It is exactly two years since Wild Bunch co-founder Vincent Maraval announced the spin-off of its international sales department, which he spearheaded over two decades, to create the independent standalone company Wild Bunch International (WBI).

Twenty-four months and one pandemic later, the company is beginning to unveil the fruits of its newfound independence.

Prior to Cannes, the company announced the creation of two companies, the French genre-focused production house Wild West and feature animation sales company Gebeka International.

Concurrently, the company’s core activity of international sales continues to turn at a frenetic pace.

The sales team led by Eva Diederix is out in force in Cannes selling 12 titles from across official selection and the parallel sections including Palme d’Or contenders Titane, Casablanca Beats, Nitram and Flag Day as well as a host of new projects by the likes of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, Arnaud Desplechin and Dario Argento.

The creation of Wild West and Gebeka International is just the beginning of an ambitious plan to create a “galaxy of companies” in France as well as other key European territories such as Spain, Italy and the UK, and Asia, focusing on local content with international sales or remake rights potential.

Screen sat down with Maraval for a catch-up about WBI’s progress to date.

There is some confusion in the market about the ongoing relationship between Wild Bunch International and Wild Bunch group. Can you explain?

We retain strong ties with Wild Bunch. It has a 20% stake in WBI, we’re the international distributor for its catalogue and we continue to work out of the same offices in Paris, but WBI is an entirely independent, autonomous company.

If Wild Bunch owns 20% of WBI, who owns the rest of the company?

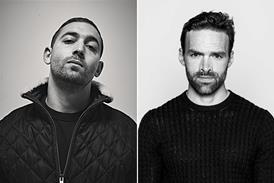

The employees own around 65%, with me and Brahim [Chioua, WBI co-head] holding the biggest stakes within that, and then a US partner holds the remaining shares.

What has changed in terms of the way you work or your ambitions with the creation of WBI?

There is no other sales company with the same global footprint as WBI in terms of acquiring and selling films around the world, bar perhaps The Match Factory. We’ve got everything from Italian genre to Asian animation to Romanian drama to US indie cinema.

We want to take this a step further to become even more involved as rights holders in local productions with international sales and remake potential. The platforms are diversifying more and more into local content. Our aim is to become a key partner for these platforms while continuing to cater to our long-time buyers.

How does the creation of Wild West and Gebeka International fit into this strategy?

The idea is to multiply our agreements with producers to create a kind of galaxy of production companies connected to Wild Bunch. We’ll produce locally in lots of countries to have a vast local offering that interests global actors.

We’ve already started doing this in France. With Brahim and Noëmie Devide, we created Getaway Film in 2019. Its first production was Alexandre Aja’s Oxygen for Netflix and it is now producing Michel Hazanavicius’s zombie comedy Final Cut [a remake of the 2017 cult Japanese hit One Cut Of The Dead].

The creation of Wild West with Thierry Lounas at Capricci is a project we have been working on quietly for five years, under the auspices of Capricci’s So Film Genre screenwriting residency that we have backed since the beginning.

On Gebeka International, it’s a sales company and is born out of our observation of the real evolution in the feature animation market in recent years and our feeling that we needed a separate entity to focus on these films.

On the production front, we have another three French companies in the works as well as accords coming together in Spain and Italy.

You didn’t mention the UK. Is it more difficult for you to work with the UK following Brexit?

Brexit will have absolutely no impact on the financing of films. We’ve recently co-produced Christian Carion’s My Son with Rebecca O’Brien at Sixteen Films which has just shot in Scotland with James McAvoy. We benefitted from the UK and French systems. It had no impact on the production of the film. Quite the contrary – I think today, a French-UK co-production is one of the combinations that make most sense. There’s nothing more virtuous.

Wild Bunch was one of the few European sales companies to make inroads into China. Does the country and wider Asia figure in your plans?

We’ve always been very present in China. The problem with China is how to repatriate the money. We had a very bad experience on Capernaum. The film made $68m but we haven’t been paid a penny. The distributor is hiding behind the Chinese state, saying he cannot get the money out. It’s not much good having an enormous success in China if you can’t get paid.

