success in getting Germans to tune into French series or Italians to watch Spanish films.

Quiet revolution

The EU’s Audiovisual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) is something of a mouthful but its blandly bureaucratic name masks a piece of legislation with far-reaching consequences for the film and TV industries.

AVMSD, and its predecessor the Television Without Frontiers Directive, has provided a framework for each EU country to regulate its audiovisual media sectors. In 2018, the growth of streaming services led to a revision of the directive. After intense negotiations, two major changes were introduced that applied to streaming services. Both were in line with the ultimate aim of AVMSD to promote cultural diversity within Europe.

Article 13(1) obliged streamers to provide a minimum share of 30% of European works in their catalogues and to ensure they were available prominently. Article 13(2) said that member states could also choose to impose financial obligations on streamers based on their revenues in the territory to support the production of European works.

These financial obligations could take two forms: direct investment into European productions (an investment obligation) or a contribution to national funds (a levy). Countries could choose to introduce one, both at the same time, or allow the streamers to choose which they preferred. Most direct investment obligations require streamers to contribute through commissions, co-productions and acquisitions. Levies, meanwhile, are usually collected by national film funds and redistributed to the local industry. The rules allow member states to target streamers even if they are not based in their country.

These revisions to AVMSD were “a big win for European production and independent production in general,” says Mathilde Fiquet, secretary general of the European Audiovisual Production Association (CEPI).

Initially, the financial obligations were slow to be imposed. Some countries were worried about deterring streamer investment by imposing regulations. The pandemic also delayed the rollout in EU member states. But in recent years the introduction has accelerated.

Alexandra Lebret, managing director of the European Producers Club (EPC), says the financial obligations on streamers have proved a boost for “European diversity, particularly the multiplicity of languages and culture in Europe”. Her EPC colleague James Hickey, the former head of Screen Ireland, says they are underpinned by a principle that “people who are taking revenues out of a particular culture owe an obligation to make a contribution back”.

Both say it is important for the financial obligations to be implemented in every EU territory, particularly smaller ones where it is harder to fund indigenous, local-language content. Lebret and Hickey stress that the rollout of financial obligations is an evolving and ongoing process. They point to Denmark and the Netherlands, which this year have each agreed to impose financial obligations on streamers for the first time. Meanwhile, the Czech Republic has raised its levy on streamers to 3.5%. Germany is looking to expand its rules, while Ireland is to introduce a levy that will be spent mostly on independent productions and will set rules governing IP ownership.

After a period of intense lobbying, Denmark recently opted for a maximum 5% levy on streamers. Conservative estimates suggest the levy will raise around $14.6m (€13.4m/dkk100m) from streamers, some of which invest very little in Danish production. The proceeds are expected to be administered by the Danish Film Institute, with 80% going to fiction and documentary films. The decision to take money from private companies and redistribute it through a national agency fits with Denmark’s political culture, which has a long tradition of high taxes and high government spending.

The Netherlands, meanwhile, is set to introduce a 5% investment obligation, which is expected to raise about $44m (€40m) for Dutch productions. This direct investment solution fits with the country’s conservative-liberal political tradition; it is a lighter touch than a levy as it allows streamers to invest in their own content.

However, the Dutch rules come with notable sub-quotas. Streamers are free to invest in any type of production except sports programmes. But at least 50% must go on films, series and documentaries; 60% must go to independent productions; and 75% of a screenplay must be in Dutch or Frisian. These sub-quotas have sparked interest in other European countries. They are viewed as a good way to increase the quality as well as the quantity of productions in which streamers invest.

For Doreen Boonekamp, former CEO of Netherlands Film Fund, the Dutch measures are a “first step to boost local production to make sure the whole ecosystem becomes more circular — so the ones at the end of the value chain invest back in the beginning of the value chain.”

She would like the financial obligations on streamers to be expanded in future years. “You need to start somewhere,” says Boonekamp, who thinks the combination of a levy and a direct investment obligation is the “cleverest way” to boost and balance the quality and quantity of European production. “For the Netherlands, and for any EU member state, it’s important we keep an eye on levelling the playing field with the countries surrounding us, especially for independent film production.”

