In celebration of the National Film and Television School’s 50th anniversary, four former students who have all gone on to flourishing directing careers share their memories of teachers, mentors and lessons never forgotten.

Since opening its doors in 1971, more than 3,800 students have passed through the National Film and Television School’s (NFTS) hallowed corridors and into its classrooms, screening rooms and edit suites. To mark its anniversary, Screen and the NFTS brought together four graduates who have gone on to have successful directing careers in film and television: Aisling Walsh (a student from 1980‑83), Sarah Gavron (1997‑2000), Michael Pearce (2006‑08) and Mahalia Belo (2010‑12).

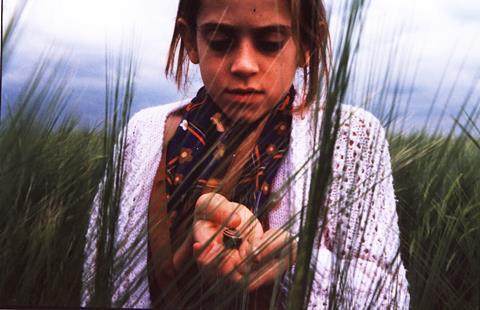

Dublin-born Walsh directed her first feature Joyriders in 1988, and her further feature credits include, most recently, Maudie (2016). She has also worked on TV series such as the BBC’s Fingersmith (2005) and TV movies including Elizabeth Is Missing (2019) and An Inspector Calls (2015).

Gavron directed TV movie This Little Life in 2003, as well as features Brick Lane (2007), Suffragette (2015) and, most recently, Rocks, which earned seven Bafta nominations this year including best director.

Pearce won the Bafta in 2019 for outstanding debut by a British writer, director or producer with his first feature Beast. His second, Encounter starring Riz Ahmed and Octavia Spencer, receives its world premiere at this year’s Toronto International Film Festival.

Belo, who directed a pair of miniseries — Requiem for the BBC and Netflix, and Heyday Television’s The Long Song for BBC, both in 2018 — is set to make her feature debut with an adaptation of Jane Austen’s Persuasion for Monumental Pictures’ Alison Owen and Debra Hayward, backed by BBC Film and Searchlight Pictures.

The quartet came together in mid-August on Zoom and this is an edited version of that conversation.

What did it mean to you to be at the National Film and Television School?

Aisling Walsh I was 22. My year were quite young. But because I came from Dublin, it was quite an extraordinary thing. I had been to art school and made little films, and I read about the film school in a magazine and wrote to them. I said, “I’d like to come over and see it,” which I did, on the boat and train, and I couldn’t believe I got in. It’s interesting to be in a place in its first decade. And it was the National Film School, we were all going to leave and make films. Everybody there was a filmmaker and we all mucked in and helped each other make our films.

Sarah Gavron I had been to Edinburgh College of Art and did an MA in filmmaking. That was the first time I made shorts and fell in love with fiction filmmaking. And everybody there was talking about the National Film and Television School, this place that was impossible to go to but was this Mecca of filmmaking. It planted the seed in my head. I went back to London and spent the next four years in documentaries. But all the time I was having fantasies about making fiction films.

I turned 27 and I thought maybe I should bite the bullet and try for the film school. But I didn’t dare try for fiction — so I was going to apply for documentary. Then two nights before the application had to be in, I stayed up and wrote a fiction application. They had this two-week course with 20 of us and were going to select five. So it was this scary induction process. I went there for three years and I didn’t regret it. It was more structured than when Aisling was there, but relatively unstructured compared to now, I think. Nobody lived there, it was the old Portakabins, and we edited on Steenbecks for the first year, then moved to digital. They had a proper sound studio, but there was a kind of flea-ridden old cinema. Maybe it wasn’t flea-ridden, but it felt flea-ridden. But brilliant teaching.

