Charming performances carry Asgari’s fifth feature about a fictional director attempting to screen his latest film in Tehran

Dir: Ali Asgari. Iran/Italy/France/Germany/Turkey. 2025. 96mins.

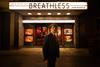

Cineliterate, meta-textual and wryly sarcastic, the latest film by Ali Asgari is a free-wheeling, sharp-witted satire that unpeels seemingly endless layers of Iranian cultural bureaucracy. A 40-year-old filmmaker, Bahram (director Bahram Ark, playing a fictionalised version of himself) has made a career crafting uncompromising Turkish-Azeri-language arthouse films, none of which have been shown in Iran. When his latest film is refused screening permission yet again, Bahram and his blue-haired producer Sadaf (Sadaf Asgari, also playing a version of herself) decide to organise a showing of it in defiance of the censor’s decision. Set in a single day, the picture’s droll tone and dry wit skewer the absurdity of the restrictions placed on life in Iran. Not all of it holds together but Asgari’s light touch and the likeable, naturalistic performances carry the picture.

Has a scrappy, off-the-cuff energy and an impish, defiant spirit

Divine Comedy is Asgari’s fifth feature, and marks a return to Venice – his debut, Disappearance, premiered at the festival in 2017. His second film, Until Tomorrow, launched in Berlin in 2022; his third, the vignette-based satire Terrestrial Verses, co-directed with Alireza Khatami, debuted in Cannes Un Certain Regard in 2023. Festival programmers are traditionally receptive to films about filmmaking and this, combined with Asgari’s international profile, should make a healthy festival run likely for the picture. And while the sheer volume of high-quality, boldly political work currently coming out of Iran makes for a crowded market, Divine Comedy’s astringent humour could make it attractive to arthouse distributors or streaming platforms.

The picture’s sardonically amused tone and breezy jazz score may feel irreverent, even flippant, but Asgari digs into serious subjects: the obstacles to creating art and the regime’s heavy-handed interference in all aspects of life. Its cast list alone is a political statement. Sadaf Asgari, the director’s niece and the magnetic star of all but one of Asgari’s feature films has been banned from acting in Iran after she attended Cannes with Terrestrial Verses. The doors that are closed in her character’s face because of her blue hair and refusal to wear a hijab have a symbolic resonance. In real life, Bahram Ark, along with his twin brother Bahman, who also appears in the film, are filmmakers (they made Soyoogh in 2016 and Skin in 2020) who have themselves faced government censorship.

Here, the brothers play fictional versions of themselves. Following an early collaboration together, Bahram has stuck to his guns, crafting weighty art cinema; Bahman still displays a Godard poster on the wall of his moneyed apartment but has sold out creatively, making regime-approved populist comedies with titles like ’Women Are Amazing’, and ’The Fox of Valentine 2’. Gallingly for Bahram, his most popular film is his first, which he directed with his brother. An exuberant cinema owner praises the film’s “long takes”. Disgruntled, Bahman argues that they used such shots because they didn’t know anything about filmmaking.

Accordingly, long takes and locked shots figure prominently in Divine Comedy, but in this case there’s a reason beyond inexperience: Asgari uses the static compositions to evoke the rigidity of the regime and the oppressive control that it exerts. This is contrasted with the fluid freedom of the sequences in which Bahman and Sadaf zoom around Tehran on her sorbet-pink Vespa (there’s perhaps a nod here to another loosely autobiographical film about a filmmaker, Nanni Moretti’s Dear Diary).

Over the course of the day, Bahram has heated discussions on everything from The Matrix to Kiarostami. He and Sadaf tiptoe around the ego of a coked-up actor Rouzbeh (Hossein Soleimani) and Bahram is summoned for a meeting with Haranov (Mohammad Soori), a man with an expensive suit, big promises and a viper’s smile, who claims to be “a friend who wants to help”. Less successful is a random street encounter with a man who describes himself as a prophet, who offers to release Bahram from purgatory then steals one of his doughnuts. Elsewhere, a special mention must go to the film’s canine supporting actor, who is credited, entirely correctly, as Shila The Lovely Dog.

Ultimately, like the screening that Bahram and Sadaf attempt to hustle together, the picture has a scrappy, off-the-cuff energy and an impish, defiant spirit. It makes a persuasive case that art – and laughter – are potent weapons in the struggle against oppression.

Production companies: Seven Springs Pictures, Taat Films

International sales: Goodfellas, Flavien Eripret, feripret@goodfellas.film

Producers: Milad Khosravi, Ali Asgari

Screenplay: Alireza Khatami, Bahram Ark, Bahman Ark, Ali Asgari

Cinematography: Amin Jafari

Editing: Ehsan Vaseghi

Production design: Melika Gholami

Music: Hossein Mirzagholi

Main cast: Bahram Ark, Sadaf Asgari, Bahman Ark, Hossein Soleimani, Mohammad Soori, Amirreza Ranjbaran, Faezeh Rad, Milad Ashkali, Amirreza Ranjbaran, Shahoo Rostami