Anime is no longer just big in Japan, it’s now a truly global sensation. Screen speaks to the filmmakers behind the latest anime releases – and others influenced by the animation style – vying for awards contention

Since its inception at the 2002 Academy Awards, the best animated feature Oscar has almost exclusively gone to Hollywood movies. But in recent years, attention has turned to Japan, whose vast animation industry hit a record $25bn in 2024 across movies, streamer licensing, concerts, and more – with more than half of that coming from outside the country.

In 2025, multiple anime films have been major box-office hits both at home and abroad, with Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc and Jujutsu Kaisen: Execution cracking the box office top 10 in the US and UK, and Demon Slayer: Kimetsu No Yaiba Infinity Castle now the second-highest-grossing film of all time in Japan.

The origins of anime’s popularity in the west date back to the 1990s, when TV series such as Sailor Moon, Dragon Ball Z and Pokémon began to appear. Its recent propulsion into the mainstream is thanks to a combination of wider availability on streaming platforms such as Netflix and Crunchyroll, an embrace of alternative forms of entertainment during the pandemic, and a parallel explosion in the popularity of manga, the Japanese comics that provide much of the source material for anime.

Anime is huge, but can this year’s impressive box-office returns translate into awards, and if so, which films are poised to claim the prize?

The contenders

In terms of box-office heft, the winner is Demon Slayer: Kimetsu No Yaiba Infinity Castle. It has set multiple box-office records, including the highest opening-day gross in Japan and biggest anime opening in the US, where it was distributed by Sony-owned Crunchyroll. It is currently the year’s sixth-highest-grossing film worldwide, with $774m at press time.

Demon Slayer, from studio Ufotable, is an adaptation of Koyoharu Gotouge’s manga, which tells of a group of demon hunters in early 20th-century Japan. The anime version began on TV before leaping to the big screen in 2020 with Mugen Train. It became Japan’s highest-grossing film of all time, surpassing Spirited Away, the record holder for nearly 20 years.

“I think the success of Mugen Train and Infinity Castle comes down to the appeal of [Gotouge’s] original manga,” says Infinity Castle director Haruo Sotozaki, “but also because our anime manages to convey the charm of the original, like the phrasing of the dialogue, and the appeal of the characters, to the greatest extent possible.”

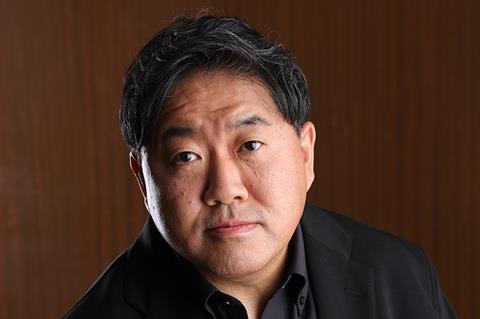

“First and foremost, we’re concerned with how to best tell the story, not box-office results,” says Ufotable president and chief director Hikaru Kondo. “But since Mugen Train was a huge hit, especially in Japan, expectations for Infinity Castle from audiences and cinemas were immense, so we’re pleased with the reaction.”

Monetary success notwithstanding, Demon Slayer faces potential hurdles with awards voters. “It’s the first part of a trilogy. It’s 155 minutes long. I don’t think most people in the Academy have been watching the series all along, and if you don’t, you’re going to be kind of lost,” says animation historian Charles Solomon.

That is also the case for Crunchyroll’s Chainsaw Man – The Movie: Reze Arc, another major success in Japan, which topped the US box office when it opened in late October. It is a direct continuation of an anime series that aired in 2022, making it largely inaccessible to new viewers.

The anime film with the best chance of awards success, according to betting markets, is Scarlet, the latest from director Mamoru Hosoda, whose Mirai was nominated for an Oscar in 2019 – the only anime film not animated at Studio Ghibli to achieve the feat. Distributed by Sony Pictures Classics in the US in February (following a brief awards-qualifying run) and by Sony Pictures Releasing International elsewhere, Scarlet is an animated take on Hamlet as a princess seeks revenge for the death of her father.

“Hosoda has been at the forefront of pushing animation in new directions, and Scarlet is his most ambitious film yet,” says Solomon, who has authored a book on the director.

Scarlet premiered at Venice, where it reportedly earned a protracted ovation. However, it opened softly in Japan in late November, placing third with $1.7m (¥270m) – far behind the $5.7m (¥890m) opening for Hosoda’s Belle in 2021 – and had taken $3.5m (¥550m) by year’s end.