Michael Pearce I was 25 when I went and I was the youngest in the directing group. I had this expectation you had to have worked in the industry before going there. But I applied anyway because I had my sights set on the NFTS since I was 18. Even doing my degree at Bournemouth in film directing, I saw it as a stepping stone to get to the NFTS. I applied and I got an interview, and I remember walking into the interview room, which was with [then co-heads of fiction] Lynda Myles and Ian Sellar.

Often they get a previous student to do some of the interviews as well. And it was Lynne Ramsay. I was a fan of her shorts and Ratcatcher. So I was walking into an interview and meeting one of my filmmaking heroes, and I remember trying to ingratiate myself to her because I’d read she was about to do The Lovely Bones. I asked her about it and she said it was falling apart. And I thought, I’ve just fucked it. I remember coming out, seeing all the students talking about films and moving equipment about, and I wanted to be there so bad. I was like, if I don’t get in this year, I’m going to make more shorts and apply next year. And if I don’t get in, I’ll just keep applying until I do.

Mahalia Belo I also studied fine art, but knew I wanted to go to film school and I kept researching it every year, thinking, next year I’ll apply, I’ll be good enough next year. I kept doing that and only applied because I’d started to make fashion films to make some money, and I’d spoken to a friend of mine about the film school who said, “I’m applying.” I realised I couldn’t hold it off. She applied for production design, I applied for directing, and we both got in. I also had Ian Sellar and Lynda Myles [for my interview] and I got so nervous. I had to take deep breaths and I did a yoga move, and Lynda was like, “It’s fine.”

Walsh It’s interesting to hear everybody talking about the school, the flea-ridden cinema — that cinema was beautiful. I was there in the first decade, the school was nine years old, and every Monday we watched films. You would arrive and watch two to three films and then discuss them. In that first year, we were divided into groups and made a small fiction film, of which we each directed a scene. Then we made a documentary together, and everybody had the chance to do everything. And the school was small — 25 people in a year — so you knew everybody.

I learned how to write and was encouraged particularly by [NFTS director] Colin Young and [filmmaker] Bill Douglas. Bill came towards the middle of my second year, and we still saw each other after I left. I learned a lot from him. And some amazing directors came to the school: Bernardo Bertolucci, Alan Parker. They would come for a few days at a time and show their films and you would spend time with them. There were always ex-students teaching at the school. Jim O’Brien [Scottish-born stage and TV director whose credits included co-directing Granada Television’s 1984 adaptation of The Jewel In The Crown] taught me a lot in my first year, and we stayed in touch and later worked together on things.

Gavron We had five directors in my year. Three out of the five were women, which was unusual. We also had Jim O’Brien as a teacher, who was great, and Stephen Frears, who taught me a huge amount, mainly in the editing room. He wouldn’t say very much, but what he said never left you. I still feel I’ve got his voice in my head on a film set: “Why are you doing this? Why are you putting the camera there?”

I remember this Latvian woman made a short and he was mentoring her during that, and she said she didn’t see him all day. Then, at the end of the day, he came in and analysed everything she had done — he had been sitting on a toilet with a carefully placed mirror so he could see everything she was shooting through the bathroom door. I also stayed in touch with quite a few of the teachers. Ian Sellar was a lovely, nurturing presence but also razor-sharp. I’ve got him to come and see films since, as I have Stephen Frears. You do feel like you developed this family of mentors and peers who you can draw upon.

Pearce The main tutor we had was Ian Sellar. We were six directors at the time and Ian is someone I’m still in touch with. I sent him a cut of my recent film because he always has so much wisdom to confer. We’d sit in class and each director would pitch their idea for the short they were going to make. Ian had an uncanny ability to tease out a compelling idea for what might have been an image someone had, and found the heart of everyone’s story.

When you finished a short, you would show it in the cinema with the people from your year and the tutors, and they would tell you what they thought of it in candid terms. I remember one short I made, I had let a bad performance go on screen and I vowed to myself that day that I’m never going to put a bad performance on screen again. There were lessons you learned in that dark room that I carry with me now.