French lead

Many European executives look to France for inspiration about what financial obligations on streamers should look like. Not only does France mandate both levy and direct investment obligations, but it also imposes detailed sub-quotas that aim to support independent production and feature films, to protect the French windowing system, to prevent the money being spent only on large-budget works and popular genres, and to limit the time streamers can hold onto exclusive rights.

The French rules came into force midway through 2021. Aurélie Champagne, deputy director of legal and European affairs at France’s CNC, notes that in the first year of implementation, streamers invested approximately $174m (€160m) in France — even though the decree only came into force in the summer.

Figures for 2022 have yet to be reported, but Champagne says CNC knows that 17 movies were funded by Disney+, Netflix and Prime Video, including Cannes opener Jeanne Du Barry, which was backed by Netflix. “France has found the right balance between incentivising actors and at the same time leaving some room for manoeuvre to decide which programmes to invest in,” says Champagne, who adds that the rules have not “deterred any streamers from coming and investing in our country. Quite the contrary, they create additional revenue for all actors, and also for the CNC.”

Asked whether more European countries are likely to follow the French model, Champagne says: “I hope we can serve as an example about what functions well and what functions less well. I know many of our European partners have been more cautious in their first implementation of the levies of investment obligations, but we are talking a lot together about what we have witnessed and what is useful.”

For Fiquet, the French model is not only interesting for the extent of its obligations on streamers, but also because it addresses IP ownership. Like many others, she stresses the financial obligations many EU countries have imposed are a good starting point. “But we need to look further at how they can be adjusted to the challenges that the European audiovisual and film production sector has in Europe.”

IP ownership is the most significant issue for CEPI, stresses Fiquet. This reflects producers’ concern across Europe that streamers are more likely to retain rights to productions than traditional broadcasters. (The European Media Industry Outlook report announced that producers “perceived an increasing tendency” for streamers “to demand full ownership of rights” and that “non-EU streamers and broadcasters would be significantly more likely to keep the IP rights compared to EU players.”)

“There are opportunities to use this [financial obligation] tool as a way to support producers in keeping their IP, for instance as a sub-condition under an investment obligation,” says Fiquet. She notes the European Commission will review the AVMSD by December 2026. “We think there will be a need to reopen the AVMSD then and make sure we can continue to build on the measures that were adopted back in 2018.”

The streamer viewpoint

There has been pushback by the US streamers against the financial obligations imposed across the EU. They argue that a fragmented and complex set of financial obligations are now in place across Europe. Backing up this belief, Italy’s regulator AGCOM recently called for “simpler and more flexible” rules — stating the current regulatory system is “layered, complex, rigid and not always coherent”. As a result, that makes it difficult for streamers to ensure compliance.

Some think the many different rules in each country are detrimental to the EU’s ambition to strengthen the European single market. Furthermore, the rules could lead to streamers investing more of their content budgets in countries with financial obligations, putting those without at a disadvantage.

Some streamers privately point out the regulations are designed to promote European production, but have encouraged protectionism and a race to see who can mandate the most national production. They also say high investment obligations have led to unintended consequences — notably increased costs of production, which makes it expensive for traditional broadcasters to make local shows.

Streamers also assert that financial obligations should, according to AVMSD, be proportionate and non-discriminatory — but that is not always the case. In Italy, for example, streamers face higher investment obligations than public service and commercial linear broadcasters.

In a statement, the European VOD Coalition told Screen International: “Members of the European VOD Coalition invest in European content because consumers want high-quality and diverse entertainment choices. Disproportionate and highly complex financial obligations across Europe risk shifting the focus away from producing the high-quality content that consumers love, and could lead to less diversity and innovation. They can further become a barrier to entry for companies that want to offer their services in several countries.”