Global reach

Whether or not Japanese features gain momentum this awards season, the country’s influence will loom large. Several contenders from around the world feel distinctly Japanese in terms of style and content.

Arco’s French director Ugo Bienvenu has cited anime such as Dragon Ball Z and Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke as inspirations. Netflix smash KPop Demon Hunters features “a touch of anime”, according to its co-director Chris Appelhans. Another Netflix original, the South Korean film Lost In Starlight, features more than a touch of anime, with director Han ji-won citing Makoto Shinkai and Miyazaki as influences.

Japan and its animation were also an influence on French-language feature Little Amélie Or The Character Of Rain. The film, directed by Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han and distributed in the US by Gkids, centres on the precocious three-year-old daughter of a Belgian family living in Japan in the 1960s and is based on an autobiographical novel by Amélie Nothomb.

“Most of the people on our team grew up with and love Japanese animation,” says Han, who cites Isao Takahata’s Grave Of The Fireflies and other Ghibli films as inspirations. To recreate the world of 1960s Kobe, the Little Amélie team, including art director Eddine Noël, took a deep dive into primary sources from the period, including a photo book from a Japanese family discovered at a flea market.

“We have seen all the clichés here in France, and it was important to us to be respectful about Japanese culture, especially at that time, after the Second World War,” says Han.

Vallade cites Sunao Katabuchi, the director of Second World War-set anime In This Corner Of The World, as well as The Mourning Children, an upcoming feature set in 10th-century Kyoto, as a further influence on Amélie.

“Katabuchi is a precise researcher,” says Vallade. “He spends time to find out exactly how the light would shine through a certain boat in port at a certain moment.”

The Japanese influence on the world of animation goes beyond surface-level aesthetics, says Solomon.

“You have artists like Miyazaki that storyboard the film themselves, so they have an auteurist touch to them that a lot of big American films don’t have. There’s a unity of vision that attracts a lot of filmmakers who want to be able to make this kind of statement in their work.”

Miyazaki’s portrayal of the inner lives of children, in particular, shaped how the Amélie team developed its protagonist. “Japanese animation like [Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro] takes kids seriously, knowing that kids understand more than we think they do,” says Han. “They don’t take kids as idiots, and that’s something that influenced us a lot.”

Such influence is not a one-way street. Director Hosoda cites French studio Fortiche (Netflix series Arcane) and Spain-born animator Alberto Mielgo, who won an Oscar in 2022 for short The Windshield Wiper and helped devise the visual language of Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse, as inspirations for Scarlet’s hybrid hand-drawn/3D animation style.

“Animation is currently in a period of innovation, and while anime is known for its hand-drawn tradition, when it comes to moving forward and evolving, it should embrace these new innovations while leveraging its traditions,” says Hosoda.

Paths to nomination

The fact remains that while Japanese animation has earned seven Oscar nominations and two wins since 2002, all but one of these were for Studio Ghibli films – the exception being Mirai in 2019. Ghibli, which was founded by Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki in 1985 and purchased by Nippon TV in 2023, had a strong advocate in John Lasseter at Disney, who was instrumental in bringing the studio’s films to the US.

Meanwhile, other anime films that may have otherwise garnered nominations, like Makoto Shinkai’s 2016 box-office hit Your Name, were distributed in the US by companies such as the Texas-based Funimation, which had fewer connections to the Academy and less awards-race experience.

A decade later, the distribution situation has changed, with Japan taking direct control of its properties rather than simply licensing them. Distributors Funimation and Crunchyroll were acquired by Sony in 2017 and 2021, respectively, while Gkids, which steered Miyazaki’s 2023 title The Boy And The Heron to Oscar success, was acquired by Japan’s largest distributor Toho in 2024.

Also different is the make-up of Ampas itself, following membership rule changes in the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy in 2016. “The fact people like me have become Academy members is a sign the Oscars now reflect a broader world of values and diverse perspectives,” says Hosoda, who was invited into the Academy in 2018, with Hosoda’s longtime producer Yuichiro Saito following in 2019.

“Fundamentally, it’s an American award, so it’s only natural that American studios have an advantage,” he adds. “But there are incredibly innovative movements happening within animation worldwide, and global animation itself being seen by so many people now thanks to streaming.”

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

No comments yet