Belo There were eight [directors] in our year. I remember the dread of those critiques, but how useful it was. It wasn’t just the films we would watch; we would also watch the rushes and that was the most exposing thing ever. It made you realise you had to get very good at your craft, especially because you’re the director and the other departments depend on you at the school to make their best possible work. We felt a lot of pressure as a result. But we loved it. It built confidence. I came away from the film school with a lot of creative collaborators and deep friendships, but also confidence — and that was priceless.

Screen You mentioned close collaborators. Who did you meet at NFTS that you’ve gone on to work with?

Belo I’ve worked with [cinematographer] Chloë Thomson on everything since leaving film school. She did my grad film. We were the only women in our department. I was the only female director, she was the only female cinematographer, and we ended up working together. And production designer Laura Ellis Cricks. She was the reason I ended up going to film school, and I still work with her.

Gavron I work with Maya Maffioli, who Michael has also worked with, as an editor, and with the fact she had been at the film school there’s some connection, even though she was there way after me. A DoP I married, David Katznelson, I met there. And Jonny Persey was a producer who I worked with on a documentary [Village At The End Of The World, 2012].

Pearce I still work with Ben Kracun, who was a DoP I knew from film school. He shot my recent feature and my past one. Maya Maffioli, who edited with Sarah on Rocks, was also in my year. Laura, who Mahalia was talking about, was the production designer on Beast. So you really do meet a tribe of filmmakers, which is great.

The thing I miss most about it, in terms of finding your tribe, is that when I speak to other directors now, so much of our conversation is about the industry and about the politics of the industry, and navigating actors’ agents and financing and studios and the health of the industry. When I was talking to other filmmakers at the school, it was all about the craft. You were talking about movies you loved or you hated, and why, and what that director did with the camera or how they elicited that performance. That was 99% of your conversation. Now, for me, it’s like 40%.

Walsh It’s interesting what Sarah said about Stephen Frears. I remember Bill [Douglas] saying to me: “When you go out there, remember the picture you saw when you first wrote the scene. That’s where you put the camera.” To this day, I remember that. I went from very early on thinking I wouldn’t survive the first year to loving the place. It was my film education. I learned how to make films. I learned how to write, I learned how to direct, and I wouldn’t have learnt in the way I did, had I not gone to the school.

There was a point in my second year where I ran out of money. I had to go away and work for a bit and the school said, “We’ve got an ex-student who is making a film and who needs crew.” Myself and another student in my year were sent off. He did sound, and I was an assistant director for Terence Davies on the last part of The Terence Davies Trilogy (1983). I see Terence every now and again, and I learned so much on that film by watching somebody else.

Gavron At school I was always trying to do the right thing and fit in, and I learned that to be a filmmaker of any kind, you have to strip that away and be true to yourself and be honest with yourself and follow your instincts. Learn who you are and what your taste is and what your vision is. And like Aisling, I learned the craft. The peer group and the teachers were, in some ways, the most valuable thing about it, getting to meet and know those people. There was something about the people you sat with in your editing room, or on your film set, that was so rewarding and valuable and useful.

Belo One of the biggest things I have with my work is thinking about the opening. Ian [Sellar]would teach us, look at the opening, why you have each shot, the sound of it, even the titles. If you can imagine the opening, the rest of the film hopefully follows suit.

Pearce You just had to come in every day with curiosity and a love for movies. The goal was tune in and listen to your own creative intuition, and that was the thing you had to protect. Any time you tried to do something to be impressive or do something that was your calling card to the industry, the best work never came from that. I try and hold on to that now, to that intuition, because sometimes it’s a quiet voice, and it can be swamped by a lot of expectations and demands and pressures for a movie to perform or do well, and I just go back to those first few days of the film school. So that, and meeting a peer group that inspires you. You learn as much from the people you’re studying with as you do from the tutors, who were great.

![[Clockwise from top left]: 'The Voice Of Hind Rajab', 'A House Of Dynamite', 'Jay Kelly', 'After The Hunt', 'The Smashing Machine'](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/1/7/0/1459170_veniceawards_837515.jpg)

No comments yet