It is clear this battle will likely be fought for many years. Conventional wisdom has it that the US leads on innovation, and Europe on regulation. However, US streamers are battling on the EU’s turf. Will a regulatory squeeze finally cramp the operating freedom of global streaming platforms in one of their most important markets?

Continental divide: Streamers are now faced with a patchwork of financial obligations across Europe

Click top left to expand

So far 17 European countries have set financial obligations on the streamers. Dictates exist in Germany, Romania, Poland, Italy, France, Portugal, Croatia, Belgium, Switzerland, Greece and Spain; they have been agreed — but are yet to be implemented — in Ireland, Denmark and the Netherlands. They apply to domestic players in the Czech Republic, Montenegro and Slovakia, and are to be extended to cross-border services. Discussions about financial obligations are also taking place in Cyprus, Finland, Norway, Slovenia and Estonia.

France places the most onerous obligations on streamers, building on its long tradition of championing ‘l’exception culturelle’. Here the streamers must contribute a minimum of 5.15% of their net revenues as a levy to cinema agency the CNC, which it adds to its own funds that are redistributed to productions. The streamers must also invest a minimum of 20% of their net French revenue directly in European works (85% of which must be in works of “French expression”). In total, more than 25% of a streamer’s net revenues from France must be spent on European content.

Italy also places significant obligations on streamers — they must invest 20% of net revenues directly in European works from 2024 (50% of which must go on productions of “Italian expression”).

Poland has a 1.5% levy, while Germany has a 1.8%-2.5% levy and Romania is set at 4%. Spain, meanwhile, allows companies to choose between a 5% levy or investment obligation. So too does Greece (1.5%). Croatia and Portugal — like France — have introduced both a levy and a direct investment obligation.

Complicating matters further, some countries — like Croatia, Greece and Portugal — have set rules stating the total investment must go on national works. Others — like France, Spain and Italy — say a proportion must be spent on national works with the rest on European titles. In some countries, rules specify what kind of content must be supported. In Spain, 70% of direct investment must be dedicated to works by independent producers; in France, three-quarters must be spent on independent film production.

Sources: European Audiovisual Observatory; Studies on Media, Innovation and Technology (SMIT) at Vrije Universiteit Brussel; Screen research

Why doesn’t the UK target streamers?

The UK has taken a different approach to its EU neighbours. There are no levies or investment obligations imposed on streamers in the UK — and no producer groups are lobbying for them to be imposed. This is partly because many streamers are spending large sums on production in the UK, financing series such as The Lord Of The Rings: The Rings Of Power (Prime Video) and features including Ridley Scott’s Napoleon (Apple).

By tradition, the UK adopts a less-interventionist approach to film policy than most of Europe. The UK has not had a compulsory statutory tariff since the Eady levy — a tax on box-office receipts to fund British production — was abolished in 1985. Instead, the UK has relied on tax reliefs to provide support.

This has led to a boom in inward investment productions, many through streamers. However, independent films have found it difficult to secure funding. Last year, An Economic Review of UK Independent Film — an independent report produced for the BFI on the challenges that face UK independent films — recommended an increase in the financial contribution from large streaming services to UK independent films. This could be “either through a voluntary commitment or a requirement for large streaming services to make a modest contribution to a pot of funding that they can reclaim for creatively driven UK filmmaking (subject to a budget cap)”. However, this recommendation does not represent BFI policy.

Any official proposal would likely fall on deaf ears while the UK’s Conservative Party — with its anti-regulation position — is in power. But a general election has to be held before January 24, 2025, and the opposition Labour Party is far ahead in the polls. Could Labour be supportive of EU-like financial obligations on streamers? The shadow of Brexit still hangs over the party, which does not want to be perceived to be mimicking EU policies.

That said, countries beyond the EU are introducing financial obligations on streamers. Australia is set to impose them by mid-2024, while Canada’s Bill C-11 (aka, the Online Streaming Act) has paved the way for the government to force streamers to invest in local content.

With concerns growing about the challenges facing UK independent filmmaking, could a Labour government one day think about imposing financial obligations on streamers?

No comments yet