We’re trying to figure it out. One way could be to work with Chinese talent but in a neighbouring country. We have a project with Wild West that we’re thinking of locating in Indonesia. We’re working with CAA China to see if it would then be feasible to get Chinese talent to shoot there. This is something that happens all the time in Europe, so why not in Asia.

Can you tell us a bit more about the other production companies WBI is in the process of setting up?

I prefer not to announce any of them until they have in-house developed productions underway. In France, one will be focused on comedies and big TV series, which we’ve avoided up until now, while another will be involved in more urban subjects. We announced Wild West because we had a first slate of films to unveil, while with Gebeka we were able to announce its first sales acquisition Sheba.

The producers we’re working with are all very good artistically and great at development but don’t know the international scene and the routes to finance like us and are also scratching their heads over how to navigate the new world of the platforms – this is where we can come in.

Will WBI have exclusive sales rights to the films that are produced by these companies?

While we’re shareholders in these companies, they have their autonomy and are free to work with whoever makes most sense for their productions. If Pathé, Gaumont or FilmNation come along and are interested in the sales rights for a film, we would never say no if it made good business sense.

It was exactly the same when we were part of Wild Bunch. We never privileged the group’s distributors in Italy, Spain and Germany. In Italy, for example, we often worked with Lucky Red, even though Wild Bunch had shares in BIM. It was the same thing in France, where we worked a lot with Le Pacte, even though the group owned Wild Bunch Distribution.

During my time at Studiocanal, I saw the damage done by automatic distribution deals within a group. They cut out the desire that is necessary for a distributor to get behind a film.

How are you going to finance all the productions you are getting involved in?

In France, we’re using traditional sources of funding such as pre-sales to Canal+, regional film funding and tax incentives and then we will be looking to private equity to finance the gap.

We recently launched Wild West’s first slate of 12 genre projects at a special event in Bordeaux in June and we’re now close to signing a deal with a US equity partner to cover the gap for the whole slate.

Why would a US equity firm be interested in funding French-language genre films?

The US indie sector is now in the hands of the platforms, the indie sector has somehow become dependent. The producers, rights-holders have become employees and are no longer owners of their films.

This gap interests the international film financiers. They’ve lost the American market with fewer and fewer films getting made outside of the studios and the platforms.

Why not just simply bring in the platforms early on the projects you’re developing, like everyone else?

It’s important for us to maintain our independence. We decided that before a similar situation starts to take hold here, we needed to find different ways to finance our films so that we don’t have to tie them up with a single partner too early.

It doesn’t mean we’re against the platforms or don’t want to work with them, we just don’t want to be obliged to work with them early on in a project’s life. It’s all about independence and keeping control – which is why we have to be savvy about finance.

How did this strategy evolve?

In a way, the pandemic has helped. I know we’re all fed up with Zoom but there have been good sides. It has been beneficial for us because it has given us time to step back and reflect. When you’re tied up in the day to day business, you never have the time to do this.

Livia Van Der Staay, who joined WBI as a trainee and is now in charge of business development and oversees international distribution of our catalogues, has been instrumental. I asked her to take a look at the business plan and she quickly demonstrated an ability to understand the numbers and have a vision of the bigger picture.

Noëmie Devide, who has also risen through the ranks, has also been key to kickstarting our move into production, leading our first major production Oxygen for Netflix.

Eva Diederix who has completely taken over sales is also key. She’s mastered it completely. She’s great and full of energy. I’m terrible at delegating so being able to leave things to her has been a real comfort. Without these three people, I couldn’t have put in motion what we’re doing today. We would have remained a traditional sales company.

How do the arthouse directors that WBI has long and strong connections with – such as Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, Cristian Mungiu, Hirokazu Kor-eda – fit into your strategy?

The way we look after directors is almost akin to the role of a manager in the US. We’re not just there when they’re working on a film. Between two Gaspar Noé films, we look after Gaspar, between two Hirokazu Kor-eda films, we look after Kor-eda.

Cristian Mungiu can call me up and say, “I’ve got an idea for a film. How do you think I should do it?” It’s not simply a question of him coming to me and saying I need €800,000 against the international rights for the film.

If they want to make a film with Netflix or Amazon, then of course that’s their decision. The day they are obliged to make a film via a platform deal, it will mean we have failed.

No comments yet