Pollard’s incisive work follows ’MLK/FBI’ and ’Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me’

Sam Pollard. UK. 2026. 101mins

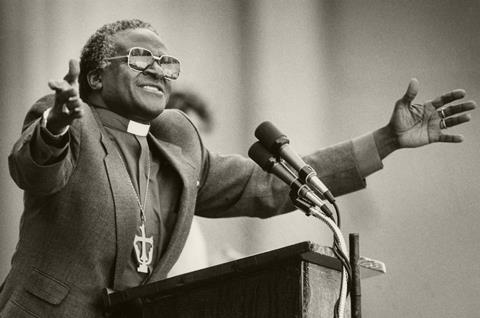

Despite its mononymous title, Sam Pollard’s latest documentary is not interested in the life of a single man, rather about how the South African leader’s political philosophy inspired generations. An anti-apartheid clergyman, the Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu argued from his pulpit for non-violent tools against a brutally racist government. That desire not only earned him a Nobel Peace Prize, it also made him a source of ire for white bigots and agitated black revolutionaries. Pollard thoughtfully interrogates the narrow middle ground Tutu perilously occupied for an admirable, galvanizing, and incisive portrait of a peaceful ethos.

Takes the shape of Tutu’s kinetic activist energy

Tutu, which premieres as a Berlin Special Screening, could be said to follow a common trend in Pollard’s career of films about Black Civil Rights activists (MLK/FBI) and boundary breaking Black pop culture figures (Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me) whose unique talents offered forms of resistance to Black folks during the 1960s. Tutu, however, does differ from those films, moving the director away from America to the African continent where he can apply his established approach of recording and defining the injustices of an era for brand new audiences. By chronicling one archbishop’s disciplined resistance against a totalitarian foe, the film is the kind of urgent call for undaunted action that offers wide appeal.

Consequently, Tutu doesn’t take a conservative approach. This is not a cradle to grave documentary that unnecessarily spends time sharing easily available biographical details —the clergyman’s birthdate, upbringing, and formative training aren’t shared. Pollard instead leaps from footage captured by journalists Roger Friendman and Benny Gool during the last 20 years of Tutu’s life to archival images spanning the 1970s to the early 1990s. While that lack of conventional grounding may frustrate less inquisitive viewers, it actually allows the film to take the shape of Tutu’s kinetic activist energy.

By not using the Archbishop’s own life as a throughline, Pollard allows himself the freedom to ask distinct questions of his subject. How does one remain non-violent when confronting intense hate? How does one retain hope without seeing discernible signs of progress? Pollard answers these questions via a cadre of talking heads, like activist Joyce Seroke; the Archbishop’s former aide Dan Vaughan; Professor Peter Storey’ and many others who knew the political figure best. They give the picture of a man guided by prayer and “the redemptive power of forgiveness.” Pollard tests Tutu’s approach by showing harrowing images whose gruesomeness shows the scale of apartheid atrocities, to question whether such offenses can be defeated through orderly means.

During the film’s superfluous three-chapter structure – it’s nonsensical to have segment titles when the film is only passably chronological – Pollard loosely winds viewers from the Archbishop’s eye-opening residence in London during the early 1970s to the height of his political prowess during the 1980s. It also includes his contentious chairing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was instituted in 1995 following the fall of apartheid and whose aim of absolution through confession is openly critiqued by some of Tutu’s closest associates.

During these segments, Tutu makes it clear, through archival interviews, that advocating for peace doesn’t make him a pacifist. In one revealing soundbite, he damns Ronald Reagan to hell for the fact that the then-American President and British Prime MinisterMargareth Thatcher had not instituted economic sanctions against South Africa. In another instance, during the country’s 1986 State of Emergency, he stands up to a mob of Black people on the verge of burning an accused informant alive.

Pollard contrasts these instances of Tutu’s fiery defiance with Friendman and Gool’s footage of the Archbishop’s frivolity. Scenes of Tutu at home with his wife Leah, who is given ample space to tell her own story through arrchive interviews, illuminate the seemingly bottomless well of happiness and laughter that allowed the political figure to carry on, despite receiving death threats. These newer images also tip a cap to Tutu’s later efforts to eradicate HIV/AIDS, and to his hope of finding peace between Palestine and Israel. By combining the civil rights activist’s past with his future, Pollard doesn’t elevate a man into a symbol. He locates the elements that made the man who helped end Apartheid.

Production company: Hidden Light Productions, Universal Pictures Content Group

International sales: Cinetic Media, sales@cineticmedia.com

Producers: Johnny Webb, Ellie Phillips, Beya Kabelu

Cinematography: Geoffrey Sentamu

Editing: Paul Trewartha

Music: Philip Miller