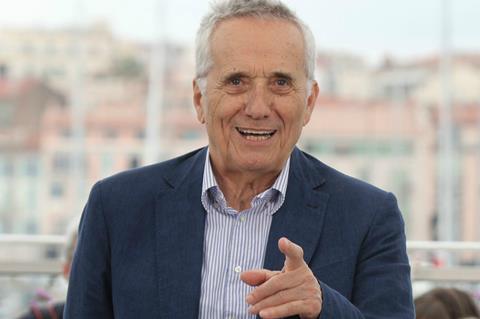

Now aged 80, Marco Bellocchio is showing no signs of slowing down. Screen talks to the veteran Italian director about his gangster epic The Traitor.

It is more than 50 years since the release of Marco Bellocchio’s wildly subversive debut feature Fists In The Pocket (1965), “a gleaming ice pick in the eye of bourgeois family values and Catholic morality, a truly unique work that continues to rank as one of the great achievements of Italian cinema,” as it was described recently by the Criterion Collection.

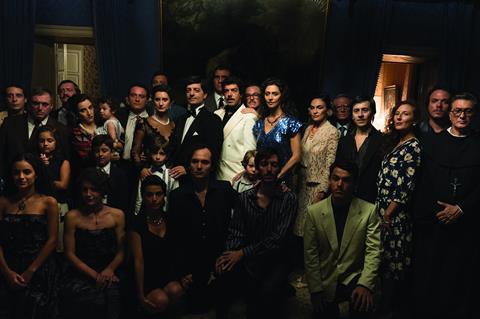

Now the Italian veteran has made his first full-blown Mafia epic, based on the true story of Cosa Nostra informer Tommaso Buscetta (Pierfrancesco Favino), whose testimony at the so-called Maxi trial (1986-1992) in Palermo was devastating to his former colleagues.

“When I shot Fists In The Pocket, I was 25. Now, I am almost 80 but the passion and my emotional link to all the stages of the [filmmaking] process is still there,” Bellocchio declares, speaking to Screen a month shy of his 80th birthday. “I couldn’t do it without passion. The level of energy might be slightly different… but I don’t need that rage which, once upon a time, was part of the fuel.”

Like many of Bellocchio’s films, The Traitor, which spans 20 years, holds up a mirror to recent Italian history. It has its moments of bloodcurdling violence but also works as a courtroom drama and as a multi-layered character study.

The project was suggested to Bellocchio by producer Beppe Caschetto. The veteran filmmaker began to read as much as he could about Buscetta’s colourful and controversial life.

“As I was researching in more depth, I found a more rounded character with different angles,” he says of the Mafia informer, regarded as a hero by some and utterly despised by others, including members of his own family.

“It was really important not to mythologise,” the director continues of his depiction of the turncoat gangster. Buscetta’s real significance wasn’t that he “named names” but that he revealed what Bellocchio calls the “architecture and the infrastructure” of the Cosa Nostra to Judge Giovanni Falcone (Fausto Russo Alesi). This gave Falcone the chance to bring the entire Mafia edifice tumbling down.

“It is absolutely clear the Mafia still exists but it is a completely different Mafia than the one that we see portrayed in the film,” Bellocchio says. “In a sense, the Maxi trial was the watershed. It was a partial victory on the side of the state.”

This, though, was a victory that came at a very high cost. Bellocchio shows the extreme retribution that the Mafia sought after being caught (literally in some cases) with its trousers round its ankles.

Released in Italy on the same day as the Cannes premiere, The Traitor has been a box-office hit, grossing more than $5m in its home country — and Bellocchio has been heartened by the film’s success in engaging younger Italian cinemagoers, many of whom weren’t aware of the history it chronicles.

The outcome is welcome news for the many partners behind The Traitor, most of them regular collaborators with the veteran director: Rai Cinema, Kavac Film (the outfit set up by Bellocchio and Francesca Calvelli in 1997), Ad Vitam Production, Match Factory Productions, IBC Movie and Gullane Entretenimento were all involved. The film was produced by Simone Gattoni (currently head of Kavac Film), Beppe Caschetto, Michael Weber, Viola Fügen, Caio Gullane, Fabiano Gullane and Alexandra Henochsberg.

Several writers contributed to the screenplay including Bellocchio himself, Ludovica Rampoldi, Valia Santella, Francesco Piccolo and Francesco La Licata, a journalist and author who has written several books and scripts on the Mafia.

Sony Pictures Classics took the film for Latin America, Scandinavia, Australia and New Zealand as well as for North America and will be releasing next January. The Match Factory handles international sales.

Ambitious intentions

Bellocchio is not the type to make small chamber pieces late in his career. The Traitor, one of his most ambitious efforts, was a huge endeavour with multiple locations (including several in Brazil), a big ensemble cast and several explosive set-pieces. It’s notable as the very first of the director’s films to use CGI. In one terrifying scene, we see characters being dangled out of helicopters in order to make them confess. There is also a ghoulishly spectacular explosion seen from the interior of the victims’ car.

As the arrests begin in earnest, we see thousands of rats being flushed out of a tenement. Bellocchio explains he had thought about showing “the enormous headlines” in the Italian press as the arrests were made but decided the images of verminous creatures fleeing a condemned building were stronger.

Bellocchio shows no signs of slowing down. His next project is his first TV drama series, and the subject matter is familiar. He will be revisiting the period of the kidnapping and murder of Italian politician Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades in 1978.

This was a period also covered in Bellocchio’s 2003 feature Good Morning, Night, and in an earlier documentary, Broken Dreams, but this time the drama will not be seen through the eyes of the prisoner or the terrorists but “everybody else around”.

Speaking to Bellocchio can be disconcerting. He belongs to an old tradition of European auteurist arthouse cinema and yet is now working in an era of streaming and digital effects.

He acknowledges the influence of post-war Italian directors like Federico Fellini and Roberto Rossellini. “But when you’re young, you are looking forwards,” he says. “It takes a certain maturity to be able really to appreciate the vastness, the greatness and the genius of these people.”

He was also friendly with Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Italian director and poet who was murdered in 1975. They knew each other through Laura Betti, the actress known as Pasolini’s muse but who later worked with Bellocchio.

“We came from different worlds,” he says of Pasolini. He was closer in temperament to contemporaries like Marco Ferreri (director of La Grande Bouffe), whom he considers to be very underrated, and to Michelangelo Antonioni. These are figures whose careers are long since over and are part of Italian cinema history. What is remarkable about Bellocchio is that he worked alongside them and yet is still at the centre of the Italian industry. He is still competing at the major festivals and is still on the Oscar hunt, today.

No comments yet