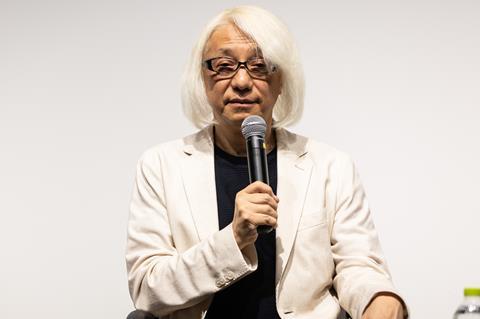

Macoto Tezka, the self-styled visualist from Japan whose father was “godfather of manga” Osamu Tezuka, is eager to make a monster feature.

Delivering a masterclass at the Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival (Bifan) in South Korea, the filmmaker spoke about the influence of his late father – known for seminal manga such as Astro Boy – as well as his ambition to make a “monster or vampire film”.

Tezka took the stage following a screening of his experimental shorts from the 1980s and ‘90s in Bucheon City Hall’s Fantastic Cube theatre. He will next act as a supervisor on Netflix animated series Pluto, a long-awaited anime adaptation based on Tezuka’s characters.

The following excerpts have been translated from Japanese and edited for clarity.

On South Korean cinema

I don’t watch that many Korean movies, so I can’t speak as an expert. In the 1990s, we didn’t get that many Korean films in Japan, but the ones we did get were very original. These days, Korean films are considered top entertainment in Japan, and Korean dramas are especially popular. Japanese filmmakers are surprised by the high quality of Korean television. I think that’s a great thing, but I feel like original films like those from the 1990s have gone down in number. In the world of cinema, we have art and entertainment, and I think when high quality films in both categories are produced, it ties in to a country’s cinema culture. In Korea, the entertainment side is already high quality, so if it raises the art level, too, it’ll be great for its cinema culture.

On the influence of his father

On a fundamental level, there’s likely no one in Japan who hasn’t been influenced by Osamu Tezuka. His influence is huge, but I think influence is something felt by a third party. In my case, he’s my father, so he’s not a distant third party. We’re strongly connected by blood. Sometimes I’m conscious of that, and other times I try to intentionally do something very un-Tezuka-like.

I’m self-taught. I learned filmmaking by myself. But when I was growing up, my father’s anime studio was right next door, so I learned a lot from the staff when I was a kid. I also realised that I wanted to do something different from what they were doing. If I’d decided to go into commercial animation, I could have, but I wanted to make experimental animation, like the short Model you saw today.

Of course, I’m Tezuka’s son and I work at the company he founded, so doing Tezuka-related work is part of my job. My [2019] film Tezuka’s Barbara is based on his manga, but it’s a project I wanted to take on myself. I wanted to keep Osamu-style elements while adding in my own viewpoint.

On wider influences

I had wanted to make films since I was in elementary school. At that time there were a lot of monster movies in Japan, which I loved more than animation. That’s probably why I didn’t go into anime.

Around that time, I also saw Dracula starring Christopher Lee on television. From then on, I loved horror films and saw all the horror films I could, including old German ones like Nosferatu and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. They’re horror, but they’re also art. So from a young age, I was into monsters, horror and art, which all feel like they’re in the same category for me: they all give you a feeling you can’t get in everyday life. I’ve made many art films, but I haven’t made a monster film or vampire film yet. Those are the two I want to make before I die.

On calling himself a visualist

My main interest is in making films, but there are so many rules in filmmaking. When I was starting out, I got a lot of advice from older directors, but some of that advice was kind of stifling. “Scripts are vital, so write a script before shooting,” or “relationships with actors are so important, so choose carefully and build up those relationships.” I realise these rules are important, but when I saw their films, I realised I wanted to do something a bit different. So I chose the title visualist, which I thought would give me more freedom.

Others in Japan don’t use that title, which means when some kind of new media pops up, I end up being offered that work. The reason I was able to direct a making-of documentary about Akira Kurosawa (in 1991) was that while other film directors weren’t allowed on Kurosawa’s set, a visualist was okay.

A message for young people

Find your own freedom. Thinking and creating freely is the most important thing in life. Society has a lot of rules, but the world of art should not. Commercial filmmaking has many rules, of course, and it’s important to study and know them, but it’s also important to get away from them and find your own way of thinking. The worst thing you can do is to tie yourself down, to assume you can’t do something. When people tell you you’re wrong, listen carefully, but don’t give up; think of how you can get them to accept your viewpoint. Remember that you are free.

No comments yet