“Tanzania is little known within the global screen sector but I’d like to believe we still pack a punch,” says Amil Shivji, a filmmaker and producer with his Dar es Salaam-based Kijiweni Productions, who is partly responsible for boosting the country’s international reputation.

Shivji broke onto the international scene in 2013 with the short film Shoeshine about a young boy whose job cleaning shoes allows him to observe life on the streets of Dar es Salaam. The film, which Shivji wrote and directed, screened at the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) and was nominated for the Young African Filmmaker’s Award (YAFMA) at the 21st Afrika Film Festival in Belgium.

Now Shivji is at the 8th Atlas Workshops, the annual industry incubator offshoot of the Marrakech International Film Festival, with his second feature film, Last Cow, which is in development.

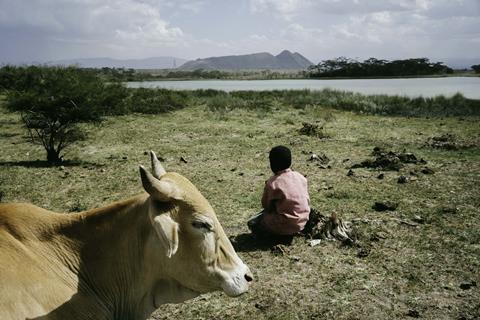

Last Cow is set within the Maasai semi-nomadic ethnic group living in Kenya and northern Tanzania. Leiyan is the young son of the chief of a village threatened with eviction so its land can be sold to a sheikh from Dubai. He is assigned to protect Naserian, the last remaining cow in the village, and events conspire to turn the cow into an almost mythical figure.

Shivji plans to shoot the project in Morogoro in eastern Tanzania in the winter of 2027, with an expected delivery in the autumn of 2028.

The total budget is expected to be €1m; Shivji and his producing partner, Tamara Mariam Dawit of Canada’s Gobez Media, have secured around €76,000 and they are seeking co-producers, a sales agent and additional funding.

Shivji has studied other animal-centric projects including Jerzy Skolimowski’s EO and Omar El Zohairy’s Feathers and plans on having multiple identical cows on the set to play Naserian. “The advantage I have is I’m working with a pastoralist community, the Maasai. Their entire livelihood is based on cattle,” he says.

The accidental filmmaker

Shivji is the son of a lawyer who was part of the Land Commission created in the 1990s to help the Maasai. Shivji has also hired a local “cultural steward [from] within the Maasai community who has been assigned to be a bridge between us and [them]”.

He stumbled onto filmmaking almost by accident. “I wanted to go to the University of Cape Town for journalism,” he says. “But I got into the film programme at York University in Toronto without realising I was applying for that. [It came with] a prestigious scholarship as I was one of only four African students to get in.”

That proved an offer too good to refuse even though Shivji admits he had never even watched African films, which are not available continent-wide but only on a regional level.

It was while in Canada that Shivji realised filmmaking was his calling. “The idea of being able to reach the masses, without language barriers and through a visual language which is universal, suddenly became very exciting for me,” Shivji says.

After graduating in Canada, he went back to Tanzania and started teaching at the University of Dar es Salaam while making films there as well.

Neorealism

The filmmaker says his films are rooted in the Third Cinema movement that developed in the 1960s in Africa and Latin America as a response to First and Second Cinema, namely Hollywood films and the work of European auteurs respectively.

“We’re making films for the people,” Shivji explains. “We’re going to break the rules intentionally because we don’t have the ability to use the studio setup, lighting, etc that exist in First and Second Cinema.”

The result is cinema which pays homage to neorealism - Shoeshine, indeed, shares the same title as Vittorio De Sica’s 1946 neorealist classic.

What began as frustration at the lack of infrastructure in the region developed, according to Shivji, into “a philosophical argument to tell stories from the ground up - [which means] a lot of shooting on location, being self-reflexive in the cinematography and using a non-professional cast”.

Much like Nigeria’s Nollywood, Tanzania’s grassroots filmmaking industry has short turnaround shoots, small budgets — under $10,000 — and dialogue-heavy stories.

Shivji, who was selected for the Berlinale Talents programme in 2014, says the lack of a film industry in Tanzania requires filmmakers to “wear all the hats and do a lot of guerrilla style independent filmmaking and even after that, we don’t have distribution channels”.

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

![[L-R]: Amanda Villavieja, Laia Casanovas, Yasmina Praderas](https://d1nslcd7m2225b.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/6/4/1/1471641_pxl_20251224_103354743_618426_crop.jpg)

No comments yet